Marking the border between two countries carved out of one by the bloody Partition of 1947, the Radcliffe Line also splits Punjab into two halves. Along with its geography, the line, named after the British lawyer who served as chairman of the boundary commissions, also divides two scripts of the Punjabi language. “Partition left a fresh wound forever to the literature and two scripts of the Punjabi language,” said Kirpal Singh Pannu from the village Katahri in Payal tehsil of the state’s Ludhiana district.

Pannu is a 90-year-old former soldier who has dedicated three decades of his life to applying salve to this particular wound of Partition. A retired deputy commandant in the Border Security Force (BSF), Pannu has transliterated scriptures and holy books such as the Guru Granth Sahib, the Mahan Kosh (one of the most revered encyclopaedias of Punjab) and other literary works from Gurmukhi to Shahmukhi and the other way around.

Shahmukhi, written from right to left like Urdu, has not been used in Indian Punjab since 1947. In 1995-1996, Pannu developed a

computer programme

that converted the Guru Granth Sahib from Gurmukhi to Shahmukhi and vice versa.

Pre-partition, Urdu-speakers would also be able to read Punjabi written in Shahmukhi. Before the formation of Pakistan, most literary works and official court documents were in Shahmukhi. Even

Qissa,

the traditional storytelling art form of the erstwhile undivided province, used only Shahmukhi.

Gurmukhi, written from left to right and bearing some resemblance to the Devanagari script, is not used in Pakistan’s Punjab. As a result, later generations of Punjabi-speaking Pakistanis, unable to read Gurmukhi, remained alienated from their literature. They could read the great literary works of undivided Punjab only when these were produced in the script they knew, Shahmukhi.

