Meena Yadav alternates between Bhojpuri, Bangla, and Hindi as she handles her customers, while also talking to friends, and strangers stopping by to ask her for directions in Lake Market, a multicultural hub in south Kolkata. “It [language] is not a problem in Kolkata,” she says, speaking of the difficulties she faces in her everyday life as a migrant.

“

Yeh sirf kehne ka baat hain ki Bihari log Bihar mein rahega

[It is easy to say Bihari people will stay in Bihar]. The fact is that all the hard physical labour is done by us. All the porters, water carriers, and coolies are Biharis. This is not the Bengalis’ cup of tea. You go visit New Market, Howrah, Sealdah…you will find the Biharis bearing heavy loads. But they don’t get any respect even after putting in so much hard work. Biharis call everyone 'babu'…but they [Biharis] are seen as lowly people. The flesh of the mango is for the Bengali babus, and the stone of the fruit remains for us,” she continues without a pause.

Meena Yadav moves deftly between language and the politics of identity.

“In Chennai we faced difficulties [in communication],” she continues. “They don’t respond to Hindi or Bhojpuri. They speak in their language which we don’t know. But not here,” Meena says. “See, there is no single Bihari language. At home we speak in 3-4 languages. Sometimes we speak Bhojpuri, sometimes Hindi, sometimes Darbhangiya [Maithili] and sometimes Bangla. But we feel at ease mostly with Darbhangiya,” says this 45-year-old corn seller from Chhapra in Bihar.

“We also use the Aarah and Chhapra

boli

. No problem at all, whatever language we want to talk in, we do,” she says, with the astonishing ease of a polyglot. And yet, she does not want to fool herself with the idea that her knowledge of all these languages has got anything to do with her exceptional skills.

Meena Yadav, a migrant from Bihar, selling corn in southern Kolkata's Lake Market area can alternate between Bhojpuri, Bangla, Maithili and Hindi with ease while doing business. She can also converse in Aarah and Chhapra boli

Talk of ‘celebrating ways of expressing the world in its multiplicity’ must be reserved for the director general of UNESCO (which hosts the International Mother Language Day). As for Meena, it is quite straightforward. She needs to learn the language of her masters, her employers, her customers, her immediate community. “Knowing so many languages may be good, but we learnt them because we had to survive,” she says.

On this International Mother Language Day, PARI reached out to people like Meena – poor migrants, often outsiders in their own nation, and separated from the language they were born into. We tried to enter the linguistic universe they inhabit, preserve and create as they live in different parts of the country.

Shankar Das, a migrant worker in Pune faces a peculiar challenge after returning home to Borkhola block in Cachar district of Assam. While growing up in his village Jarailtala, he was surrounded by Bangla speaking people. So, he never learnt Assamese, the official language of the state. He left home when he was in his twenties and in the decade and a half that he spent in Pune he honed his Hindi and learnt Marathi.

“I know Marathi very well. I have travelled the length and breadth of Pune, but I cannot speak Assamese. I can understand but can’t speak,” explains the 40-year-old. When Shankar lost his job as a labourer in a machinery workshop in Pune during the Covid-19 pandemic he was forced to return to Assam and look for work. Unable to get any in his village of Jarailtala, he went to Guwahati but had no luck because he did not know Assamese.

Meena Yadav is quite clear. There is no question of celebrating multiplicity of expression for her. 'Knowing so many languages may be good, but we learnt them because we had to survive,' she says

“It is difficult to even board a bus here forget about talking to an employer,” he says. “I am thinking of returning to Pune. I will get work and the language also will not be such a problem.” His hearth is no longer where his home is.

About two thousand kilometres away from Guwahati, in the national capital, 13-year-old Praful Surin, is struggling to learn Hindi to stay in school. When his father died in an accident, he was forced to join his bua (father’s sister) and come to Munirka village in New Delhi, 1,300 kilometres away from his home in Pahantoly hamlet in Gumla, Jharkhand. “I felt lonely when I came here,” he says. “No one knew Mundari. All of them spoke Hindi.”

