“It is no longer like it used to be years ago. Today’s women are aware and well-informed about the contraceptive methods that are available,” says Salah Khatun, standing in a sunlit verandah of a small brick-and-mortar house, its walls painted sea-green.

She is speaking from experience – over the last decade, Salah, along with her nephew’s wife Shama Parveen, have become the unofficially designated family planning and menstrual hygiene advisors for the women of Hasanpur village in Bihar’s Madhubani district.

Women often approach them with questions and requests about contraception, how they can maintain a gap before the next pregnancy, about immunisation rounds and more. And some also come seeking an injectable hormonal contraceptive, surreptitiously if need be.

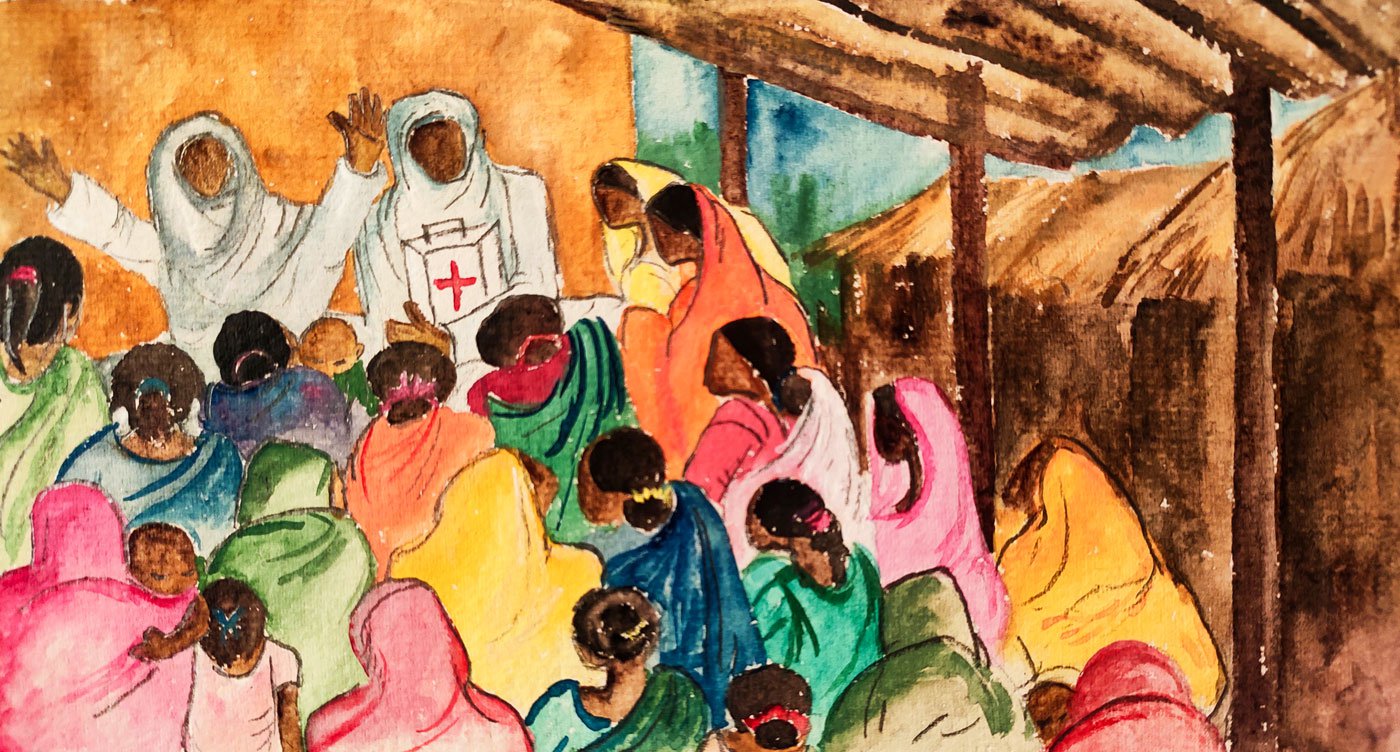

In the privacy of a little clinic, in a corner room of Shama’s house, with little vials and blister-packed strips of medication sitting on shelves, Shama, who is in her early 40s, and Salah, who is in her early 50s, neither of them a trained nurse, administer the intra-muscular injection. “Sometimes women come in alone, take the injection and leave quickly. Nobody at their home needs to know anything,” says Salah. “Others come in with their husbands or women relatives.”

