“Take back all these petitions and tear them up," said Chamaru. "They are not valid. This court will not entertain them."

He was really beginning to enjoy being a magistrate.

It was August 1942 and the

country was in ferment. The court in Sambalpur certainly was. Chamaru Parida

and his comrades had just captured it. Chamaru had declared himself the judge.

Jitendra Pradhan was his "orderly." Purnachandra Pradhan had opted to

be a

peshkar

or court clerk.

The capture of the court was part of their contribution to the Quit India movement.

"These petitions are addressed to the Raj," Chamaru told the astonished gathering in the court. "We live in free India. If you want these cases considered, take them back. Re-do your petitions. Address them to Mahatma Gandhi and we'll give them due attention."

Sixty years later, almost to the day, Chamaru still tells the story with delight. He is now 91 years old. Jitendra, 81, is seated beside him. Purnachandra, though, is no more. They still live in Panimara village in Odisha’s Bargarh district. At the height of the freedom struggle, this village sent a surprising number of its sons and daughters to battle. The records show that in 1942 alone, 32 people from here went to prison. Seven of them are still alive, including Chamaru and Jitendra.

At one point, nearly every family here sent out a satyagrahi . It was a village that vexed the Raj. Its unity seemed unshakeable. Its determination grew to be legendary. Those confronting the Raj were poor, unlettered peasants. Smallholders struggling to make ends meet. Most remain that way.

Never mind that the history books make almost no mention of them. Nor that they might even be forgotten in much of Odisha itself. In Bargarh, this is still Freedom Village. Very few, if any, gained personally from their struggle. Certainly not in terms of rewards, posts or careers. But they took the risks. These were people who fought for India's Independence.

These were the foot soldiers of freedom. Barefoot ones at that. Nobody here ever had shoes to wear, anyway.

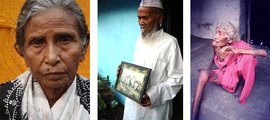

Seated left to right: Dayanidhi Nayak, 81, Chamuru Parida, 91, Jitendra Pradhan, 81, and (behind) Madan Bhoi, 80, four of seven freedom fighters of Panimara village still alive

"The police in the court were baffled," chuckles Chamaru. "They were not quite sure about what to do. When they tried arresting us, I said, I am the magistrate. You take orders from me. If you are Indians, obey me. If you are British, go back to your own country’."

The police then went to the real magistrate who was in his residence that day. "The magistrate refused to sign orders for our arrest because the police had no names on the warrants," says Jitendra Pradhan. "The police returned and sought our names. We refused to tell them who we were."

A bewildered police squad went to the collector, Sambalpur. "He, apparently finding the farce tiring, told them, `Simply put in some names. Call the fellows A', B' and C' and fill in the forms accordingly’. So the police did that, and we were arrested as criminals A, B and C," says Chamaru.

It remained a trying day for the police, though. "At the prison," laughs Chamaru, "the warden would not accept us. An argument raged between him and the police. The warden asked them: Do you think I am stupid? What will happen if these fellows escape or abscond tomorrow? Will I report that A, B and C have escaped? A fine idiot I would look, doing that’. He was adamant."

After hours of haggling, the police got prison security to accept the men. "It was when we were produced in court that the farce reached its peak," says Jitendra. "The embarrassed orderly had to shout: A, haazir ho ! B, haazir ho ! C, haazir ho ! [A, B and C, present yourselves]’. And the court then dealt with us."

The system avenged itself for the embarrassment. They were given six months rigorous imprisonment and sent to a prison for criminals. "Normally, they would have sent us to those places where they held their political prisoners," says Chamaru. "But this was the height of the agitation. And anyway, the police were always cruel and vindictive.

"There was no bridge across the Mahanadi those days. They had to take us in a boat. They knew we had courted arrest and had no intentions of escaping. Yet, they tied our hands and we were tied to each other. If the boat had capsized – and such things happened frequently – we stood no chance. We would all have died.

"The police went after our families, too. Once, I was in jail and had also been sentenced to a fine of Rs. 30 [A huge sum in a time when they earned two annas worth of grain working the whole day: PS]. They went to collect the fine from my mother. Pay or he'll get a bigger sentence’," they warned.

