'Freedom from fear' and 'Punishment-free zone' read the slogans on the school walls. These signify the end of corporal punishment. They take on a different meaning, though, when schools are occupied by the police, as they are around Dhinkia and Govindpur, the villages resisting the state's takeover of their farmland for Posco's mega power and steel project.

Children here grabbed national attention when they joined their parents in the protests against the forcible land acquisition. And still more when the fall in school attendance drew the wrath of Odisha's Women and Child Development Minister Anjali Behera. Her concern that children remain in school is unexceptionable. Her belief that they were not there only because they had joined the protests is misplaced.

In this state, millions remaining in the classrooms are unlikely to get an education. Besides, Odisha has “not served midday meals in most schools since mid-June,” says Biraj Patnaik, adviser to the Supreme Court's Food Commissioners. “And they are sitting on over Rs. 146 crores of last year's disbursement for the scheme from the central government.

But back to the villages. “Four of our six rooms are occupied by the police who are here to deal with the agitation,” says a teacher at the Balia nodal Upper Primary School. This school runs till Class 7. “Every morning, all the children assemble, we take attendance – and then dismiss Classes 1-5. How to teach them?” The police occupy space in several schools. They have vacated one in Balituth but remain in at least four others including Balia.

Ten-year-old Rakesh Bardhan and the other students are angry. One of them says: 'They are turning their guns on our parents and they want us to remain in school?'

“In school,” says angry 10-year-old Rakesh Bardhan in Govindpur, “they teach us the story of Baji Rout.” A 13-year-old boatman and legendary Odiya hero shot dead by the British when he refused to ferry them across a river in pursuit of freedom fighters. “They tell us, ‘you should emulate Baji Rout and the way he stood up for his homeland'. But when we stand up for ours, they react badly.”

How do their teachers feel about this? Bishwambar Mohanty, aged 14, scoffs: “What can they say? They know that if we lose our land and village there will be no school either.” One teacher says: “They have seen police fire rubber bullets on their parents. They've seen their betel vineyards and their homes destroyed. And said that all this is good for Odisha's development. How else can they react?” Another student asks: “They are turning their guns on our parents and they want us to remain in school?”

A team of the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights came here, concerned by the “misuse” of the children in the protests. At the end of their visit, while asking the protesters to keep children out, the team also called on the government “to withdraw police forces sheltered in schools meant for the education of children.”

“If the government orders us, obviously we will find other shelters,” Jagatsinghpur district superintendent of police S. Devdutt Singh told me.

Meanwhile, teachers have been given the additional task of talking to the parents of 'absentees'. “The BDO demands a daily report on attendance and how many parents we have met,” a teacher grumbles. “As if we don't have enough paperwork already, ‘with 74 records to keep updated'.”

Govindpur Upper Primary School has 240 students and four teachers. Of these, only one is a regular teacher. The others are shiksha sahayaks ('assistant teachers') and gana sikhyaks ('mass educators'). Last month the state recruited 20,000 shiksha sahayaks to fill vacancies amongst regular teachers. Many sahayaks are poorly-trained and ill-equipped to teach.

In the panchayat of the Posco area, there are only 'acting headmasters'. In many schools across the state, the headmaster's post remains vacant for years. There are also 29,000 vacancies for primary school teachers in Odisha. “They'd have to pay more if they filled those up properly,” grins one teacher. In Tirlochanpur village, 400 students go to a school without a single regular teacher.

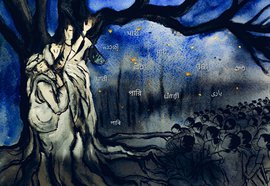

In Dhinkia and Govindpur, students participate in the protests against the state's takeover of their farmland for Posco's mega power and steel project

Shorn of the jargon offered under the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, this amounts to recruiting 'teachers' at pathetic salaries. Shiksha sahayaks get a consolidated Rs. 4,000. If they last six years, they might be absorbed as zilla parishad teachers. The gana sikhyak (also called 'volunteer teacher' under the Education Guarantee Scheme) is worse off. “They are least qualified and shouldn't be teaching, but they are,” says an official. They earn Rs. 2,250 to Rs. 2,500 a month. Less than what a landless labourer earns in 30 days of work under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme. Spending less by paying 'teachers' a pittance has helped gut the system. “Why will qualified people join this profession now?” asks one.

The poor quality breeds, as across the country, a huge private tuition industry. Some teachers earn more from tuitions. Others are not qualified to do even that. Some don't teach at all. And there's a welter of other problems. A spirited effort, within these limitations, to clear the mess and discipline the system by a committed education secretary has resulted in a backlash. Aparajita Sarangi now faces 85 cases filed against her in the courts by disgruntled school management committees and teachers.

Back in Dhinkia and Govindpur, students are less visible in the protests, but are still there. “Now,” says one, “a different small group goes each day.” These children seem to be up on Mark Twain's dictum: “Never let school interfere with your education.”

A version of this article was originally published in The Hindu on July 18, 2011.