There were battles on other fronts, too, that Panimara's freedom fighters had to wage. Some of these were right at home.

Inspired by Gandhiji's call against untouchability, they acted.

"One day, we marched into our Jagannath temple in this village with 400 Dalits," says Chamaru. The Brahmins did not like it. But some of them supported us. Maybe they felt compelled to. Such was the mood of the times. The gauntiya (village chief) was managing trustee of the temple. He was outraged and left the village in protest. Yet, his own son joined us, supporting us and denouncing his father's action.

"The campaign against British goods was serious. We wore only khadi . We wove it ourselves. Ideology was a part of it. We actually were very poor, so it was good for us."

All the freedom fighters stuck to this practice for decades afterwards. Until their fingers could no longer spin or weave. "At 90, last year," says Chamaru, “I thought it was time to stop."

It all started with a Congress-inspired "training" camp held in Sambalpur in the 1930s. "This training was called ` sewa ' [service] but instead we were taught about life in jail. About cleaning toilets there, about the miserable food. We all knew what the training was really for. Nine of us went from the village to this camp.

"We were seen off by the entire village, with garlands and

sindhur

and

fruit. There was that kind of sense of ferment and significance."

There was also, in the background, the magic of the Mahatma. "His letter calling people to satyagraha electrified us. Here we were, being told that us poor, illiterate people, could act in defiance, to change our world. But we were also pledged to non-violence, to a code of conduct." A code most of the freedom fighters of Panimara lived by for the rest of their lives.

They had never seen Gandhiji then. But like millions of others, were moved by his call. "We were inspired here by Congress leaders like Manmohan Choudhary and Dayanand Satpathy." Panimara's fighters made their first trip to jail even before August 1942. “We had taken a vow. Any kind of cooperation with the war [World War II] in money or in person, was a betrayal. A sin. War had to be protested by all non-violent means. Everybody in this village supported this.

"We went to jail in Cuttack for six weeks. The British were not keeping people imprisoned for long. Mainly because there were thousands cramming into their jails. There were just too many people willing to be jailed."

Jitendra Pradhan, 81, and others singing one of Gandhi's favourite bhajans

The anti-untouchability campaign threw up the first internal pressures. But these were overcome. "Even today," says Dayanidhi, "we don't use Brahmins for most of our rituals. That temple entry' upset some of them. Though, of course, most felt compelled to join us in the Quit India movement."

Caste exerted other pressures, too. "Each time we came out of jail," says Madan Bhoi, "relatives in nearby villages wanted us to be `purified'. This was because we had been in prison with untouchables." (This "purification" of caste prisoners goes on in rural Orissa, even today: PS).

"When I returned from jail once," says Bhoi, "it was the 11th day ceremony for my maternal grandmother. She had died while I was inside jail. My uncle asked me, `Madan, have you been purified?' I said no, we purify others by our actions as satyagrahis . I was then seated separately from the rest of the family. I was isolated and ate alone.

"My marriage had been fixed before I went to jail. When I came out, it was cancelled. The girl's father did not want a jailbird for a son-in-law. Finally, though, I found a bride from Sarandapalli, a village where the Congress had great influence."

* * *

Chamaru, Jitendra and Purnachandra had no problems of purity at all during their prison stay in August 1942.

"They sent us to a prison for criminals. We made the most of it," says Jitendra. "In those days, the British were trying to recruit soldiers to die in their war against Germany. So they held out promises to those who were serving long sentences as criminals. Those who signed up for the war would be given Rs. 100. Each of their families would get Rs. 500. And they would be free after the war.

"We campaigned with the criminal prisoners. Is it worth dying for Rs. 500 for these people and their wars? You will surely be amongst the first to die, we told them. You are not important for them. Why should you be their cannon fodder?

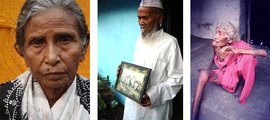

Showing a visitor the full list of Panimara's fighters

"After a while, they began to listen to us. [They used to call us Gandhi, or simply, Congress]. Many of them dropped out of the scheme. They rebelled and refused to go. The warden was most unhappy. `Why have you dissuaded them?' he asked. `They were ready to go till now’. We told him that, in retrospect, we were happy to have been placed amongst the criminals. We were able to make them see the truth of what was going on.