He had learnt some letters of the Hindi and English alphabets in his village school before he shifted to this city, but not enough to understand or express himself. After two years of schooling in Delhi and some special tuition classes that bua organised, he can now speak a little Hindi while in school or while playing with friends. “But at home, I talk to bua in Mundari. That is my mother tongue," he says.

Another 1,100 kilometre away from Delhi, in Chhattisgarh, 10-year-old Priti does not want to continue with the school she is enrolled in. She is staying with her parents, but away from a language she feels at home in.

Priti's parents, Lata Bhoi, 40 and her husband Surendra Bhoi, 60 are Malua Kondh Adivasis. They have come to Raipur from Kendupara village in Kalahandi, Odisha to work as caretakers of a private farmhouse. They have a working knowledge of Chhattisgarhi and can communicate with the local labourers on the farm. “We came here 20 years ago in search of rozi roti [livelihood],” says Lata. “All my family members stay in Odisha. Everyone speaks Odia, but my children cannot read or write in our language. They can only speak. At home we all do. Even I cannot read and write Odia. Speaking is all I know.” Priti, their youngest daughter, loves Hindi poetry, but hates being in school.

Shankar Das (left) after a decade and a half in Pune, can speak Marathi but cannot get a job in his home state, because he cannot speak Assamese. Priti Bhoi (centre) and her mother Lata Bhoi (right), are migrants from Orissa living in Chhattisgarh. Priti doesn't want to continue in her present school as she is being teased by her classmates

“I manage to speak in Chhattisgarhi with my classmates. But I no longer want to study here,” Priti says, “because my school friends tease me by calling me ‘Odia- Dhodia ’.” Dhodia in Chhattisgarhi refers to a species of non-venomous snakes, timid in nature. Her parents now want to send Priti to a government residential school in Odisha if they can secure a place for her under the Scheduled Tribe quota.

Being separated from one’s parents, land, and language at an early age is a story of almost every migrant’s life.

Nagendra Singh, 21, left home in search of rozgar when he was barely 8 years old and joined a crane operating service as a cleaner. Home was Jagadishpur village in Kushinagar district of Uttar Pradesh, where they spoke Bhojpuri. “It is quite different from Hindi,” he explains. “If we start talking in Bhojpuri you wouldn’t understand it.” His ‘we’ refers to three of his roommates and coworkers, painters at a construction site in north Bangalore. Ali, 26, Manish, 18, and Nagendra are separated by their age, village, religion, and caste, but united by their common mother tongue – Bhojpuri.

They left their homes and language behind in the villages when they were in their teens. “If you have skills, you have no problem,” says Ali “I have been to Delhi, Mumbai, Hyderabad, even Saudi Arabia. I can show you my passport. I picked up English and Hindi there.” The way it happens is quite simple, Nagendra joins the conversation to explain. “We go wherever there is work. Gaon ka koi ladka bula leta hai, hum aa jaate hai [some boy from our village will call us and we go],” he says.

“There are people like this uncle,” Nagendra points to a co-worker, 57-year-old Subramanium from Madurai, who knows only Tamil. “With him we use sign language. We want to tell him something we tell the carpenter and he conveys it to uncle. But amongst ourselves we speak Bhojpuri. When I go to the room in the evening, I cook my food and listen to Bhojpuri songs,” he says pulling out his mobile for us to listen to one of his favourites.

Nagendra Singh (left) and Abbas Ali (right), p ainters at a construction site in north Bangalore, may be separated by their age, village and religion but are united by the language they speak, Bhojpuri

Left: Subramaniam from Tamil Nadu and young Manish from Uttar Pradesh work together at a construction site in Bangalore as painters. They use sign language to communicate. Right: Nagendra Singh is eating the food he made himself . But he still misses the taste of his village in it

Familiar food, melodies, festivals, a fuzzy set of beliefs that we always associate with our culture often come to us as linguistic experiences. And so, when asked about their mother language, many of the people PARI spoke to slipped into conversations around culture.

