“We want the reversal of these laws,” says Vishavjot Grewal, who is protesting at Singhu on the Haryana-Delhi border. “We are very attached to our land and we cannot tolerate anyone taking it away from us,” adds the 23-year-old from a family of farmers, who has helped organise protests in Pamal, her village in Ludhiana district, since the three laws were passed in Parliament last September.

The women in her family, like at least 65 per cent of women in rural India (notes Census 2011), are engaged directly or indirectly in farming activities. Not many of them own land, but they are central to farming, where they do most of the work – sowing, transplantation, harvesting, threshing, crop transportation from field to home, food processing, dairying, and more.

Still, on January 11, when the Supreme Court of India passed an order putting the three farm laws on hold, the Chief Justice also reportedly said that women and the elderly must be ‘persuaded’ to go back from the protest sites. But the fallout of these laws concerns and impacts women (and the elderly) too.

The laws the farmers are protesting against are the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020 ; the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act , 2020; and the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020 . The laws have also been criticised as affecting every Indian as they disable the right to legal recourse of all citizens, undermining Article 32 of the Constitution of India.

The laws were first passed as ordinances on June 5, 2020, then introduced as farm bills in Parliament on September 14 and rushed through as Acts on the 20th of that month. The farmers see this legislation as devastating for their livelihoods by expanding the space for large corporate to exercise even greater power over farming. They also undermine the main forms of support to the cultivator, including the minimum support price (MSP), the agricultural produce marketing committees (APMCs), state procurement and more.

“Women are going to be the worst sufferers of the new farm laws. Though very much involved in agriculture, they do not have decision-making powers. The changes in the Essential Commodities Act [for example] will create a lack of food and women will face the brunt of it,” says Mariam Dhawale, general secretary, All India Democratic Women's Association.

And many of these women – young and old – are present and resolute at the farmers protest sites in and around Delhi, while many others who are not farmers, have been coming there to register their support. And many are also there to sell some items, earn a day’s wages, or just eat the plentiful meals offered at the langars .