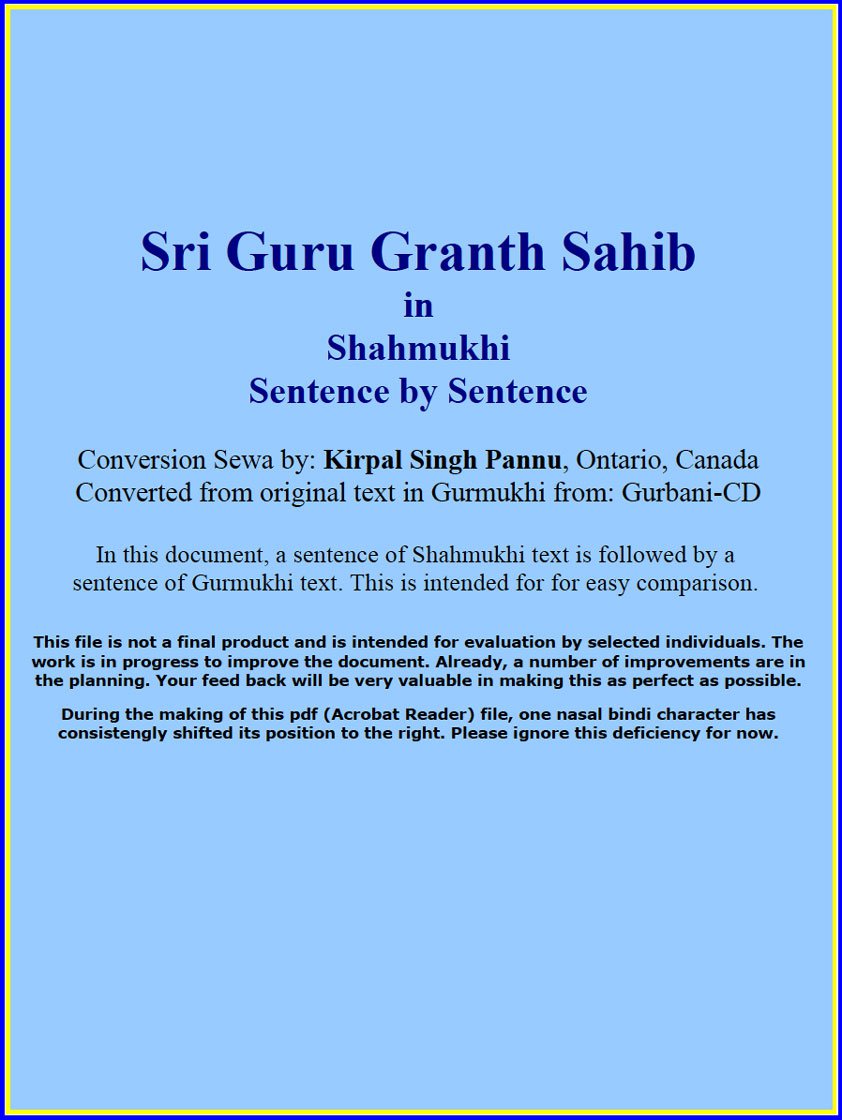

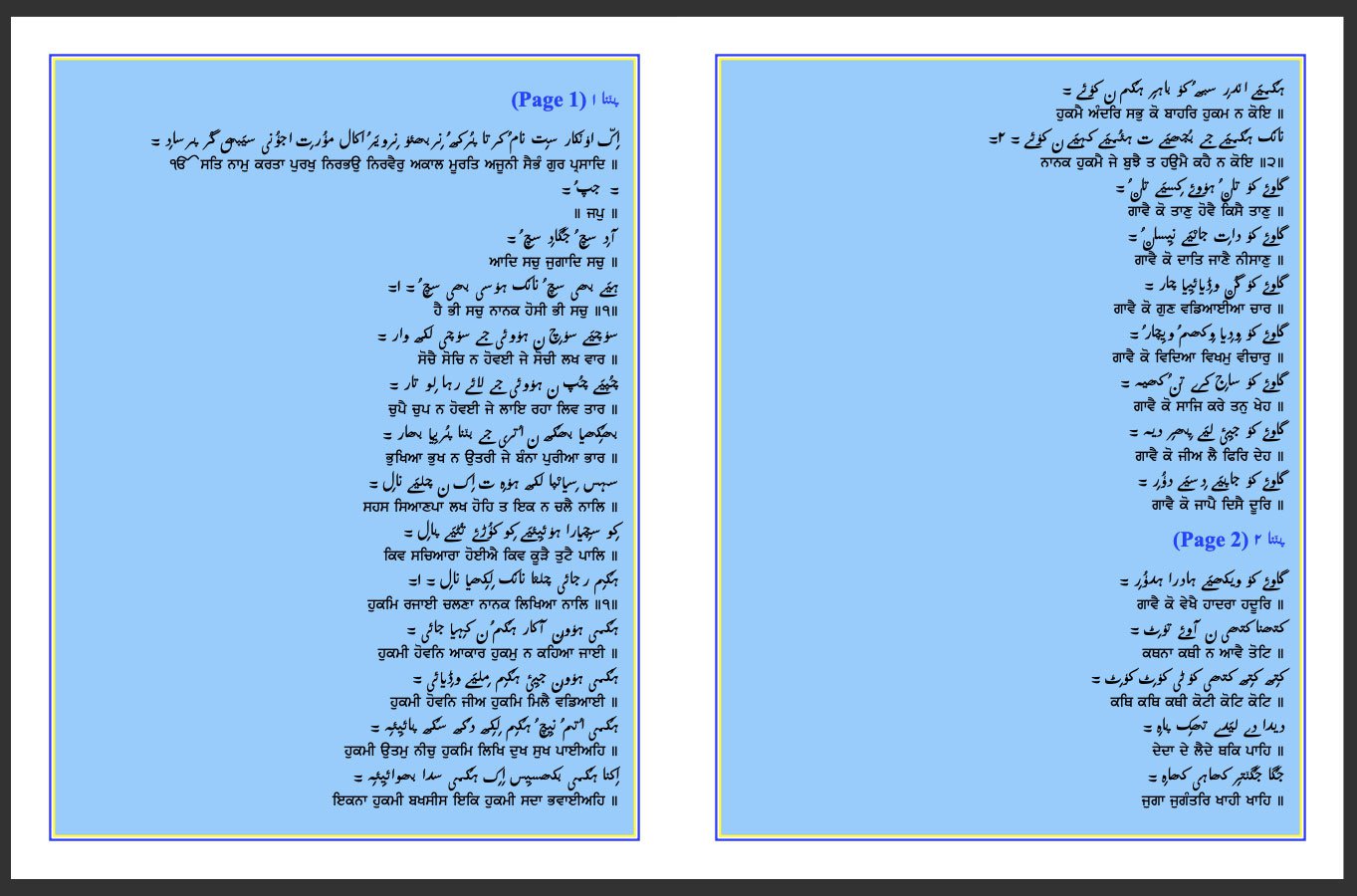

Left: Shri Guru Granth Sahib in Shahmukhi and Gurmukhi. Right: Kirpal Singh Pannu giving a lecture at Punjabi University, Patiala

Dr. Bhoj Raj, 68, a language expert and a French teacher based in Patiala, reads Shahmukhi too. “Before 1947, Shahmukhi and Gurmukhi were both in use, but Gurmukhi was mostly restricted to gurdwaras (Sikh places of worship),” he said. According to Raj, in pre-Independence years, students taking Punjabi language examinations were expected to write in Shahmukhi.

“Even the Hindu religious texts such as Ramayana and Mahabharata were written in Perso-Arabic script,” Raj said. As Punjab was divided, the language cleaved too, Shahmukhi migrated to Western Punjab, became Pakistani, and Gurmukhi resided alone in India.

Pannu’s project came as a way to allay a decade-long anxiety over the loss of a key component of Punjabi culture, language, literature and history.

“The writers and poets from eastern Punjab (Indian side) wanted their creations to be read in western Punjab (Pakistani side) and vice versa,” Pannu said. At literary gatherings he would attend in Toronto, Canada, Pakistani Punjabis and Punjabis of other nationalities would lament the loss.

At one such meeting, readers and scholars expressed the urge to read one another’s literature. “That would have been possible only if both sides learnt both the scripts,” said Pannu. “That was, however, easier said than done.”

The only way to resolve the situation was to transliterate major literary works into the script in which they were unavailable. For Pannu, an idea was born.

Eventually, Pannu’s computer programme would enable a reader from Pakistan to access and read the Guru Granth Sahib, the sacred book of Sikhism, in Shahmukhi. The same programme would also transliterate books and texts from Pakistan available in Urdu or Shahmukhi to Gurmukhi.