More than two decades after he left Partapur, his village in Bihar, to work as a domestic helper in Mumbai, 39-year-old Basant Mukhiya’s mind overflows with memories of home food and songs at the first mention of Maithili. “I like sattu [flour made from roasted gram] a lot, and chura or poha ,” he says. He can get some of these in Mumbai, but it is not the same. Saying that “the taste of my village is missing,” Basant sets off on the culinary trail. “In our place every Saturday we eat khichdi for lunch and bhuja as evening snack. Bhuja is made with flattened rice, roasted peanuts, and roasted black gram mixed with onions, tomatoes, green chillies, salt, mustard oil and other spices. In Mumbai I do not even know when Saturday comes and goes,” he says with a wistful smile.

The other thing that comes to his mind is the way in which they played Holi in his village. “A group of friends would barge into your house without warning on that day. We would play with colours, wildly. And then there would be malpua (a special sweet made on Holi from semolina, maida , sugar, and milk) to devour. We would sing phagua , songs of Holi,” says Basant. The images of his native place come vividly alive even when he speaks to us in his non-native tongue.

“The pleasure of celebrating the festival with people who are from your own place and speak your language is something else,” he admits.

Raju, as he is liked to be called, who comes from Amilaouti village in Allahabad would agree entirely with Basant. He has been earning his livelihood in Punjab for the last 30 years now. A man from the Ahir community, he used to speak in Awadhi at home and struggled when he first came to Amritsar. “But today I am fluent in Punjabi and everyone loves me,” he says happily.

Basant Mukhiya, working as a domestic help in Mumbai for more than two decades, misses the sounds and songs of his village. His mind overflows with memories of home food at the first mention of his mother tongue, Maithili

Raju from Amilaouti in Allahabad sells fruits in Punjab’s Patti town and speaks fluent Punjabi. He misses the festivals they celebrated in his village

And yet, this fruit seller in Punjab’s Patti town in Tarn Taran district, does miss his festivals. The workload often stops him from visiting his village. "It’s impossible to celebrate my own festivals out here,” he says. “One can participate in the festival of 100 people, but tell me who will join if the festival is celebrated by merely two or four people?"

At the other end of the country, Shabana Sheikh, 38, who has come from Rajasthan to Kerala with her husband in search of work, asks the same question. “We celebrate our festivals in our village and there is no shame in doing it. But how can we celebrate them here in Kerala?” she asks. “During Diwali there are not very many lights in Kerala. But in Rajasthan we light clay lamps during the festival. It looks very beautiful,” she says. Her eyes lighting up with memories.

The relationship between language, culture, and memory is fairly knotted for each one of the migrants we spoke to. But living in homes away from home in remote places they have also found their own ways of keeping them alive.

Masharu Rabari in his 60s has no permanent address except somewhere on a field in either Nagpur, Wardha, Chandarapur, or Yavatmal. A pastoralist of central Vidarbha, he comes from Kachchh in Gujarat. “In a sense I am Varhadi,” he says, dressed in the typical Rabari costume – a gathered upper garment, a dhoti, and a white turban. He is entrenched in the local culture of Vidarbha, and can even let loose local expletives and slang when needed! And yet he has kept his ties with the traditions and culture of his land intact. Among his belongings stacked on the back of his camels as they move from field to field is a bundle full of folktales, inherited wisdom, songs, traditional knowledge about the animal world, ecology and more.

Left: Mashru Rabari from Kuchchh lives on the cotton fields of Vidarbha and calls himself a Varhadi. Right: Shabana Sheikh (extreme left) from Rajasthan and lives with her husband, Mohammed Alwar (right) and daughter Sania Sheikh (centre) in Kerala. She misses the Diwali lights of her village

An excavator operator from Jharkhand, Shanaulla Alam, 25, now lives in Udupi in Karnataka. He is the only one who speaks fluent Hindi at work. His only connection to his language and people is through his mobile phone, when he talks to his family and friends, speaking in Hindi or Khortha, a language spoken in North Chotanagpur and the Santhal Pargana of Jharkhand.

