PARI Library bulletin on India’s classrooms

ମୁଖ୍ୟ ଆକର୍ଷଣ

The PARI Library draws attention to what research on rural education is telling us. Using data and anecdotes from ground reportage, we get a ringside view of the education system and how policies and laws are enacted on the ground

If you are a child in the age group of 6-14 years, you have the right to “free and compulsory education” at your neighbourhood schools. The law deciding this – The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act (RTE) was enacted by the Government of India in 2009.

But nine-year-old Chandrika Behera in Odisha’s Jajpur district has been out of school for almost two years now as the nearest school is still too far – some 3.5 kms away from her home.

Teaching and learning practices in rural India are not consistent, and laws and policies are often only on paper. In at least some cases, systemic challenges are overcome by innovation and tenacity of the individual teacher who is more often than not, making a real difference.

Take, for instance, the travelling teacher in Kashmir’s Anantnag district who moves for four months into a Gujjar settlement in Lidder valley to teach young children from this nomadic community. Teachers are also trying innovative practices to best use their limited resources. Like the teachers at Coimbatore’s Vidya Vanam School who have got their students to debate on genetically modified crops. Many of them are first-generation English speakers but they are debating in English, laying out the value of organic rice and more.

Step into classrooms, get a ringside view of learning outcomes and a better picture of the state of education in India with a visit to the PARI Library. We bring reports on access, quality and gaps in rural education. Each document in the Library carries with it a short summary which highlights the major takeaways.

The latest Annual Status of Education (Rural) report states that in 2022, children’s basic reading ability has dropped to pre-2012 levels – in both private and government schools across the country. In the Toranmal region of Maharashtra’s Nandurbar district, 8-year-old Sharmila taught herself to wield a sewing machine after her school closed in March 2020. Referring to Marathi alphabets, she says, “ I don’t remember them all ”.

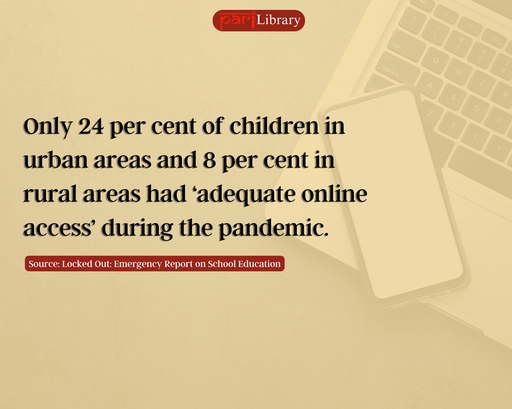

The covid-19 pandemic led to a surge in the education crisis across states. Those anyway struggling to secure an education were pushed beyond its fringes with the shift towards online education – only 24 per cent of children in urban areas and eight per cent in rural areas had ‘adequate online access,’ shows this survey conducted in August 2021.

Mid-day meals provided in schools to students between Classes 1-8 cover about 11.80 crore children. About 50 per cent of students in rural areas reported receiving free mid-day meals in their schools – 99.1 per cent of them were enrolled in government institutions. “Few parents can afford this lunch for their children,” says headmistress Poonam Jadhav from the Government Primary School in Chhattisgarh's Matia village. The need to consistently strengthen such welfare schemes in schools is evident.

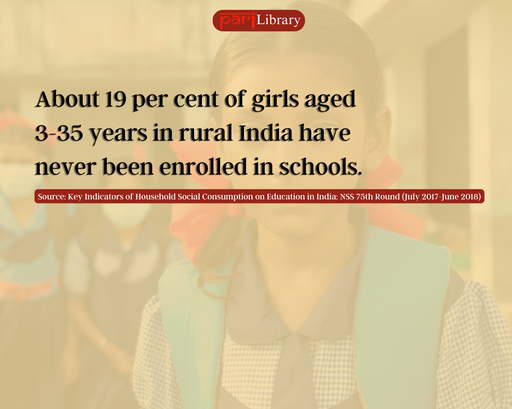

“My father says I’ve studied enough. He says if I keep studying, who will marry me?” says Shivani Kumar, 19, from Bihar’s Samastipur district. Gender is a big marker in education – girls often rank lower in the scale of resource allocation. Key Indicators of Household Social Consumption on Education in India: NSS 75th Round (July 2017-June 2018) confirms this. About 19 per cent of girls aged 3-35 years in rural India have never been enrolled in schools, the report says.