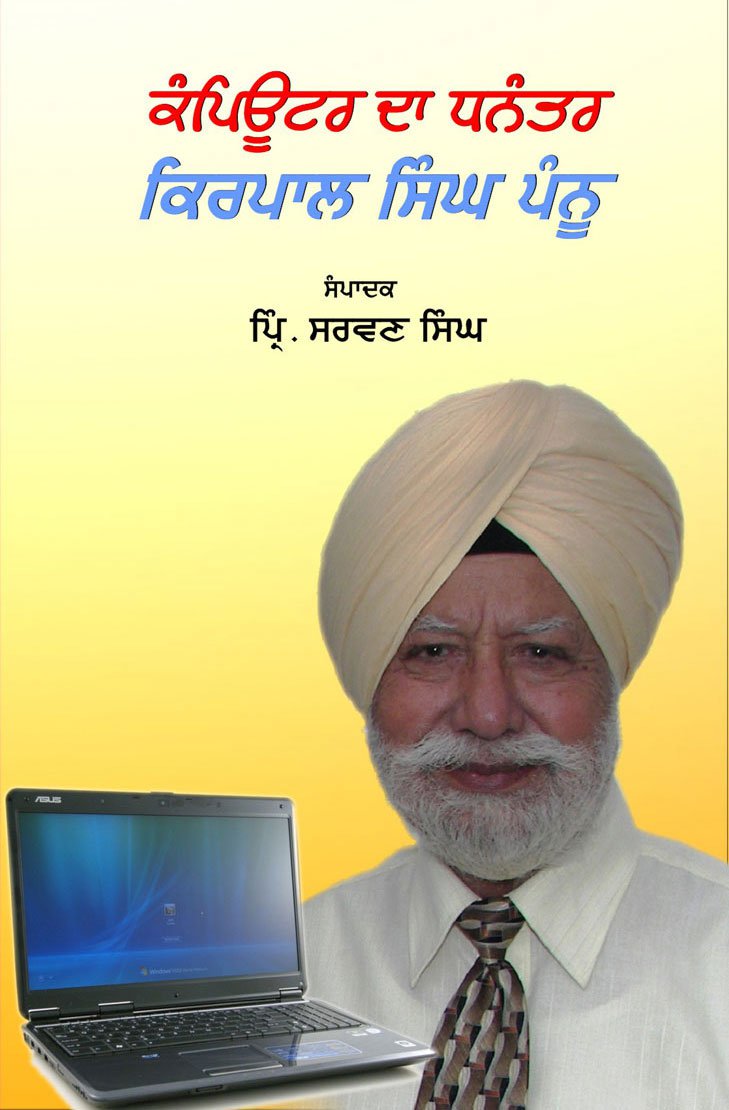

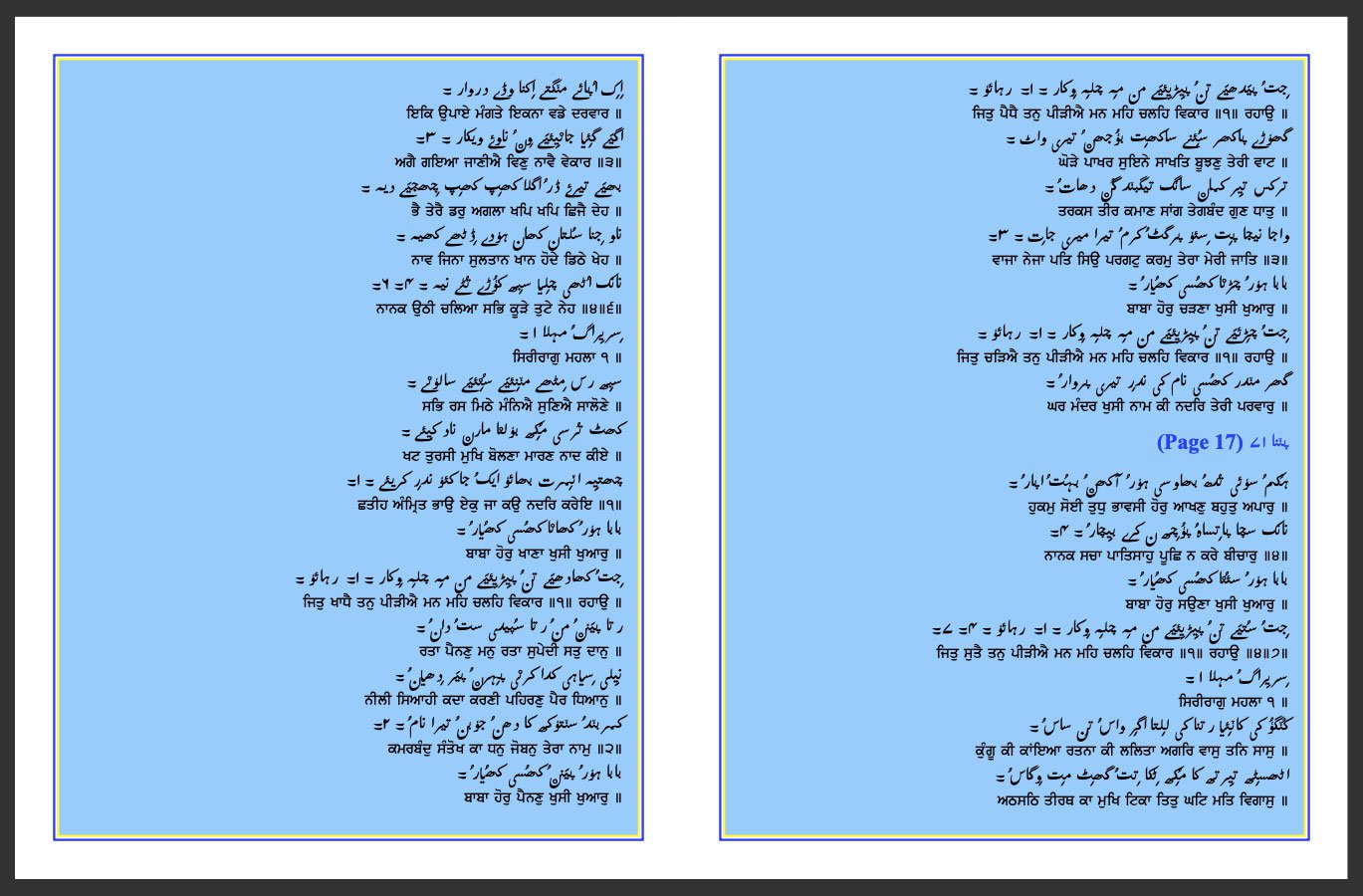

Pages of the Shri Guru Granth Sahib in Shahmukhi and Gurmukhi

*****

After his retirement in 1988, Pannu went to Canada and there, he studied how to use a computer.

A significant population in Canada, Punjabis there were keen to read news from their homeland. Punjabi dailies such as

Ajit

and

Punjabi Tribune

were sent from India to Canada by air.

Cuttings from these and other newspapers would then be used to produce other newspapers in Toronto, Pannu said. As these newspapers were almost like a collage of cuttings from different publications, they carried multiple fonts.

One such daily was

Hamdard Weekly

, where Pannu would later work. In 1993, its editors decided to produce their newspaper in a single font.

“Fonts had started coming in, and the use of computers was now possible. The first conversion I started was from one font of Gurmukhi to another one,” Pannu said.

The first typed copy of

Hamdard Weekly

, in Anantapur font, was released from his residence in Toronto in the early nineties. Then, at a meeting of the

Punjabi Kalman Da Kafla

(Punjabi Writers’ Association), an organisation of Punjabi writers in Toronto, started in 1992, members decided that the Gurmukhi-Shahmukhi conversion was necessary.

