“ Pankhe wale [windmills], blade wale [solar farms] are taking over our orans ,” says Sumer Singh Bhati, resident of Sanwata village. A farmer and herder, his home is adjacent to Degray oran in Jaisalmer district.

Orans are sacred groves, and considered common property resource, accessible to all people. Each oran has a deity who is worshipped by the villagers nearby, and the land around is kept inviolate by the community – trees cannot be cut, only fallen wood can be taken as firewood and nothing is allowed to be built here, and water bodies are holy.

But, says Sumer Singh, “they [renewable energy companies] have cut down centuries-old trees and uprooted grasses and shrubs. It seems nobody can stop them.”

Sumer Singh’s outrage is echoed by residents of hundreds of villages in Jaisalmer who find their orans being taken over by renewable energy (RE) companies. They say in the last 15 years, thousands of hectares of land in this district have been given over to windmills and fenced-in solar farms along with high tension power lines and micro grids to evacuate the power out of the district. All this has violently disturbed the native ecology and is destroying livelihoods of those who depend on these forests.

“There is nowhere left to graze. The grass is already gone [in March] and now our animals have only the leaves of ker and kejri trees to eat. They are not getting enough food and so they give less milk. It is down from 5 litres to 2 litres a day,” says pastoralist Jora Ram.

The semi-arid savanna orans are meant for the welfare of the community – they provide fodder, grazing, water, food and firewood to the thousands of people who live around them.

Left-Camels grazing in the Degray oran in Jaisalmer district. Right: Jora Ram (red turban) and his brother Masingha Ram bring their camels here to graze. Accompanying them are Dina Ram (white shirt) and Jagdish Ram, young boys also from the Raika community

Left: Sumer Singh Bhati near the Degray oran where he cultivates different dryland crops. Right: A pillar at the the Dungar Pir ji oran in Mokla panchayat is said to date back around 800 years, and is a marker of cultural and religious beliefs

Jora Ram says his camels have been looking thinner and weaker for some years now. “Our camels are used to eating up to 50 different grasses and leaves in a day,” he says. Even though high-tension lines run 30 metres above the ground, plants below are vibrating with the energy of the 750 MW coursing through, giving a shock. “Imagine a young camel who puts his entire mouth on a plant,” points out Jora Ram, shaking his head.

The 70 camels belong to him and his brother Masingha Ram from Rasla panchayat. In search of grazing grounds, the herd travel more than 20 kilometres a day in Jaisalmer district.

Masingha Ram says, “walls have gone up, [high tension] wires and pillars [wind energy] in our grazing areas has made it out of bounds for our camels. They fall into pits [dug for poles] and suffer grazes which turn infectious. These solar plates are no benefit to us.”

Members of the Raika pastoral community, the brothers are from a long line of camel herders, but now, “we are forced to do manual labour to feed ourselves,” as there is not enough milk to sell. Other jobs are not easily available, and they say, “at best one person in the family gets outside work.” The rest must stick to grazing.

Not just camel, but all herders are facing the same problem.

Shepherd Najammudin brings his goats and sheep to graze in the Ganga Ram ki Dhani oran , among the last few places he says where open grazing is possible

Left: High tension wires act as a wind barrier for birds. The ground beneath them is also pulsing with current. Right: Solar panels are rasing the ambient temperatures in the area

About 50 kilometres away or less as the crow flies, it’s around 10 a.m. and shepherd Najammudin has entered the Ganga Ram ki Dhani oran in Jaisalmer district. His 200 sheep and goat are scurrying and leaping looking for tufts of grasses to feed on.

Their 55-year-old herder from Naati village looks around and says, “this is the only patch of oran left around here. Open grazing is not so easily available anymore.” He estimates that he annually spends up to Rs. 2 lakh on buying fodder.

Rajasthan has 14 million cattle as of 2019, and the highest population of goats (20.8 million), 7 million sheep and 2 million camels. They have been badly hit by the closing off this common resource.

And it’s only going to get worse.

