Chandrika Behera is nine years old and has been out of school for almost two years. She is among 19 students of Barabanki village who should be in Class 1 to 5, but these children have not attended school regularly since 2020. Her mother just won’t send her, she says.

Barabanki got its own school in 2007, but it was closed down in 2020 by the Odisha government. Primary school children, mostly Santhal and Munda Adivasis from the village like Chandrika, were asked to enrol in the school in Jamupasi village about 3.5 kilometres away.

“Kids cannot walk that much daily. And they’re all getting into fights with one another on the long walk,” points out Mami Behera, Chandrika’s mother. “We are poor labourers. Are we to go find work or accompany children to and from school every day? The authorities should just re-open our own school,” she adds.

Until then, she shrugs helplessly, the 6 to 10-year-olds like her youngest child, just have to go without an education. In her 30s, the mother also fears that there may be child kidnappers in the forest here in Danagadi block of Jajpur district.

For her son, Jogi, Mami did manage to arrange a used bicycle. Jogi is studying in Class 9 at another school 6 km away. Her older daughter, Moni is in Class 7 and must walk to the school in Jamupasi. The youngest Chandrika, has to stay home.

“Our generation has walked and climbed and worked till our bodies gave way. Should we expect the same for our children too?” Mami asks.

Left: After the school in their village,

Barabanki

shut down, Mami (standing in a saree) kept her nine-year-old daughter, Chandrika Behera (left) at home as the new school is in another village, 3.5 km away. Right: Many children in primary school have dropped out

The 87 households in Barabanki are predominantly Adivasis. Some till small parcels of land, but most are daily wage labourers going as far as Sukinda, 5 km away, to work at a steel plant or cement factory. A few men have migrated to Tamil Nadu, to work at a spinning mill or in a beer can packaging unit.

In Barabanki, the school closure also threw up a doubt about the availability of school mid-day meals – an essential part of family meal planning for the very poor. Kishore Behera says, “For at least seven months, I did not get either the cash or the rice that was promised as an alternative to the hot cooked school meal.” Some families received money in their accounts in lieu of the meal; at times they were told there would be a distribution in the premises of the new school – 3.5 km away.

*****

Puranamantira is a neighbouring village in the same block. It’s the first week of April 2022. At noon, there is a flurry of activity on the narrow road leading out of the village. The back road is suddenly full of women and men, the odd grandmother and a couple of older teenage boys on bicycles. Nobody speaks as every last hint of energy conserved; gamchas (a towel-like scarf) and saree-ends are pulled low over foreheads against the midday sun, a searing 42 degrees Celsius.

Ignoring the heat, Puranamantira’s residents are out walking 1.5 km to collect their little boys and girls from school.

Deepak Malik is a resident of Puranamantira and a contract worker at a cement plant in Sukinda – Sukinda valley is known for its vast chromite reserves. Like him, others in the scheduled caste-dominated village are acutely aware that a decent education is the children’s ticket to better prospects. “Most of our village has to work if they want to eat that night,” he says. “That is why the construction of a school building in 2013-2014 was such a huge occasion for all of us.”

Since the pandemic in 2020, Puranamantira has not had a primary school for the 14 children who should be in Class 1-5, says Sujata Rani Samal, a resident in the village of 25 households. Instead, the young, primary schoolers have had to trudge the 1.5 km distance to Chakua, a neighbouring village located across a busy railway line.

Left: The school building in Puranamantira was shut down in 2020. Right: 'The construction of a school building in 2013-2014 was such a huge occasion for all of us,' says Deepak Malik (centre)

Parents and older siblings walking to pick up children from their new school in Chakua – a distance of 1.5 km from their homes in Puranamantira. They

cross a busy railway line while

returning home with the children (right)

To avoid the railway line one can use the motorable road with an overbridge, but the distance increases to 5 km. A shorter road snakes past the old school and a couple of temples at the edge of the village before ending at the railway embankment leading up to the Brahmani railway station.