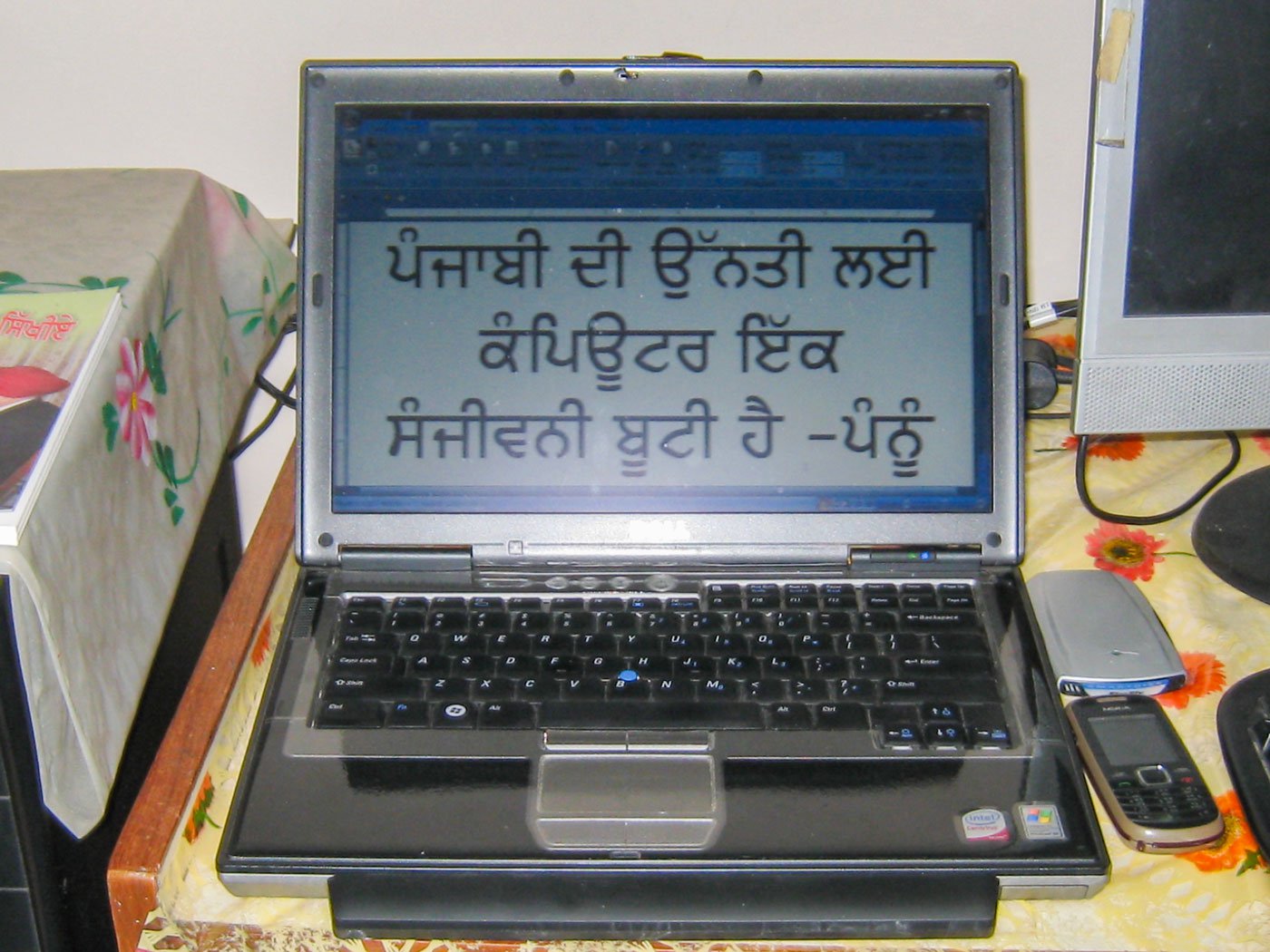

Left: The Punjabi script as seen on a computer in January 2011. Right: Kirpal Singh Pannu honoured by Punjabi Press Club of Canada for services to Punjabi press in creating Gurmukhi fonts. The font conversion programmes helped make way for a Punjabi Technical Dictionary on the computer

Pannu was among the few who could comfortably use computers, and was given the responsibility of achieving this result. In 1996, the Academy of Punjab in North America or APNA Sanstha, another organisation dedicated to Punjabi literature, held a conference where Navtej Bharati, one of the most well-known Punjabi poets, announced: “Kirpal Singh Pannu is designing a programme. Ki tussi ik click karoge Gurmukhi ton Shahmukhi ho jauga, ik click karoge te Shahmukhi ton Gurmukhi ho jauga [You can convert text from Shahmukhi to Gurmukhi and vice versa with just one click]."

Initially, he felt he was shooting in the dark, the soldier said. But after some early technical difficulties, he was able to make progress.

“Excitedly, I went to show it to Javed Boota, a literary figure who knew Urdu and Shahmukhi,” he said.

Boota pointed out that the font Pannu had used for Shahmukhi was flat, like a series of concrete blocks in a wall. He told Pannu it was something like Kufi (a font in which Arabic was rendered)

,

which no Urdu reader would accept, and that it was the Nastaliq font, with the appearance of leafless twigs on a dried tree, that is accepted in Urdu and Shahmukhi.

Pannu returned, disappointed. Later, his sons and friends of his sons helped him. He consulted experts and visited libraries. Boota and his family also helped. Eventually, Pannu found the font Noori Nastaleeq.

