Brown feathers speckled with white are scattered in the short grasses.

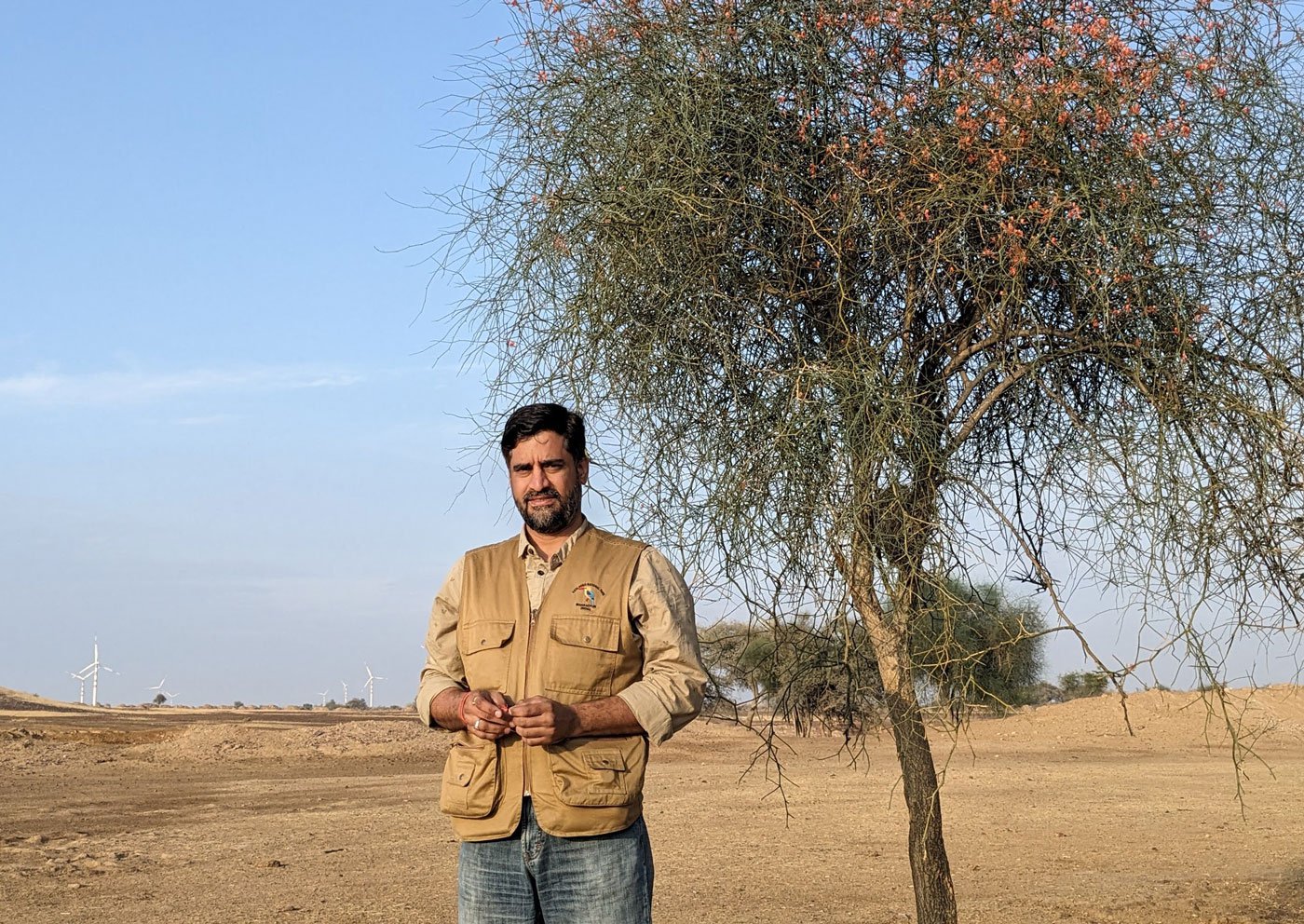

Searching keenly, Radheshyam Bishnoi circles the area in the fading light. He is hoping he is wrong. “These feathers don’t look plucked,” he says aloud. Then he makes a call, “Are you coming? I think I’m quite sure…,” he tells the person on the line.