An estimated 10,750 circuit kilometres (ckm) of transmission lines will be laid in the second phase of the Intra-State Transmission System Green Energy Corridor Scheme. It was approved on January 6, 2022 by the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA) and will come up in seven states, including Rajasthan, says the 2021-2022 annual report of the union Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE).

It’s not just the loss of the grazing land. “When RE companies come in, they first cut all the trees in the area. So, all the native species of insects, birds and butterflies, moths, etc all die, and the ecological cycle gets disturbed; breeding areas of birds and insects is also destroyed,” Parth Jagani, a local environmental activist.

And the wind barrier created by the hundreds of kilometres of powerlines is killing birds in thousands, including Rajasthan’s state bird the GIB. Read: Great Indian Bustard: sacrificed for power

The arrival of solar plates is literally raising local temperatures. India is seeing extreme heat waves; in Rajasthan's desert climate, temperatures annually climb to over 50 degrees celsius. Data from an interactive portal on global warming of the New York Times shows that 50 years from now Jaisalmer will have a extra month of 'very hot days' – from 253 going upto 283.

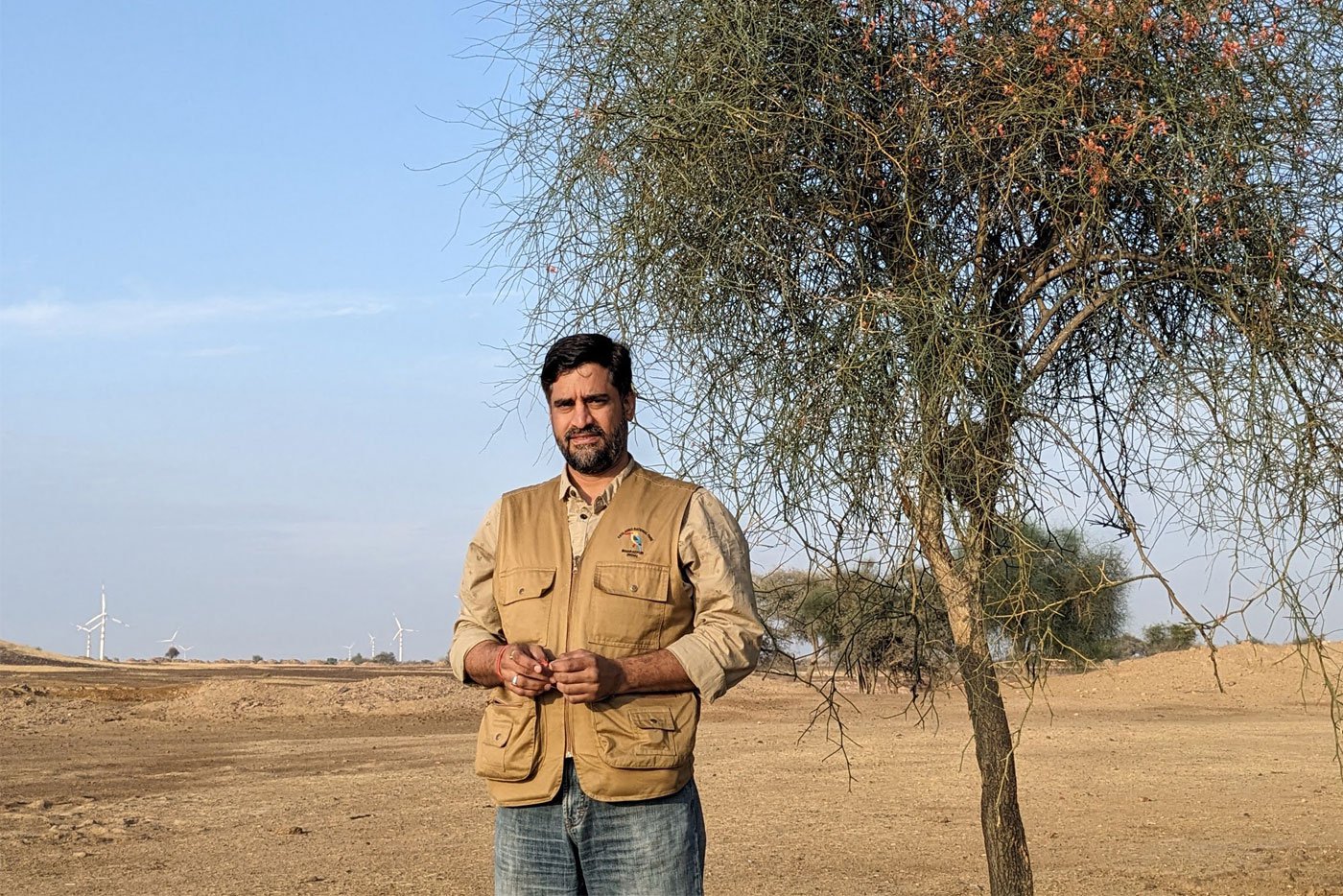

Dr. Sumit Dookia says the heat from solar panels is compounded by the loss of trees chopped to make way for RE. A conservation biologist, he has been studying the change in orans for decades. “Local environmental temperatures are shooting up because of the glass plates’ reflection.” He says that while 1-2 degree rise in temperature is expected due to climate change over the next 50 years, “now it is accelerated and native species of insects, especially pollinators will be forced to leave the area as temperatures rise.”