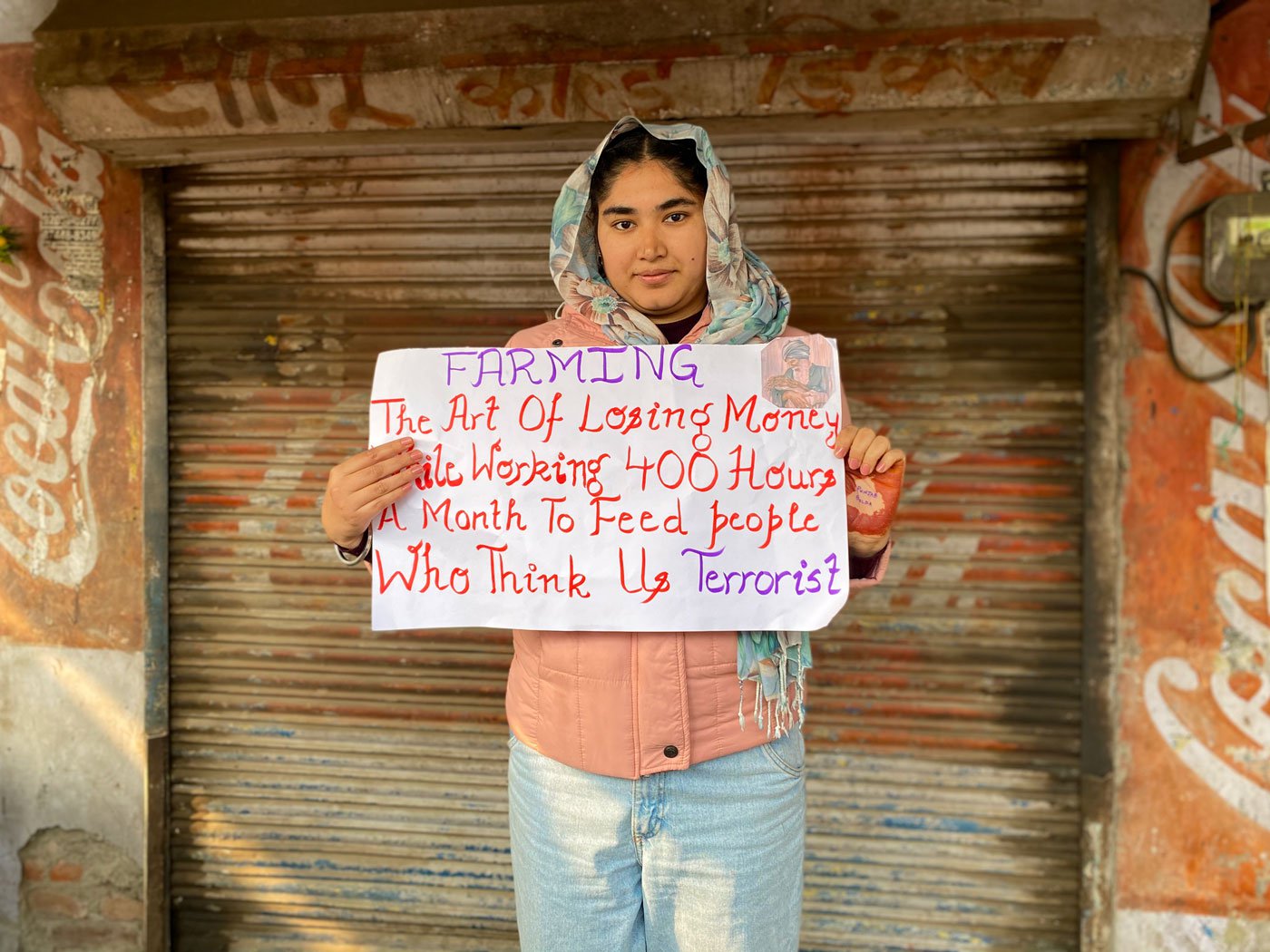

Bimla Devi (in red shawls), 62, reached the Singhu border on December 20 to tell the media that her brothers and sons protesting there are not terrorists. Her family cultivates wheat,

jowar

and sugarcane on the family’s two acres in Sehri village in Kharkhoda block of Haryana’s Sonipat district. “We heard on TV our sons being called goons. They are farmers not terrorists. I started crying seeing how the media was talking about my sons. You will not find more big-hearted people than farmers,” says Bimla Devi, whose 60-year-old sister, Savitri (in blue), is with her at Singhu.

“I am here to fight for my rights, for my future,” says Aalamjeet Kaur, 14 years old and a Class 9 student. She is at the Singhu protest site with her younger sister, grandmother and her parents. They have all come from Pipli village in Punjab’s Faridkot block, where her mother works as a nurse and her father as a school teacher. The family also cultivates wheat and paddy on their seven-acre farmland. “I have been helping my parents with farming since I was very little," says Aalamjeet. "They educated me on the rights of us farmers and we will not go back until we get our rights back. This time we farmers will win.”

Vishavjot Grewal’s family owns 30 acres of land in Pamal village of Ludhiana district, where they mainly cultivate wheat, paddy and potatoes. “We want the reversal of these [farm] laws,” says the 23-year-old, who came with relatives to Singhu in a mini-van on December 22. “We are very attached to our land and we cannot tolerate anyone taking it away from us. In our Constitution it is written that we have the right to protest. This is a very peaceful protest. From langar to medical aid, everything is provided here.”

“I have come here to support my farmers. But these laws will harm each and every person, though people think that the laws will affect only farmers,” says Mani Gill, 28, from Kot Kapura village in Faridkot tehsil of Punjab’s Faridkot district. Mani has an MBA degree and works in the corporate sector. “I am sure we will win,” she adds. “It’s beautiful to see that a mini-Punjab has been created in Delhi. You will find people from all the villages of Punjab here.” Mani is a volunteer with a youth-run platform that helps create awareness about farmers’ issues on social media. “Apart from the three new farm laws, we also try to talk about other major problems of farmers and what could be the solutions. We try to bring forward issues that farmers face every day,” she says. Mani’s parents could not come to Singhu, but, she says, “I feel they too are equally doing important tasks. Because we are here, they are left doing double work [back in the village], taking care of our animals and our farmland.”