Above us, like an omen in the sky, the 220-kilovolt high tension (HT) cables hum and crackle – now black lines silhouetted against the darkening evening sky.

Remembering his duty as a collector of data, the 27-year-old pulls out his camera and takes a series of close-up and mid-shots of the scene of the crime.

The next day, early in morning we are back on site – a kilometre from hamlet Ganga Ram ki Dhani, near Khetolai in Jaisalmer district.

This time there is no doubt. The feathers belong to the Great Indian Bustard (GIB), known locally as the godawan .

Left: WII researcher, M.U. Mohibuddin and local naturalist, Radheshyam Bishnoi at the site on March 23, 2023 documenting the death of a Great Indian Bustard (GIB) after it collided with high tension power lines. Right: Radheshyam (standing) and local Mangilal watch Dr. S. S. Rathode, WII veterinarian (wearing a cap) examine the feathers

Dr. Shravan Singh Rathore, a wildlife veterinarian is at the site on the morning of March 23, 2023. He says, on examining the evidence: “The death is due to collision with the HT wires, there is no doubt. It appears to have taken place three days prior to today, so on March 20 [2023].”

This is the fourth body of a GIB that Dr. Rathore, who works with Wildlife Institute of India (WII), has examined since 2020. The WII is the technical arm of the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEFCC) and state wildlife departments. “All the carcasses were found under HT wires. The direct link between the wires and these unfortunate deaths is clear,” he adds.

The dead bird is the critically endangered Great Indian Bustard ( Ardeotis nigricep s). And it’s the second one in just five months to crash and fall to its death after colliding with high tension wires. “This is the ninth death since 2017 [the year he began tracking],” says Radheshyam, a farmer from nearby village Dholiya in Sankra block of Jaisalmer district. An ardent naturalist, he keeps an eye out for the big bird. “Most of the godawan deaths have been right under HT wires,” he too adds.

The GIB is listed under Schedule I of the Wildlife (Protection) Act 1972 . Once seen in the grasslands of Pakistan and India, today there are totally only around 120-150 birds in the wild in the world , and their population is fragmented across five states. Around 8-10 birds have been sighted at the intersection of Karnataka, Maharashtra and Telangana, and four females in Gujarat.

The maximum number are right here in Jaisalmer district. “There are two populations – one near Pokaran and one in the Desert National Park – roughly 100 kilometres apart,” says Dr. Sumit Dookia, wildlife biologist who has been tracking these birds in their habitat – the grasslands of western Rajasthan.

Today there are totally only around 120-150 Great Indian Bustards in the world and most live in Jaisalmer district

'We have lost GIB in almost all areas. There has not been any significant habitat restoration and conservation initiative by the government,' says Dr. Sumit Dookia

Mincing no words he says, “We have lost GIB in almost all areas. There has not been any major significant habitat restoration and conservation initiative from the government.” Dookia is honorary scientific advisor at Ecology, Rural Development & Sustainability (ERDS) Foundation – an organisation that has been working in the area since 2015 to build community participation for saving the GIB.

“In my own lifetime I have seen these birds in flocks in the sky. Now I see the single bird, occasionally and rarely in flight,” points out Sumer Singh Bhati. In his forties, Sumer Singh is a local environmentalist and actively working to save the bustard and its habitat in the sacred groves of Jaisalmer district.

He lives in Sanwata village in Sam block, an hour away, but the death of the godawan has brought him and other concerned locals and scientists rushing to the site.

*****

About a 100 metres from the Degray Mata Mandir near Rasla village sits a life-size godawan made of plaster-of-paris. It can be seen from the highway – alone atop a platform inside a roped enclosure.

Locals have installed it as a mark of protest. “It was on the first death anniversary of the GIB that died here,” they tell us. The plaque written in Hindi translates to: ‘Near Degray Mata mandir on 16 September 2020, a female godawan collided with high tension lines. In its memory this monument has been built.’