This is a dramatic change from even a decade ago, when family planning techniques were barely used by the residents of Hasanpur, a village of roughly 2,500 residents in Saini gram panchayat of Phulparas block.

What brought about the change? “ Yeh andar ki baat hai [That’s an inside story],” Shama says.

In the privacy of a little home-clinic, Salah Khatun (left) and Shama Parveen administer the intra-muscular injection

Hasanpur’s low contraception use of the past points to a state-wide situation – NFHS-4 (2015-16) notes that Bihar had a total fertility rate of 3.4 – significantly higher than the all-India number of 2.2. (The TFR is the number of children on average that a woman will bear during her childbearing years.)

The state’s TFR dropped to 3 in NFHS-5 (2019-20 ), and the decline coincides with a growth in use of contraception in the state between rounds 4 and 5 of the National Family Health Survey – from 24.1 per cent to 55.8 per cent.

Tubal ligation – the sterilisation procedure for women – continued to be the dominant mode of family planning, accounting for 86 per cent of all modern methods (notes NFHS-4). Detailed data on this for NFHS-5 is awaited, but a push for newer methods of ensuring gaps between children, including the injectable contraceptive, is now a key element of state policy.

In Hasanpur too, as Salah and Shama observe, more women are seeking out contraception – mainly pills, but also the hormonal injection, called depot-medroxy progesterone acetate (DMPA), marketed in India as ‘Depo-Provera’ and ‘Pari’. Government dispensaries and primary health centres offer DMPA under the brand name ‘Antara’. Until its launch in India in 2017, ‘Depo’ was usually imported into Bihar from neighbouring Nepal by individuals and private organisations, including non-profit groups. The price ranges from Rs. 245 to 350 per injection, except at government-run healthcare centres and hospitals, where it is free.

The injectable is not without its detractors, and was resisted for years, especially in the 1990s, by women’s rights groups and health activists amid concerns of side effects ranging from dysmenorrhea (excessive or painful bleeding) to amenorrhea (absence of bleeding), acne, weight gain, weight loss, menstrual irregularities and more. The long protests over its safety, a series of trials, feedback from various groups and other processes led to DMPA not being launched in India until 2017. It is now indigenously manufactured.

The injectable was launched as Antara in October 2017 in Bihar, and by June 2019 it was available at all urban and rural primary health centres and sub-centres. According to the state government’s data, 424,427 doses were administered by August 2019, the highest in the country. As many as 48.8 per cent of women who took it once had also received a second dose.

Hasanpur’s women trust Shama and Salah, who say most of them now ensure a break after two children. But this change took time

There are concerns with using DMPA for longer than two years. Among the risks that have been studied are loss of bone mineral density (believed to be reversible on discontinuation of the injectable). The World Health Organizaton has recommended that women using DMPA may be reviewed every two years.

Shama and Salah insist they are very particular about safety. Hypertensive women are not prescribed the injectable contraceptive, and the two healthcare volunteers make sure blood pressure is checked at every instance before the injection is administered. They add that they have received no complaints of side effects.

They don’t have data on how many women in the village are using Depo-provera, but it is evidently a popular choice, perhaps because it offers confidentiality and a one-jab option every three months. And women who are married to men returning home from the cities only for a few months of the year find it a simple method to use for short periods of time. (Healthcare workers and medical papers say that fertility returns a few months after the lapse of three months since the last dose.)