A goods train screams past.

Every ten minutes, goods and passenger trains cross Brahmani, on the Howrah–Chennai main line of the Indian Railways. And so, no family in Puranamantira allows their child to walk to school unaccompanied by an adult.

The tracks are still vibrating as everyone scurries across before the next train comes along. Some children slide-jump-skip down the embankment; the smallest ones are hastily hoisted up and down the embankment. Stragglers are hurried along. It’s a 25-minute-hike for grubby feet, calloused feet, sunburnt feet, bare feet, too-tired-to-walk-any-longer-feet.

*****

The primary schools in Barabanki and Puranamantira are among nearly 9,000 schools closed in Odisha — the official term is ‘consolidated’ or ‘merged’ with a neighbouring village’s school — through a Union government programme called ‘Sustainable Action for Transforming Human Capital (SATH)’ in the education and health sectors.

SATH-E was launched in November 2017, to ‘reform’ school education in three states—Odisha, Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh. The aim was to make “the entire governmental school education system responsive, aspirational and transformational for every child”, according to a 2018 Press Information Bureau

release

.

The ‘transformation’ in Barabanki, where a village school was closed, is a little different. The village had one diploma holder, a few who completed their Class 12, and several who failed matriculation. “Now we may not have even that,” says Kishore Behera, chairperson of the now non-existent school’s management committee.

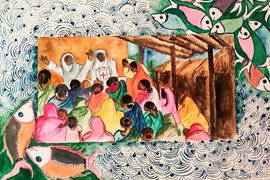

Left: Children in class at the Chakua Upper Primary school. Right: Some of the older children in Barabanki, like Jhilli Dehuri (in blue), cycle 3.5 km to their new school in Jamupasi

The ‘consolidation’ of primary schools with a selected school in a neighbouring village is a euphemism for closing down schools with a very small number of students. The then CEO of Niti Aayog, Amitabh Kant described the consolidation (or school closures) as one among "bold and pathbreaking reforms" in a November 2021 report on SATH-E.

That’s not how young Siddharth Malik of Puranamantira would describe the pain in his legs from walking long distances daily to his new school in Chakua. He has ended up missing school on many occasions, says his father, Deepak.

Of the nearly 1.1 million government schools in India, approximately 4 lakh have fewer than 50 students, and 1.1 lakh have fewer than 20 students. The SATH-E report referred to these as “sub-scale schools” and listed their deficiencies: teachers with no subject-specific expertise, a lack of dedicated principals, and no playgrounds, boundary walls and libraries.

But parents in Puranamantira point out that the additional amenities could have been built in their own school.

Nobody is certain if the school in Chakua has a library; it does have a boundary wall that was absent in their old school.

In Odisha, the third phase of the SATH-E project is currently underway. A total of 15,000 schools are identified for “consolidation” in this phase.

*****

It is 1 p.m. and Jhilli Dehuri, a Class 7 student and her schoolmate, are pushing their cycles home to Barabanki. She is often sick from the long and tiring journey, and so is not able to attend school regularly

Jhilli Dehuri is struggling to push her cycle uphill, as she nears home. In her village in Barabanki, an orange tarpaulin sheet is spread in the shade of a big mango tree. Parents have gathered here to discuss the schooling problem. Jhilli arrives exhausted.

Barabanki's upper primary and older students (from ages 11 to 16) attend school in Jamupasi, 3.5 km away. They find both walking and cycling in the noon sun exhausting, says Kishore Behera. His brother’s daughter, who started Class 5 in 2022 after the pandemic and was still unfamiliar with the long walk, fainted while walking home the previous week. Strangers from Jamupasi had to bring her home on a motorbike.

“Our kids don’t have mobile phones,” Kishore says, “nor is there any practice in schools of keeping parents’ phone numbers handy for emergencies.”