"The next day we were transferred to a jail for political prisoners. Our sentence was changed to six months of simple imprisonment.”

* * *

What was the injustice of the British Raj that provoked them to confront so mighty an empire?

"Ask me what was the justice in the British Raj," says Chamaru with gentle derision. That was not a smart question to have put to him. "Everything about it was injustice.

"We were the slaves of the British. They destroyed our economy. Our people had no rights. Our agriculture was ruined. People were reduced to terrible poverty. Between July and September 1942 only five or seven of the 400 families here had enough to eat. The rest braved hunger and humiliation.

"The present rulers too, are pretty shameless. They loot the poor as well. Mind you, I won't equate anything to the British Raj, though. But our present lot are also awful.”

* * *

Panimara’s freedom fighters still go to the Jagannath temple every morning. Where they beat the nissan (drum) as they have since 1942. At an early hour, it can be heard for a couple of kilometres around, they say.

But on Fridays, the freedom fighters try to gather at 5.17 p.m. Because "it was Friday that the Mahatma was murdered." At 5.17 p.m. It's a tradition this village has kept alive for 54 years.

It's a Friday today, and we accompany them to the temple. Four of the seven living freedom fighters are present. Chamaru, Dayanidhi, Madan and Jitendra. Three others, Chaitanya, Chandrashekar Sahu and Chandrashekar Parida, are out of the village just now.

The last living fighters in Panimara at their daily prayers

The foyer of the temple is packed with people, who sing a

bhajan

favoured by Gandhi. "In 1948," says Chamaru, "many in this village shaved their heads when the news of the Mahatma's murder came. They felt they had lost their father. And to this day, many fast on Fridays."

May be some of the children are here in the little temple out of curiosity. But this is a village with a sense of its history. With a sense of its own heroism. One that feels a duty to keep the flame of freedom alive.

Panimara is a village of small cultivators. "There were around 100 Kulta (cultivator caste) families. About 80 Oriya (also cultivators). Close to 50 Saura Adivasi households, 10 goldsmith caste families. Some Goud (Yadav) families and so on," says Dayanidhi.

That, broadly, remains the village’s occupation. Most of the freedom fighters were members of the cultivator castes. "True, we have not had too many inter-caste marriages. But relations between the groups have always been fine since the days of the freedom struggle. The temple is still open to all. The rights of all are respected."

There are a few who feel some of their rights have not been recognised. Dibitya Bhoi is one of them. "I was very young and I was badly thrashed by the British," he says. Bhoi was then 13. But since he was not sent to prison, his name did not make it to the official list of freedom fighters. Some others were also badly beaten up by the British but ignored in the official record because they did not go to prison.

That colours the names on the stambh or pillar to commemorate the freedom fighters. Only the names of those who went to jail in 1942 are there. But no one disputes their right to be there. Just sadly, the way the official recording of "freedom fighters" went, it left out others who also deserved recognition.

August 2002, 60 years later, and Panimara's freedom fighters are at it again.

This time Madan Bhoi – the poorest of the seven, owning just over half an acre of land – and his friends are sitting on a dharna . This is just outside the Sohela telephone office. "Imagine," says Bhoi, "after all these decades, this village of ours does not have a telephone."

So on that demand, “we sat on a dharna . The SDO [sub-divisional officer] said he had never heard of our village," he laughs. "This is blasphemy if you live in Bargarh. This time, funnily, the police intervened."

The police, who knew these men as living legends, marvelled at the SDO's ignorance. And were quite worried about the condition of the 80-year-olds. "In fact, after hours of the dharna , the police, a doctor, medical staff and others intervened. Then the telephone people promised us an instrument by September 15. Let us see."

Once again, Panimara's fighters were struggling for others. Not for themselves. What did they ever get out of their struggles for themselves?

"Freedom," says Chamaru.

For you and me.

This article (the second of two parts) originally appeared in The Hindu Sunday Magazine on October 27, 2002. The first part appeared on October 20, 2002.

Photos: P. Sainath

More in

this series

here:

Panimara's foot soldiers of freedom - 1

The last battle of Laxmi Panda

Sherpur: big sacrifice, short memory

Godavari: and the police still await an attack

Sonakhan: when Veer Narayan Singh died twice