Another reason for the hormonal injection’s growing acceptance in Madhubani is the work done here by the Ghoghardiha Prakhand Swarajya Vikas Sangh (GPSVS), an organisation set up by followers of Vinoba Bhave and Jayprakash Narayan in the late 1970s, inspired by ideas of decentralised democracy and community-based self-reliance. (The Vikas Sangh also partnered with the state government’s immunisation drives and sterilisation camps, often critiqued for the ‘target’ approach, in the late 1990s).

In the predominantly Muslim village of Hasanpur, immunisation for polio and family planning advocacy and use were stumbling along in the year 2000 when GPSVS began to organise women into self-help groups and mahila mandals in this and other villages. Salah became a member of a small-savings group, and encouraged Shama to sign up too.

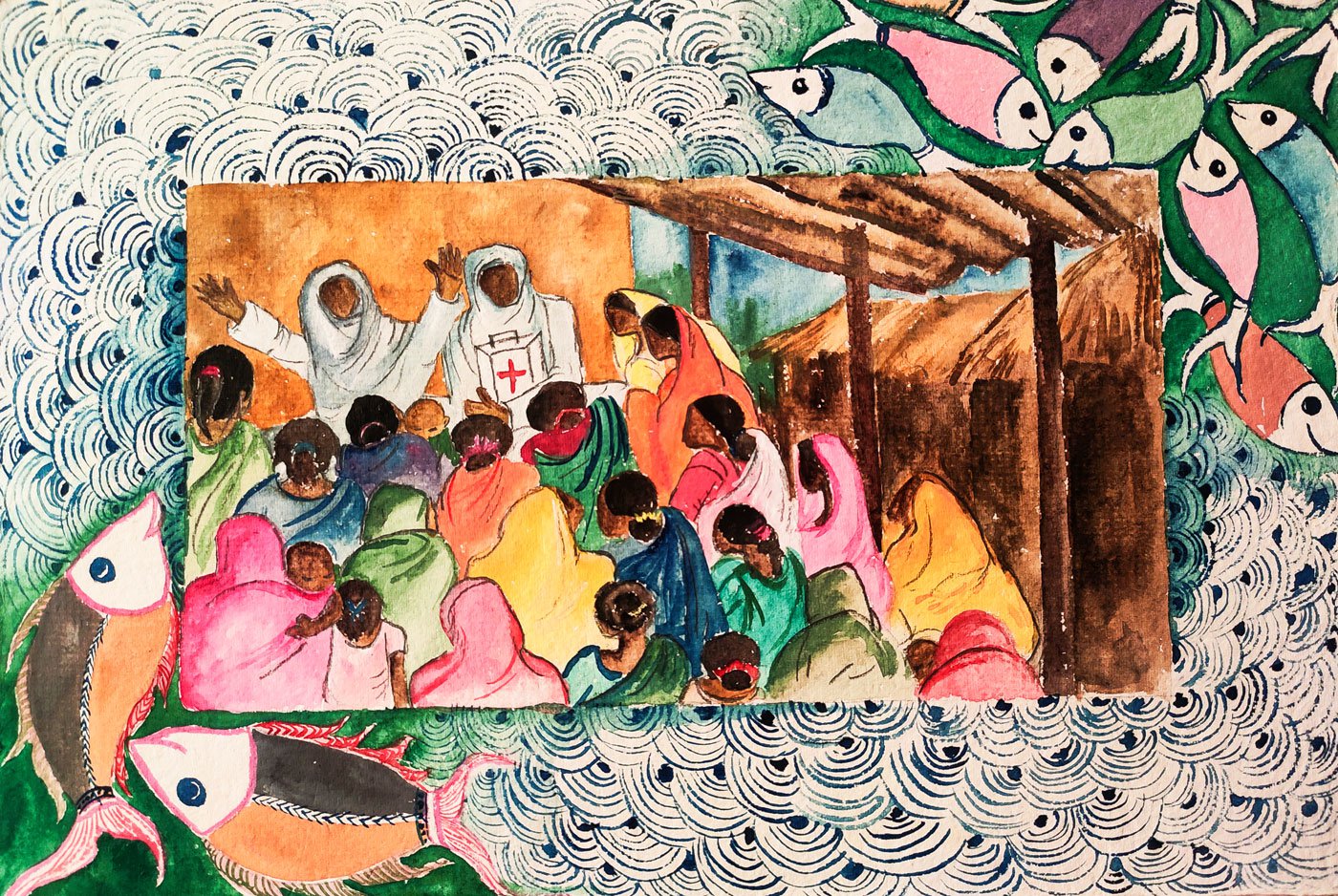

Over the last three years, the two women attended training programmes on menstruation, sanitation, nutrition and family planning organised by GPSVS. In nearly 40 villages of Madhubani district where the Vikas Sangh works, the organisation also began to equip women a ‘Saheli Network’ with a kit-bag containing menstrual hygiene products, condoms and contraceptive pills that the women could sell. This brought contraception to women’s doorstep, and that too through non-judgmental peers. In 2019, as the injectable DMPA became available under the brand-name Pari, that was added to the kit-bag.

Salah with ANM Munni Kumari: She and Shama learnt how to administer injections along with a group of about 10 women trained by ANMs (auxiliary-nurse-midwives) from the nearby PHCs

“About 32 women of the Saheli Network now form a sales network. We connected them to a local wholesaler, from whom they purchase in bulk at wholesale rates,” says Ramesh Kumar Singh, chief executive officer of GPSVS, who is based in Madhubani. For this, the organisation assisted some of the women with initial capital. “They are able to make a profit of Rs. 2 on every item sold,” adds Singh.

In Hasanpur, when a small number of women began to opt for the injectable regularly, they had to ensure that the next dose was taken no later than two weeks after the three-month gap between doses. That is when Shama and Salah learnt how to administer injections, along with a group of about 10 women who were trained by ANMs (auxiliary-nurse-midwives) from the nearby PHCs. (Hasanpur does not have a primary healthcare centre; the nearest PHCs are at Phulparas and Jhanjharpur, between 16 and 20 kilometres away).