Another young migrant from Jharkhand, 23-year-old Sobin Yadav, also relies on his mobile to keep in touch with all that is familiar. He moved from Majgaon village, “about 200 kilometres from cricketer Dhoni’s house,” to Chennai some years ago. Working at an eatery in Chennai, he hardly gets to speak Hindi. He uses his mother language only when talking to his wife over the phone every evening. “I also watch Tamil films dubbed in Hindi on my mobile phone. Suriya is my favourite actor,” he says speaking in Tamil.

"Hindi, Urdu, Bhojpuri...no language will ever work here. Not even English. Only the language of the heart works," says Vinod Kumar. This 53-year-old mason from Bihar’s Motihari district is having lunch in Sajid Gani’s kitchen in Pattan block in Kashmir’s Baramulla district. Sajid is his local employer. "A homeowner eating beside a labourer – have you seen this anywhere else?” Vinod asks us, pointing at Sajid. “I don't think he even knows my caste. Back home, people won't even drink water if I had touched it, and here he is feeding me in his own kitchen and eating beside me.”

It is 30 years now since Vinod first came to Kashmir for work. "Back in 1993 I came to Kashmir for the first time as a labourer. I didn't have much idea about Kashmir. Media back then was not a thing like it is now. Even if newspapers carried some information, how was I supposed to know? I can neither read nor write. Whenever we got a call from a thekedar , we went to earn our bread,” he explains.

Left: Shanaulla Alam from Jharkhand works as an excavator operator in Udupi, Karnataka. He speaks in Hindi or Khortha over the phone when speaking to his family and friends. Right: Sobin Yadav, also from Jharkhand, speaks Tamil at the eatery where he works in Chennai and Hindi when speaking to his wife over the phone

“I had a job in Anantnag district then,” he says recalling his early days. “The day we reached everything had suddenly closed down. I was left jobless for quite a few days, without a paisa in my pocket. But the villagers out here helped me, all of us. There were 12 of us who had come together. They fed us. Tell me, who on earth helps like this without an ulterior motive?" he asks. Sajid tries to slide an extra piece of chicken on Vinod’s plate, ignoring his polite refusals, as he is speaking.

“I don't understand even a single word of Kashmiri,” Vinod continues. “But everybody understands Hindi out here. It has worked out fine so far."

“What about Bhojpuri [his mother tongue]?” we ask him.

“What about it?” he retorts. "When my fellow villagers arrive, we talk in Bhojpuri. But whom shall I speak in Bhojpuri over here? You tell me...?" he asks. And then he smiles and adds, "I have taught Sajidbhai a little bit of my mother-tongue. Ka ho Sajidbhai? Kaisan bani ? [Tell me Sajidbhai? How are you?]"

" Thik ba [I'm alright]," Sajid answers.

"A little mistake happens here and there. But come next time my bhai here will sing one of Ritesh’s [a Bhojpuri actor] songs for you!”

This story has been reported by

Md. Qamar Tabrez

from Delhi;

Smita Khator

from West Bengal;

Pratishthha Pandya

and

Shankar N. Kenchanur

from Karnataka;

Devesh

from Kashmir;

Rajasangeethan

from Tamil Nadu;

Nirmal Kumar Sahu

from Chhattisgarh;

Pankaj Das

from Assam;

Rajeeve Chelanat

from Kerala;

Jaideep Hardikar and Swarna Kanta

from Maharashtra;

Kamaljit Kaur

from Punjab; and edited by

Pratishthha Pandya

, with editorial support from

Medha Kale, Smita Khator, Joshua Bodhinetra

and Sanviti Iyer

. Photo editing by

Binaifer Bharucha.

Video editing by

Shreya Katyaini.