Left: Windmills and solar farms stretch for miles here in Jaisalmer district. Right: Conservation biologist, Dr. Sumit Dookia says the heat from solar panels is compounded by the loss of trees chopped to make way for renewable energy

A water body in the Badariya oran supports animals and birds

In December 2021, six more solar parks were approved in Rajasthan. During the pandemic, Rajasthan gained the maximum RE capacity – 4,247 MW was added in just 9 months (March to December) of 2021, adds the MNRE report.

Locals say this was a covert operation: “when the whole world was shut down due to lockdown, work went on continuously,” says local activist, Parth. Pointing to windmills stretching to the horizon he says, “this 15-km-road, from Devikot to Degray mandir, before lockdown there were no structures on either side.”

Explaining how things happen Narayan Ram says, “they come with police lathis , they get rid of us, and then they force their way, cutting trees, levelling the land.” He is from the Rasla panchayat and is sitting with other elders across from the Degray Mata mandir, a temple for the goddess who oversees the oran.

“We view the oran the way we view our mandir. It is our faith. It is a place to graze animals, for wild animals and birds to live, water bodies also, so it is like our devi [goddess]; camels, goats, sheep, all use it,” he adds.

Despite multiple attempts by this reporter to get the views of the Jaisalmer District Collector, no meeting was granted; the National Institute of Solar Energy under the MNRE has no contact details; and email enquiries at the MNRE have not been answered till the time of this going to press.

A local official at the state electricity corporation who said he was not authorised to speak, said they had received no instructions on any power grids going underground nor was there any slowdown of projects.*****