Sajahmeet (right) and Gurleen (full names not provided) have been participating at different farmers’ protest sites since December 15. “It was very difficult to remain at home knowing that they needed more people at the protests,” says 28-year-old Sahajmeet, who came here from Patiala city in Punjab by taking lifts in various cars and tempos. For a while, she was at the Tikri protest site in West Delhi, volunteering in community kitchens. “We go wherever the help is required,” she adds.

For women at the protest, she points out, toilets are a problem. “The portable toilets and those at the [petrol] stations are quite dirty. Also, they are far from where women are staying [in tents and tractor-trolleys across the site]. Since we are comparatively fewer in numbers, the safest option is to use the washrooms closest to where we are staying,” says Sahajmeet, a PhD English Literature student at Punjabi University in Patiala. “While trying to use a washroom, I was told by an older man: ‘Why have women come here? This protest is the work of men’. It feels unsafe at times [at night] but seeing other women here makes us feel stronger together.”

Her friend, 22-year-old Gurleen, from Meekey village in Gurdaspur district’s Batala tehsil , where her family cultivates wheat and paddy on two acres, says, “The cost of my entire education was covered by farming. My household depends on agriculture. My future and only hope is agriculture. I know it can provide me with both food and security. Education has made me see how these different government policies will affect us, especially women so it is important to protest and stand in solidarity.”

Harsh Kaur (extreme right) has come to the Singhu border from Punjab’s Ludhiana’s city, some 300 kilometres away. The 20-year-old had contacted a youth organisation to volunteer at their free medical camp at the protest site, along with her sister. The medical aid tent has trained nurses who advise the volunteers on distributing medicines. Harsh, a student of BA in Journalism, says, “The government is pretending that these laws are good for farmers, but they are not. The farmers are the ones who sow, they know what is good for them. The laws only favour the corporates. The government is exploiting us, if not, they would have given us an assurance of MSP [minimum support price] in writing. We cannot trust our government.”

Laila (full name unavailable) sells tool-sets at Singhu that include a plier, electric lighter and two types of screwdrivers. Each set costs Rs. 100. She also sells three pairs of socks for the same price. Laila picks these items once a week from Sadar Bazar in North Delhi; her husband is a vendor too. She is here with her sons Michael(purple jacket), 9, and Vijay(blue jacket), 5, and says, “We have come to this gathering just to sell these items. Since this [protest] has started we come here from 9 in the morning to 6 in the evening, and sell 10-15 sets every day.”

“I have no farmer in my family. I fill up my stomach selling this stuff,” says Gulabiya, 35, a street vendor who lives in Singhu, where the protest site is teeming with hawkers trading various items. Gulabiya

(full name unavailable)

sells small musical drums, hoping to earn Rs. 100 for each. Her two sons work as labourers. “I make 100-200 rupees [a day],” she says. “No one buys these drums for 100 rupees, they all bargain, so I have to sell for 50 and sometimes even 40 rupees.”

“I have come here to eat roti,” says Kavita (full name unavailable) , a waste-worker from North Delhi’s Narela locality. She has been coming to the Singhu border to pick up discarded plastic bottles. At the end of the day, Kavita, who is around 60, sells these and other waste items collected from the protest site for Rs. 50-Rs. 100 to a scrap dealer in her locality. “But some people here shout at me,” she says. “They ask me why I have come here?”

“It was very difficult for me to participate in the protest because my parents were not in favour of me coming here. But I came because farmers need support from youth,” says 24-year-old Komalpreet (full name not provided) from Kot Kapura village in Faridkot tehsil of Punjab’s Faridkot district. She came to the Singhu border on December 24, and volunteers with a youth-run platform that helps raise awareness about farmers’ issues on social media. “We are recreating history here,” she adds. “People are here regardless of their caste, class and culture. Our gurus have taught us to fight for what is right and stand with those being exploited.”