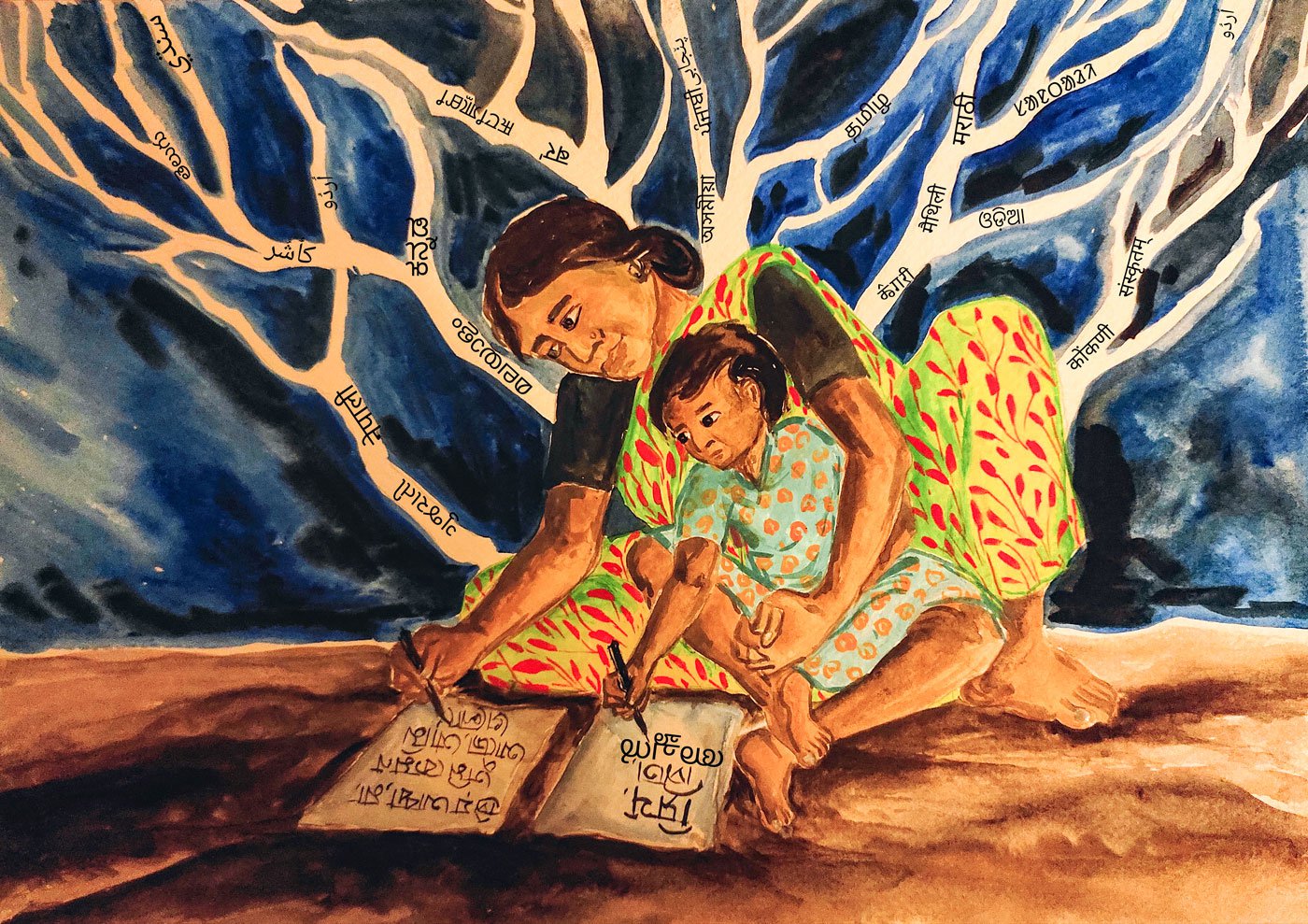

Cover illustration:

Labani Jangi