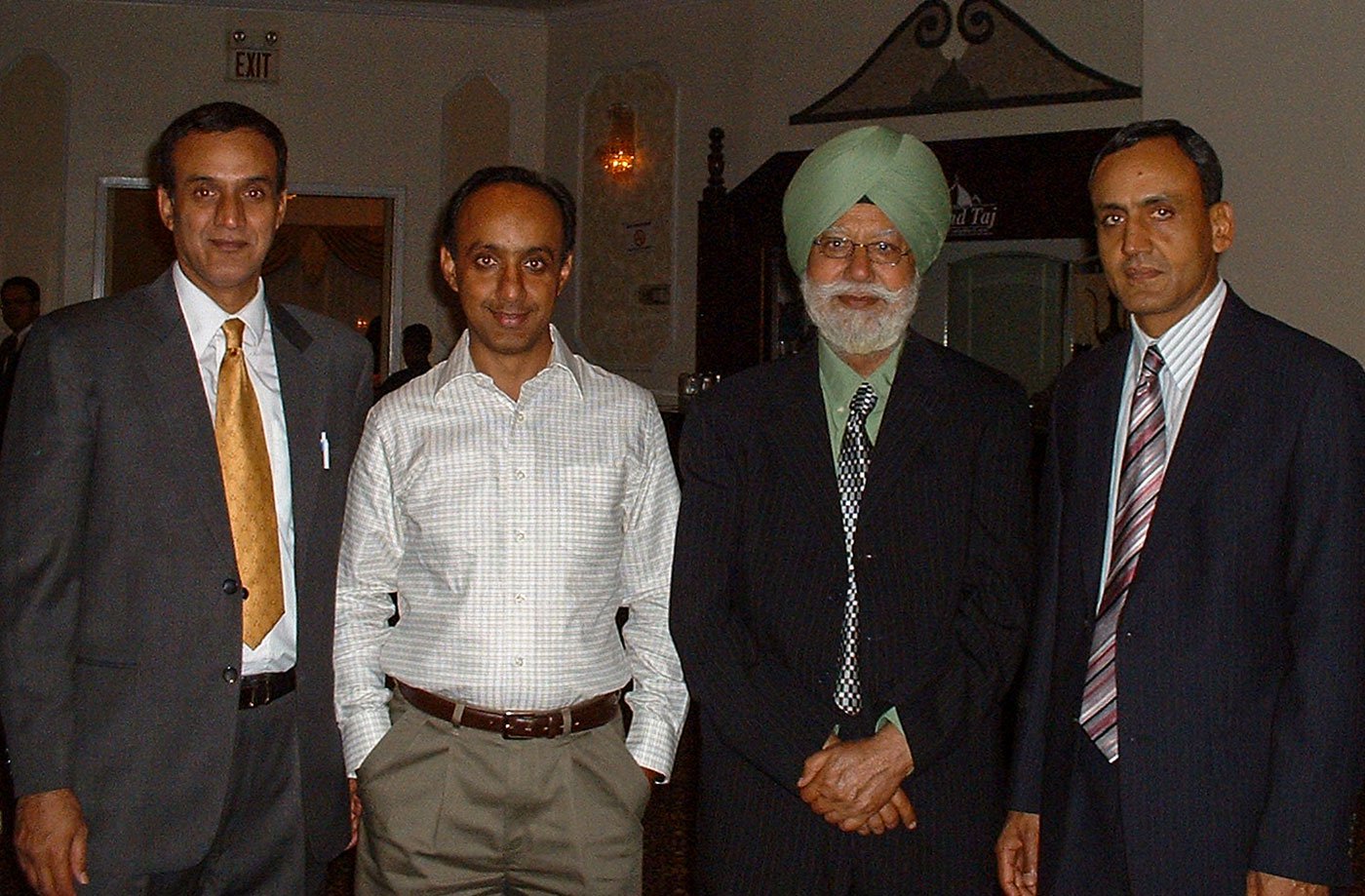

Left: Pannu with his sons, roughly 20 years ago. The elder son (striped tie), Narwantpal Singh Pannu is an electrical engineer; Rajwantpal Singh Pannu (yellow tie), is the second son and a computer programmer; Harwantpal Singh Pannu, is the youngest and also a computer engineer. Right: At the presentation of a keyboard in 2005 to prominent Punjabi Sufi singer

By now, he had gained a significant knowledge of fonts, and was able to mould Noori Nastaleeq according to his needs. “I had prepared it parallel to Gurmukhi. Therefore, another major problem remained. We had to still bring it to the right so it could be written from right to left. So, like one pulls an animal tied to rope and a pole, I would pull each letter from left to right,” Pannu said.