Among those who have taken an Antara injection at the Phulparas PHC is Uzma (name changed), a young mother of three who had her children early and in quick succession. “My husband goes to Delhi and elsewhere for work. We decided that it’s okay to take the sui [injection] whenever he returns home,” she says. “Times are so tough now, we can’t afford a larger family.” Uzma adds that she is now considering a “permanent” solution through a tubal ligation.

The women who were trained to be ‘mobile health workers’ also help connect women who want to take the free-of-cost Antara injection to the PHCs where they have to register themselves. Village-level anganwadis are expected to also eventually make Antara available to women, say Salma and Salah. And a manual of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare for injectable contraception says it will be available in a third phase at sub-centres too.

Now, Shama says, most women in the village ensure “a break” after two children.

But this change took time coming to Hasanpur. “ Lamba laga [it’s been a while],” says Shama, “but we did it.”

Shama’s husband, Rehmatullah Abu, who is in his late 40s, has a medical practice in Hasanpur, though he does not have an MBBS degree. Supported by him, more than 15 years ago, she completed the madarsa board’s Alim-level examination, an intermediate pre-degree certification. That support, and her work with the women’s group, emboldened Shama to accompany her husband on his rounds, sometimes going along for deliveries, or keeping patients comfortable in the clinic in their house.

Shama and Salah though don’t believe that on matters of contraception they had to negotiate the sensitive space of religious beliefs in their predominantly Muslim village. Instead, they say, society itself has begun to view things differently over time

Shama was a child bride, barely a teen when she got married in 1991 and came to Hasanpur from Dubiahi in present-day Supaul district. “I used to observe strict purdah earlier; I hadn’t even seen the mohalla,” she says. Her work with the women’s group changed all that for her. “Now I can do a full check-up of a child. I can also administer injections or connect a saline drip. Itna kar lete hain [I can manage that much],” she says.