The stambh or pillar honouring the 32 ‘officially recorded’ freedom fighters of Panimara

"My mother said: He's

not my son; he's the son of this village. He cares more for this village than

for me’. They still pressed her. She said: `All the youth of this village are

my sons. Will I pay for all those in jail?'"

The police were frustrated. "They said: Well, give us something we can show as a seizure. A sickle or something’. She simply said: `We don't have a sickle’. And she began to collect gobar pani and told them she intended cleaning the place where they were standing so as to purify it. Would they please leave?" They did.

* * *

While the courtroom farce was on, Squad Two of Panimara's satyagrahis was busy. "Our task was to capture the Sambalpur market and destroy British goods," says Dayanidhi Nayak. He is Chamaru's nephew and "I looked up to him for leadership. My mother died in childbirth and I was brought up by Chamaru."

Dayanidhi himself was just about 11 when he had the first of his run-ins with the Raj. By 1942, at 21, he was practically a seasoned fighter. Now 81, Dayanidhi recalls every detail of those days with clarity.

"There was tremendous anti-British feeling. The attempts by the Raj to intimidate us made it stronger. They had their armed troops surround this village, more than once, and conduct flag marches. Just to scare us. It didn't work.

"The anti-Raj feeling cut across all lines. From landless workers to school teachers. The teachers were with the movement. They did not resign, they just didn't work. And they had a great excuse. They said: `How can we give them our resignations? We don't recognise the British’. So they went on, not working!

"We were an even more cut-off village in those days. Because of arrests and crackdowns, Congress activists didn't come for some days. That meant we had no news of the outside world. That's how it was in August 1942." So the village sent out people to learn about what was going on. "That's how this phase of action began. I was with Squad Two.

"All five of our group were very young. First, we went to Congressman Fakira Behera's house in Sambalpur. We were given flowers and an arm band saying `Do or Die’. We marched to the marketplace with lots of school children and others running alongside.

"At the marketplace, we read out the Quit India call. There were over 30 armed police who arrested us the moment we read the call.

"Here, too, there was confusion and they immediately let some of us go."

Why?

At the temple, the last living fighters in Panimara

"Oh well, it was ridiculous for them to arrest and tie up 11 year olds. So those of us who were that young, below 12, were let off. But two little ones, Jugeshwar Jena and Inderjeet Pradhan, would not leave. They wanted to remain with the group and had to be persuaded to go. The rest of us were sent to Bargarh jail. Dibya Sunder Sahu, Prabhakara Sahu and I went on to serve nine months there."

* * *

Madan Bhoi, 80, still sings a fine song in a clear voice. "It's the song that the third group from our village sang as we marched to the Congress office in Sambalpur." The British had sealed that office citing seditious activity.

Squad Three's aim: to liberate the sealed Congress office.

"My parents had died while I was very young. The uncle and aunt I lived with didn't care much for me. They grew alarmed when I attended Congress meetings. When I tried to join the satyagrahis , they locked me in a room. I pretended to repent and reform. They let me out. I went to the fields as if to work. With my hoe, basket and the rest. From the fields I went off to the Bargarh satyagraha . I joined 13 others from our village there, ready for the march to Sambalpur. I didn't even have a shirt of any kind, let alone khadi . Though Gandhi had been arrested on August 9, news of it reached this village days later. That was when this plan of sending three or four squads of protestors out to Sambalpur came up, you see.

"The first batch had been arrested on August 22. We were arrested on August 23. The police did not even take us to court fearing the kind of embarrassment they'd been subjected to by Chamaru and his friends. We were never allowed to reach the Congress office. We went straight to jail."

Panimara was now notorious. "We were widely known," says Bhoi with some pride, "as the badmash gaon [rogue village]."

Photos: P. Sainath

This article originally appeared in The Hindu Sunday Magazine on October 20, 2002.

More in

this series

here:

Panimara's footsoldiers of freedom - 2

The last battle of Laxmi Panda

Sherpur: big sacrifice, short memory

Godavari: and the police still await an attack

Sonakhan: when Veer Narayan Singh died twice