Left: Radheshyam pointing at the high tension wires near Dholiya that caused the death of a GIB in 2019. Right: Sumer Singh Bhati in his village Sanwata in Jaisalmer district

Left: Posters of the godawan (bustard) are pasted alongwith those of gods in a Bishnoi home. Right: The statue of a godawan installed by people of Degray

For Sumer Singh, Radheshyam and other locals of Jaisalmer, the dying godawans and their loss of habitat is grimly symbolic of the lack of agency that their pastoral communities have over their surroundings, and the subsequent loss of pastoral lives and livelihoods.

“We are losing so much in the name of ‘development’,” says Sumer Singh. “And who is this development for?” He has a point – there is a solar farm 100 metres away, power lines run overhead, but electricity supply in his village is fitful, inconstant, and unreliable.

India’s RE capacity jumped 286 per cent in the last 7.5 years, proclaims the central Ministry of New and Renewable Energy. And in the last decade but more so in the last 3-4 years, thousands of renewable energy plants – both solar and wind – have been commissioned in this state. Among others, Adani Renewable Energy Park Rajasthan Ltd (AREPRL) is developing a 500 MW capacity solar park in Bhadla, Jodhpur and 1,500 MW capacity solar park in Fatehgarh, Jaisalmer. An inquiry via the website sent to the company asking if they are moving any lines underground, has not been answered at the time of this story being published.

The energy produced by solar and wind farms in the state is sent on to the national grid with the help of a huge network of power lines that act as a barrier in the flight path of bustards, eagles, vultures and other avian species. The RE projects will lead to a green corridor that passes through the GIB habitats of Pokhran and Ramgarh-Jaisalmer.

Solar and wind energy projects are taking up grasslands and commons here in Jaisalmer district of Rajasthan. For the local people, there is anger and despair at the lack of agency over their surroundings and the subsequent loss of pastoral lives and livelihoods

Jaisalmer lies in the critical Central Asian Flyway (CAF) – the annual route taken by birds migrating from the Arctic to Indian Ocean, via central Europe and Asia. An estimated 279 populations of 182 migratory waterbird species come through this route, says the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. Some of the other birds are the endangered Oriental White-backed vulture ( Gyps bengalensis ), Long-billed ( Gyps indicus ) , Stoliczka's Bushchat ( Saxicola macrorhyncha ) , Green Munia ( Amandava formosa ) and MacQueen's or Houbara Bustard ( Chlamydotis maqueeni ) .

Radheshyam is also an avid photographer and his long focus tele lens has thrown up disturbing images. “I have seen pelicans landing on a field of solar panels at night because they think it’s a lake. The hapless bird then slips on the glass and its delicate legs are irreversibly injured.”

Powerlines are killing not just bustards, but a staggering estimated 84,000 birds a year within a 4,200 square kilometre area in and around the Desert National Park in Jaisalmer, says a 2018 study by the Wildlife Institute of India. “Such high mortality rate [of the bustard] is unsustainable for the species and a sure cause of extinction.”

The danger is not just in the sky but on the ground – large areas of grassland commons, sacred groves or orans as they are referred to here, are now dotted with whirling 200-metre-tall windmills placed at 500 metre intervals, and hectare upon hectares of walled enclosures for solar farms. The intrusion of renewable energy into sacred groves where all communities insist even a branch cannot be cut, has turned grazing into a game of snakes and ladders – pastoralists can no longer tread a direct path, but instead must go round fences and dodge windmills and their attendant microgrids.

Left: The remains of a dead griffon vulture in Bhadariya near a microgrid and windmill. Right: Radheshyam tracks

godawans

to help keep them safe

“If I leave in the morning, I get home only by evening,” says Dhanee (she uses only this name). The 25-year-old must go into the forest to bring grass for her four cows and five goats. “I get a shock from the wires sometimes when I take my animals into the forest.” Dhanee’s husband is studying in Barmer town, and she manages their six bigha (roughly 1 acre) of land and their three boys aged 8, 5 and 4 years.

“We have tried to raise questions with our MLA and the District Commissioner (DC), but nothing has happened,” says Murid Khan, Gram Pradhan of Degray in Rasla village of Sam block in Jaisalmer.