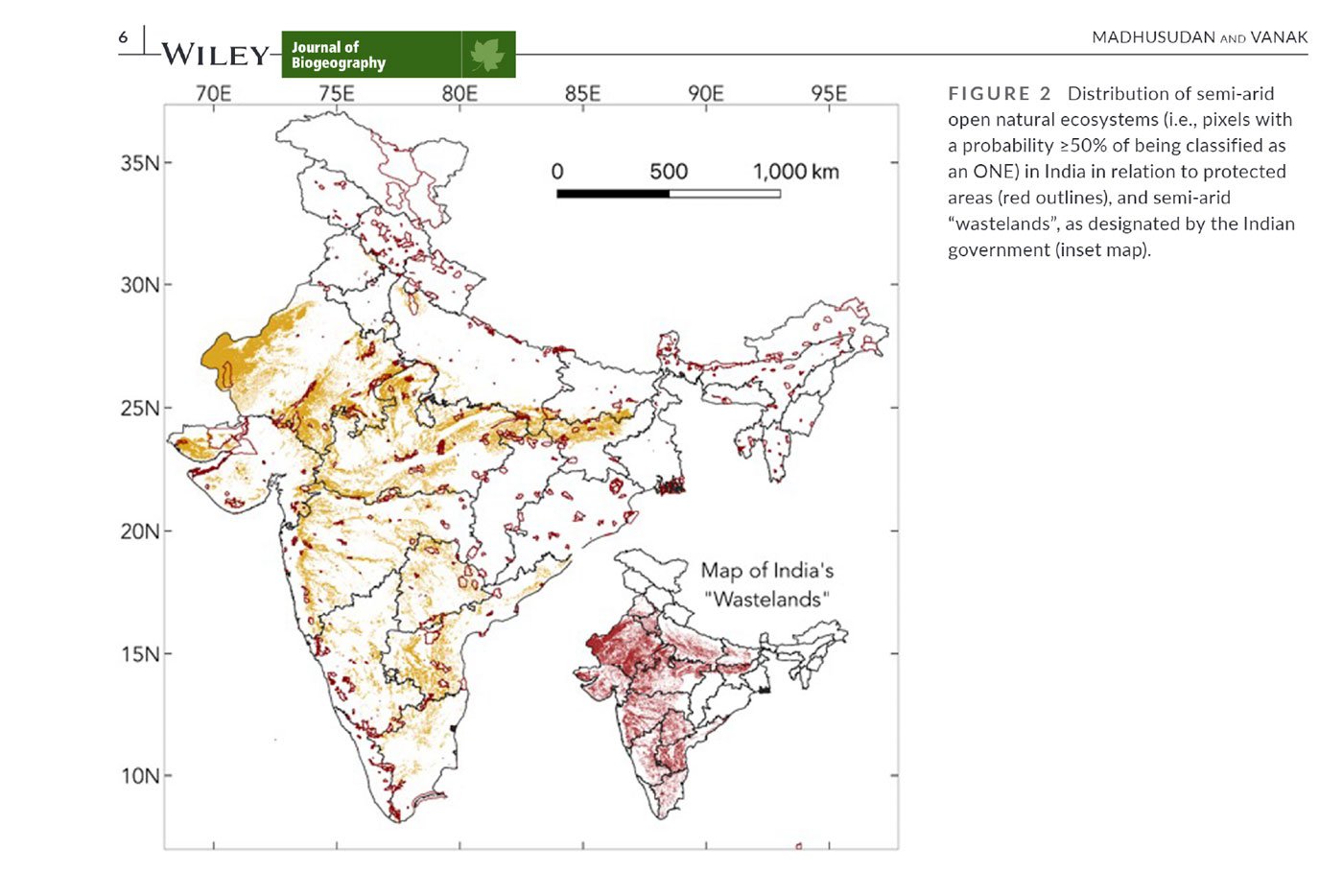

The ease with which RE companies have entered and grabbed land in Rajasthan has its roots in a colonial era nomenclature that clubs all non-revenue land as ‘wasteland’. This includes the semi-arid open savannas and grasslands seen here.

Despite senior scientists and conservationists publicly contesting this mis-categorisation, the Indian government has continued with publishing a Wasteland Atlas since 2005; the fifth edition was in 2019 but is not fully downloadable.

The Wasteland Atlas of 2015-16 classifies 17 per cent of India as grassland. Government policy officially declares grasslands, scrub and thorn forests, as ‘waste’ or ‘unproductive land’.

“India does not recognise dryland eco systems as having value in conservation, for livelihoods and for biodiversity and these lands become an easy target for conversion and irreparably damage the ecology,” says conservation scientist, Dr. Abi T. Vanak who has been fighting this mis-categorisation of grasslands for over two decades.

“A solar farm creates a wasteland where one didn’t exist before. You have taken a vibrant ecosystem and created a solar farm. It’s generating energy but is it green energy?” he asks. He says 33 per cent of Rajasthan is open natural ecosystems (ONEs) and not wasteland’ as categorised.