Across Sukinda and Danagadi blocks in Jajpur district, scores of parents in remote villages spoke about the dangers of travelling long distances to school: it’s a walk through a dense forest or along a busy highway, or across a railway line, down a steep hill, across trails flooded by monsoon streams, on village tracks where feral wild dogs prowl, through fields known to be visited by herds of elephants.

The SATH-E report says that Geographic Information System (GIS) data was used to identify the prospective new schools’ distance from those listed for closure. However, the neat mathematical calculations of GIS-based distances do not reflect these ground realities.

Left: Geeta Malik (in the foreground) and other mothers speak about the dangers their children must face while travelling to reach school in Chakua. From their village in Puranamantira, this alternate motorable road (right) increases the distance to Chakua to 4.5 km

Mothers have worries beyond the train and the distance, says Geeta Malik, a former panchayat ward member from Puranamantira. “The weather has been unpredictable in recent years. In the monsoon, it’s sometimes sunny in the morning and by the time school closes, there is a storm. How do you send a child to another village in these circumstances?”

Geeta has two boys, one aged 11 and in Class 6, and a six-year-old who has just started school. Her family have been

bhagachashis

(sharecroppers) and she would like her boys to fare better, hopefully earn well and buy their own plot of agricultural land.

Every one of the parents gathered under the mango tree conceded that when their village primary school closed, their children had either stopped attending school altogether or had become irregular. Some had skipped up to 15 days a month.

In Puranamantira, when the school closed, the anganwadi center for children younger than 6 years was also shifted out of the school complex and is now about 3 km away.

*****

The village school for many, is a symbol of progress; a totem of possibilities and fulfilled aspirations.

Madhav Malik, is a daily-wage labourer who studied till Class 6. He says the arrival of a school in Puranamantira village in 2014 seemed to announce better years for his sons, Manoj and Debashish, “We took great care of our school, because it was a symbol of our hope.”

The classrooms of the now-closed government primary school here are spotlessly clean. The walls are painted white and blue and filled with charts displaying the Odia alphabet, numerals and pictures. A blackboard is painted on one wall. With classes suspended, villagers decided that the school is the most sacred space available for community prayers; one classroom is now converted into a room to gather for kirtans (devotional songs). Brassware is arranged against a wall beside a framed picture of a deity.

Left: Students of Chakua Upper Primary School. Right: Madhav Malik returning home from school with his sons, Debashish and Manoj

Besides taking care of the school, Puranamantira’s residents are committed to ensuring that their children continue to get a proper education. They have organised tuition classes for every student in the village, conducted by a teacher who cycles in from another village 2 km away. Deepak says, often on rainy days, he or another resident fetches the tutor on a motorbike to ensure tuition classes are not skipped because the main road is flooded. The tuition sessions are held in their old school, each family paying the tutor Rs. 250 to Rs. 400 per month.

“Almost all the learning happens here, in the tuition class,” says Deepak.

Outside, in the sparse shade of a

palash

tree in full, fiery bloom, residents continue to discuss what the school closure signifies. Access to Puranamantira is challenging when the Brahmani floods in the monsoon. Residents have experienced medical emergencies when ambulances are unable to come, and days without electricity supply.

“The closing of the school seems to be a sign that we’re slipping back, that things will get worse,” says Madhav.

Global consulting firm Boston Consulting Group (BCG), the union government’s partner in the SATH-E project, has called it a “

marquee education transformation program

” that shows improved learning outcomes.

But in village after village in these two blocks of Jajpur and elsewhere in Odisha, parents say that access to education itself has become a challenge due to school closures.

Left: Surjaprakash Naik and Om Dehuri (both in white shirts) are from Gunduchipasi where the school was shut in 2020. They now walk to the neighbouring village of Kharadi to attend primary school. Right: Students of Gunduchipasi outside their old school building

Gunduchipasi village got a school as far back as 1954. Located in Sukinda block, this village in the Kharadi hill forest area is occupied entirely by members of the Sabar community, also known as Shabar or Savar and listed as a Scheduled Tribe in the state.