Transliteration requires a matching pronunciation in the source and the target scripts, but each of these scripts had some sounds without an equivalent letter in the other. One example was the Shahmukhi letter

noon

ن — which performs the function of a silent nasal sound and is absent in Gurmukhi. For each such sound, Pannu created a new letter by adding elements to an existing letter.

Pannu can now work in Gurmukhi in over 30 fonts and he has three or four fonts for Shahmukhi.

*****

Pannu belongs to a family of farmers. The family own 10 acres of land in Katahri; Pannu’s three sons are all engineers and live in Canada.

In 1958, he joined the armed police of the erstwhile state of Patiala and East Punjab States Union (PEPSU), a union of former princely states in the region. He joined as a senior grade constable at Qila Bahadurgarh, Patiala. During the 1962 war, Pannu was posted as head constable in Dera Baba Nanak, Gurdaspur. At the time, it was the Punjab Armed Police (PAP) that guarded the Radcliffe Line.

In 1965, the PAP merged into the BSF and he was posted in Lahaul and Spiti, then part of Punjab. He worked on the BSF’s bridge construction work with the Public Works Department, later being promoted to Sub-Inspector and rising to Assistant Commandant of the BSF.

Left: Pannu in uniform in picture taken at Kalyani in West Bengal, in 1984. He retired as Deputy Commandant in 1988 from Gurdaspur, Punjab, serving largely in the Border Security Force (BSF) in Jammu and Kashmir . With his wife, Patwant (right) in 2009

He says his love for literature and poetry stems from his freedom of thought and from his life at the borders where he missed home. He recited a couplet he wrote for his wife:

“Pal bhi saha na jaaye re teri judai ae sach ai

Par idda judaaiyan vich hi ye beet jaani hai zindagi.

[Not a moment goes by when I don’t die longing for you

Longing became my destiny — eternal, Allahu!]

”

Posted in Khem Karan as company commandant of the BSF, he and his Pakistani counterpart, Iqbal Khan, had set a custom. “In those days, people from both sides of the boundary would visit the border. It was on me to offer the Pakistani guests tea and he would ensure that Indian guests never went without having tea from him. A few cups of tea would sweeten the tongue and soften the heart,” he said.

Pannu eventually showed his Gurmukhi-to-Shahmukhi script conversion to Dr. Kulbir Singh Thind, a neurologist who is dedicated to Punjabi literature and who later uploaded

Pannu’s transliteration

on his website,

Sri Granth Dot Org

. “It was present there for many years,” Pannu said.

In 2000, Dr. Gurbachan Singh used Persian letters in the Arabic version of the Sri Guru Granth Sahib. While doing so, he used the programme designed by Pannu.

Left: The cover page of Computran Da Dhanantar (Expert on Computers) by Kirpal Singh Pannu, edited by Sarvan Singh. Right: More pages of the Shri Guru Granth Sahib in both scripts

Pannu then worked on transliterating the Mahan Kosh, one of the most revered encyclopaedias of Punjab, compiled by Bhai Kahn Singh Nabha over 14 years, mainly written in Gurmukhi.

He also went on to transliterate

Heer Waris Ke Sheron Ka Hawala

, a 1,000-page book of poetry, into Gurmukhi.

Saba Chaudhry, 27, a reporter from Pakistan’s Shakargarh

tehsil

that was part of India’s Gurdaspur district before 1947, said the newer generation in the region barely knows Punjabi, as it is advised to speak Urdu in Pakistan. “Punjabi is not taught in school courses,” she said. “People here don’t know Gurmukhi, neither do I. Only our past generations were familiar with it.”

The journey was not always exhilarating. In 2013, a computer science professor laid claim to the transliteration work as his own, leading Pannu to write a book refuting his claims. He faced a defamation suit; the decision is pending in a court of appeals after the lower judiciary ruled in Pannu’s favour.

Pannu has reason to be pleased with the outcome of his years of work to soften one of Partition’s harsh blows. The sun and the moon of the Punjabi language, the two scripts, continue to shine across the borders. Kirpal Singh Pannu is a hero for a common language of love and longing.