In a paper he co-authored with ecologist M.D. Madhusudan of the Nature Conservation Foundation, they wrote, “ONEs cover 10 per cent of India’s land but only 5 per cent of it is under Protected Areas (PA).” The paper is titled Mapping the extent and distribution of Indian’s semi-arid open natural ecosystems .

A map (left) showing the overlap of open natural ecosystems (ONEs) and ‘wasteland’; much of Rajasthan is ONE

It is these important grazing lands, that herder Jora Ram refers to when he says, “the government is giving away our future. We need to save the camel to save our community.”

Making matters worse, in 1999 the former Department of Wasteland Development was ironically renamed the Department of Land Resources (DoLR).

Vanak is calling out the government on “a techno-centric understanding of landscape and ecologies – trying to engineer and homogenise everything.” A Professor at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), he says, “native ecologies are not being respected, and we are ignoring peoples’ lived relationship with the land.”

Kamal Kunwar of Sanwata village says, “even bringing ker sangri from the oran is no longer possible.” The 30-year-old is especially upset about the loss of the small berries and beans of the native ker tree that are extensively used in local cooking, for which she is much admired.

The DoLR’s stated mission also includes ‘enhancing livelihood opportunities in rural areas.’ But by giving over land to RE companies, sealing off large tracts of grazing grounds, and making non-forest timber produce (NTFP) inaccessible, the opposite has in fact happened.

Kundan Singh is a herder in Mokla village in Jaisalmer district. The 25-year-old says that there are roughly 30 families of agro-pastoralists in his village and grazing has become a challenge. “They [RE companies] make a boundary wall and then we cannot enter to graze.”

Left- Young Raika boys Jagdish Ram (left) and Dina Ram who come to help with grazing . Right: Jora Ram with his camels in Degray oran

Kamal Kunwar (left) and Sumer Singh Bhati (right) who live in Sanwata village rue the loss of access to trees and more

Jaisalmer district is 87 per cent rural, and over 60 per cent of the people here work in agriculture and keep livestock. “There are livestock in every home in this region,” says Sumer Singh. “I can’t feed my animals enough.”