“Six to seven lines of high-tension cables have been installed in our panchayat,” he points out. “It is in our orans [sacred groves]. When we ask them, ‘ bhai who has given you permission’, they say ‘we don’t need your permission’.”

On March 27, 2023, days after the incident, in a question asked in the Lok Sabha, the Minister of State for Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Shri Ashwini Kumar Choubey said that important GIB habitats would be designated into national parks (NPs).

Of the two habitats, one is already designated a NP and the other is defence land, but bustards are not safe.

*****

On April 19, 2021, in response to a writ petition, the Supreme Court ruled that, “in the priority and potential bustard area, where it is found feasible to convert the overhead cables into underground powerlines the same shall be undertaken and completed within a period of one year, and till such time diverters [plastic discs that reflect light and warn off birds] shall be hung from the existing powerlines.”

The SC judgement lists 104 km of lines to go underground, and 1,238 km of lines to have diverters in Rajasthan.

'Why is the government allowing such big-sized renewable energy parks in GIB habitat when transmission lines are killing birds,' asks wildlife biologist, Sumit Dookia

Two years later – April 2023 - the SC’s ruling to send lines underground has been completely ignored and plastic diverters affixed on only a few kms – in areas where it gets public and media attention near major roads. “As per available research, bird diverters reduce collision to a great extent. So theoretically, this death could have been averted,” says wildlife biologist, Dookia.

The native bustard is at risk in what is their only home on this planet. Meanwhile we have rushed to make a home for a foreign species – a majestic five-year plan to spend Rs. 224 crore on bringing African cheetahs to India. The outlay covers flying them in special aircrafts, building secure enclosures, hi-quality cameras, and observation watchtowers. Then there is the tiger whose population is increasing and its budgetary allocation stands at a generous Rs.300 cr in 2022.

*****

An imposing member of the avian species, the Great Indian Bustard stands a metre tall and weighs around 5-10 kilograms. It lays only one egg a year, and in the open. The increasing population of feral dogs in the area has put bustard eggs at risk. “The situation is grim. We need to find ways to sustain this population and leave some [inviolate] area for this species,” says Neelkanth Bodha, Programme Officer with the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) that runs a project in the area.

A terrestrial species, it prefers to walk. When it does fly, it’s a majestic sight – its wingspan of around 4.5 feet holding up the heavy body as it glides through the desert skies.

'The

godawan

doesn’t harm anyone. In fact, it eats small snakes, scorpions, small lizards and is beneficial for farmers,”'

says Radheshyam

Not only is the Great Indian Bustard at risk, but so are the scores of other birds that come through Jaisalmer which lies on the critical Central Asian Flyway (CAF) – the annual route taken by birds migrating from the Arctic to Indian Ocean

The mighty bustard has eyes on the side of its head, and it cannot see dead ahead. So, it either hits the high-tension wire in a head-on collision or tries to swerve at the last minute. But like a trailer truck that can’t take sharp turns, the GIB’s sudden change of direction is often too late, and some part of its wing or head slams into the wires situated at heights of 30 metres and above. “If the electric shock on encountering the wires don’t kill it, the fall usually does,” says Radheshayam.

In 2022, when locusts entered India through Rajasthan, “it was the presence of the godawan that saved some fields as they ate up locusts in thousands,” recalls Radheshyam. “ Godawan doesn’t harm anyone. In fact, it eats small snakes, scorpions, small lizards and is beneficial for farmers,” he adds.

He and his family own 80 bighas (roughly 8 acres) of land on which they grow guar and bajra , and sometimes a third crop if there is winter rain. “Imagine if there were not 150 GIB, but in thousands, such a serious calamity like locusts’ invasion would be reduced,” he adds.

To save the GIB and ensure its habitat is undisturbed requires attention to a relatively small area. “We can make that effort. It’s not such a big deal to do. And there is a court order to send lines underground and not give permission for any more lines,” says Rathore. “Now the government should really stop and think before it’s all over.”

The reporter would like to thank Dr. Ravi Chellam, member of the Biodiversity Collaborative for his generous help with this story.