Thirty-two of their children were attending the local village government primary school before it was shut down. Once schools reopened, children were required to walk to the neighbouring village of Kharadi. It’s a mere kilometre away if one walks through the forest. Alternatively, there is the busy main road, a dangerous route for small children.

While attendance has dropped, parents admit it’s a trade-off between safety and the mid-day meal.

Om Dehuri, in Class 2, and Surjaprakash Naik, in Class 1, say they walk to school together. They carry water in plastic bottles but no snack or any money for it. Rani Barik, in Class 3, says she takes an hour but that’s mostly because she’s dawdling and waiting for friends to catch up.

Rani’s grandmother Bakoti Barik says she cannot understand how it made any sense to close their school of six decades and send children through a forest to a neighbouring village. “There are dogs and snakes, sometimes a bear – will a parent in your city believe this is a safe way to go to school?” she asks.

Class 7 and 8 kids are now in charge of getting the younger lot there and back. Subhashree Behera, in Class 7 has a tough time controlling her two younger cousins Bhumika and Om Dehuri. “They don’t always listen to us. If they run off, it’s not easy to follow each one,” she says.

Mamina Pradhan’s kids – Rajesh in Class 7, and Lija in Class 5 – walk to the new school. “The kids walk about an hour, but what choice do we have?” says this daily-wage labourer seated in her home made of bricks and straw with a thatched roof. She and her husband Mahanto work on other people’s land in the farming season and look for non-agricultural work in the off-season.

![‘Our children [from Gunduchipasi] are made to sit at the back of the classroom [in the new school],’ says Golakchandra Pradhan, a retired teacher](/media/images/10b-_PAL0682-KI.max-1400x1120.jpg)

Left: Mamina and Mahanto Pradhan in their home in Gunduchipasi. Their son Rajesh is in Class 7 and attends the school in Kharadi. Right: ‘Our children [from Gunduchipasi] are made to sit at the back of the classroom [in the new school],’ says Golakchandra Pradhan, a retired teacher

Eleven-year-old Sachin (right) fell into a lake once and almost drowned on the way to school

Parents say the quality of education in their Gunduchipasi school was much better. “Here our children got personal attention from the teachers. [In the new school], our children are made to sit at the back of the classrooms,” says Golakchandra Pradhan, 68, a village leader.

In nearby Santarapur village, also in Sukinda block, the primary school closed in 2019. Children now walk 1.5 km to the school in Jamupasi. Eleven-year-old Sachin Malik fell into a lake while trying to avoid a wild dog chasing him. “It happened in late 2021,” says Sachin’s older brother Sourav, 21, a worker in a steel plant in Duburi, 10 km away. He adds, “Two older boys saved him from drowning, but everyone was so frightened that day that the next day several kids from the village didn’t go to school.”

The feral dogs on the Santarapur-Jamupasi route have attacked adults too, says Labonya Malik, a widow who works as a helper to the mid-day meal cook at the Jamupasi school. “It’s a pack of 15-20 dogs. I once fell on my face when they chased me, eventually jumping over me. One bit my leg,” she says.

In the 93 households of Santarapur, the residents are mainly from scheduled caste and other backward class families. There were 28 children attending the village primary school when it closed. Only 8-10 attend school regularly now.

Ganga Malik of Santarapur, in Class 6 in Jamupasi, stopped going to school after falling into the seasonal lake at the edge of the forest path. Her father, Sushant Malik, a daily-wage labourer, recalls the incident: “She was washing her face at the lake when she slipped in. She was almost drowning by the time she was rescued. After that she began to skip school a lot.”

In fact, Ganga couldn’t muster the courage to attend school for her final exams, but says, “I was promoted anyway.”

The reporter would like to thank the staff of Aspire-India for their assistance.