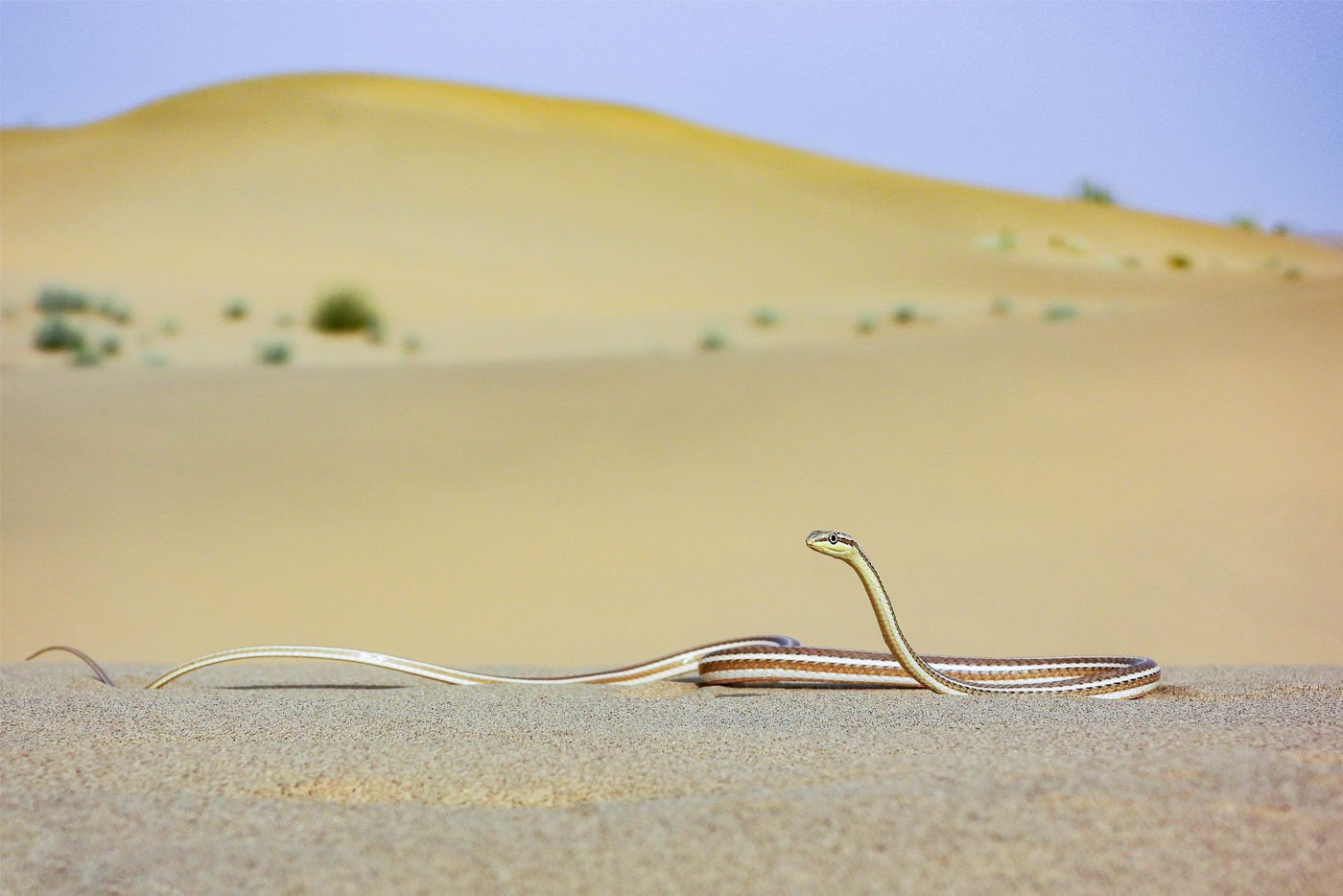

The animals feed on grass, of which Rajasthan has 375 species, says this paper titled, Pattern of Plant Species Diversity , published in June 2014. They are highly adapted to the scanty rainfall here.

But when RE companies take over the land, “the soil gets disturbed. Each tuft of a native plant is several decades old, and the ecosystem is up to hundreds of years old. You can’t replace them! Removing them leads to desertification,” points out Vanak.

Rajasthan has 34 million hectares of land says the India State of Forest Report 2021 , but only categorises 8 per cent as forest as when satellites are used to collect data on forests, they only recognise tree cover as ‘forest’.

But the forests of this state are home to numerous grassland species, many of which are threatened or endangered: the Lesser Florican breed and Great Indian Bustard, Indian grey wolf, Golden jackal, Indian fox, Indian gazelle, Blackbuck, Striped hyaena, Caracal, Desert cat and Indian hedgehog and more. Also in need of immediate conservation are the Desert Monitor lizard and Spiny-tailed Lizard.

The United Nations has named the decade 2021-2030 as the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration : “Ecosystem restoration means assisting in the recovery of ecosystems that have been degraded or destroyed, as well as conserving the ecosystems that are still intact.” Further, IUCN’s Nature 2023 programme lists ‘restoration of ecosystem’ as it’s No. 1 priority.

Jaisalmer lies in the critical Central Asian Flyway – the annual route taken by birds migrating from the Arctic to Indian Ocean, via central Europe and Asia

Orans are natural eco systems that support unique plant and animal species. Categorising them as ‘wasteland’ has opened them to takeovers by renewable energy companies

The Indian government is importing cheetahs to ‘save the grasslands’ and ‘open forest ecosystems’, or so says the Rs. 224 crore cheetah reintroduction plan announced in January 2022. But the cheetahs have barely been able to save themselves – five of the 20 that were imported have died, plus three cubs that were born here.

*****

A cheer went up in the orans when the Supreme Court ruled in 2018 that “...arid areas which support scanty vegetation, grass lands or ecosystems…need to be treated as forest land.”