Shama and Rehmatullah Abu have three children. The eldest son is still unmarried at 28, she says proudly. Her daughter completed her graduation and is hoping to enroll for a BEd course. “Mashallah, she will be a teacher,” Shama says. The youngest son is in college.

Hasanpur’s women trust Shama when she tells them to keep their families small. “They come to me sometimes with some other health complaint, and I advise them on birth control. The smaller a family, the happier they will be.”

Shama holds daily classes in in the airy verandah of her house, paint peeling from the walls but its pillars and arches providing a sunlit teaching area for around 40 students, ages ranging from 5 to 16. She teaches them a blend of the school syllabus with practical lessons in embroidery or sewing, and music. And here, the teenage girls have access to Shama’s willing ear for queries.

Among her former students is Gazala Khatun, 18 years old. “The mother’s womb is the child’s first madarsa . All learning and good health starts there,” she says repeating a line she has learnt from Shama. “From what should be done during the monthly cycle to what is the correct age to get married, I have learnt all this. All the women in my family now use sanitary pads, not cloth,” she adds. “I’m also careful about nutrition. If I am healthy, I will have healthy children in the future.”

Salah (who prefers to not talk about her family) too has the trust of the community. She is now the leader of nine small savings groups of the Hasanpur Mahila Mandal, each with 12-18 women putting aside savings of Rs. 500-Rs 750 per month. The groups meet once a month. Often, there are several young mothers, and Salah encourages discussions on birth control.

S everal young mothers often attend local mahila mandal meetings where Salah encourages discussions on birth control

Jeetendra Kumar, Madhubani-based former chairman of GPSVS, who was also among its founding members in the late 1970s, says, “Our 300 women’s groups are named Kasturba Mahila Mandals and our attempt has been to make empowerment a reality for village women, even in conservative societies like this one [Hasanpur].” He stresses that the all-round nature of their work helps communities start trusting volunteers such as Shama and Salah. “There also used to be rumours in localities here that the Pulse Polio drops would make boys sterile. Change takes time…”

Shama and Salah though don’t believe that on matters of contraception they had to negotiate the sensitive space of religious beliefs in their predominantly Muslim village. Instead, they say, society itself has begun to view things differently, over time.

“I’ll give you an example,” says Shama. “Last year, my relative who has a BA degree, got pregnant again. She has three kids already. And she’d had an operation for the last one. I had warned her that she should be careful, her abdomen had been opened. She ended up having serious complications and had to undergo another surgery, this time to remove the uterus. They spent Rs. 3-4 lakh on the entire thing.” Incidents like this make other women keen to find and adopt safe contraceptive techniques, she adds.

Salah says people are now willing to consider with nuance what constitutes a gunaah or sin. “My religion also says that you must look after your child, ensure his good health, give him good clothes, raise him well…” she says. “ Ek darjan ya aadha darjan hum paida kar liye [if we’ve birthed a dozen or half a dozen children] and then they’re just allowed to roam free – our religion does not order us to give birth and leave the children to fend for themselves.”

The old fears have dissipated, adds Salah. “The mother-in-law no longer lords over a household. The son earns and sends money back home to his wife. She is the mukhiya [chief] of the house. We teach her about keeping a gap between children, about using an intra-uterine device, or pills or the injection. And if she has had two or three children, we advise her to get a surgery [sterilisation] done.”

The people of Hasanpur have responded well to these efforts. According to Salah: “Line pe aa gaye [people have fallen in line].”

PARI and CounterMedia Trust's nationwide reporting project on adolescent girls and young women in rural India is part of a Population Foundation of India-supported initiative to explore the situation of these vital yet marginalised groups, through the voices and lived experience of ordinary people.

Want to republish this article? Please write to [email protected] with a cc to [email protected]