But on the ground, nothing changed and RE contracts continue to be drawn up. Local activist, Aman Singh who has been working on getting legitimacy for these forests, filed an application in the Supreme Court for “Direction and Intervention”. The SC issued a notice on February 13, 2023 to the Rajasthan government to act.

“The government does not have sufficient database for orans . Revenue records are not updated, and many orans are not recorded and /or under encroachment,” says Singh, founder of Krishi Avam Paristhitiki Vikas Sansthan (KRAPAVIS), an organisation committed to revitalising commons, especially orans .

He says the status of ‘deemed forests’ should provide the orans with greater legal protection against mining, solar and wind farms, urbanisation, and other threats facing them. “If they [continue] to be under wasteland revenue category, they are vulnerable for allotment for other purposes,” he adds.

It will only get more difficult to hold on to orans as the Rajasthan Solar Energy Policy, 2019 document allows solar power plant developers to acquire agriculture land for developing in excess of ceiling limit, and there are no restriction on land conversion.

When pristine orans (right) are taken over for renewable energy, a large amount of non-biodegradable waste is generated, polluting the environment

Parth Jagani (left) and Radheshyam Bishnoi are local environmental activists . Right: Bishnoi near the remains of a GIB that died after colliding with powerlines

“India’s environmental laws are not auditing green energy,” says wildlife biologist, Dr. Sumit Dookia, Assistant Professor at Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University, New Delhi. “But the government can’t do anything as laws are supporting RE.”

Dookia and Parth are worried about the enormous amounts of non-biodegradable waste that is generated by the RE set-ups. “The leases for RE are given for 30 years, but the windmills and solar panels have a life of 25 years. Who will dispose and where,” asks Dookia.*****

“Sir sante rok rahe tho bhi sasta jaan [If even one tree is saved in exchange for a human head, it is still a bargain].” Radheyshyam Bishnoi is reciting a local proverb that “describes our relationship with our trees.” A resident of Dholiya, he lives near the Badriya oran and is one of the foremost voices on saving the Great Indian Bustard or godawan as it is locally known.

“Over 300 years ago, the raja of Jodhpur decided to build a fort and ordered his minister to bring wood from nearby Khetolai village. The mantri [minister] sent the army and when they reached, the Bishnoi people did not allow them to cut the trees. The mantri declared, ‘cut the trees and the people attached to them’.”

Local lore says that under Amrita Devi, each villager adopted a tree, but the army went at them and 363 people were killed before they had to stop.

“That feeling of giving our lives for the environment, is alive in us even today. It is alive,” he says.

Left: Inside the Dungar Pir ji temple in Mokla oran . Right: The Great Indian Bustard’s population is dangerously low. It’s only home is in Jaisalmer district, and already three have died after colliding with wires here

Sumer Singh says that of the 60,000 bigha oran in Degray, 24,000 bighas is owned by a temple trust. The remaining 36,000 although decreed locally as part of the oran , was not transferred to the trust by the government and, “in 2004 the government allotted it to wind energy companies. But we have fought and held on,” says Sumir Singh.

Elsewhere in Jaisalmer, he says, smaller orans don’t stand a chance as they are categorised as ‘wastelands’ and are being swallowed up by RE companies.

“This land looks rocky,” he says looking around his fields in Sanwata. “But we grow bajra , the most nutritious variety.” The Dongar Pirji oran near Mokla village is scattered with trees of kejri, ker, jaal and ber that are essential food and local delicacies for people and animals here.

“ Banjar bhumi [barren land]!” Sumer Singh is incredulous at the categorisation. “Give our local landless people who don’t have any other employment options, give them this land, they can grow ragi, bajra, and feed everyone.”

Mangi Lal runs a small shop on the highway between Jaisalmer and Khetolai, He says, “we are poor people. If money is offered to us for our land, how can we refuse?”

The reporter would like to thank Dr. Ravi Chellam, member of the Biodiversity Collaborative, for his help with this story.