Of the 4.13 crore students enrolled in higher education in India in 2020, only 5.8 per cent were from Scheduled Tribes. This reveals the disproportionate access to education between social groups in India. “In rural areas, an increase in the number of private schools appears to have simply maintained the social, economic, and demographic status quo instead of opening new opportunities for India’s marginalised communities,” states a report by Oxfam India.

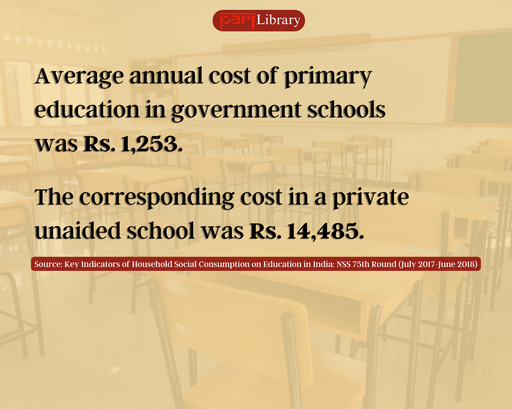

Despite a shift toward private schools, many continue to rely on government support for their education. The reasons are obvious – while the average annual cost of education at the primary level was Rs. 1,253 in government schools, the corresponding cost in a private unaided school was Rs. 14,485. “Private school teachers think that all we do is cook and clean. I don’t have ‘experience’ in teaching according to them,” 40-year-old Rajeshwari says, who is a teacher at an anganwadi in Bengaluru.

The lack of basic infrastructure like drinking water and toilets makes the work of school teachers like Rajeshwari tedious and difficult. Take, for instance, the zilla parishad primary school in Sanja village, Osmanabad. Since March 2017, this school in Maharashtra has not had any electricity. "The funds coming from the government are not enough… we get only 10,000 rupees per year for school maintenance and to buy stationery for students," says Sheela Kulkarni, the principal of the school.

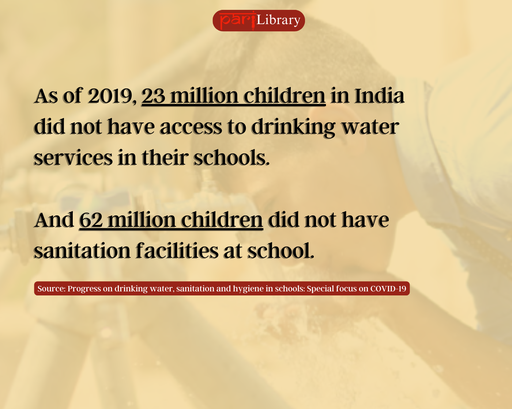

This is not rare – as of 2019, as many as 23 million children India did not have access to drinking water services in their schools and 62 million children did not have sanitation facilities at school.

Rural education is not simply a tale of deprivation as the growing number of colleges in India shows: an increase from 42,343 in 2019-20 to 43,796 in 2020-21, as per the All India Survey of Higher Education. There were 4,375 colleges exclusively for girls in the country during this period.

In villages and small towns across the country, girls rebelled to have a chance at higher education. Jamuna Solanke from a hamlet in Maharashtra's Buldana district became the first girl in her Nathjogi nomadic community to pass Class 10. “People say I should become a bus conductor or an anganwadi worker because I will get a job quickly. But I will become what I want to become,” Jamuna insists.

Cover design: Swadesha Sharma

ଲେଖକ

PARI Library

କପିରାଇଟ୍

PARI Library

ପ୍ରକାଶନ ତାରିଖ

08 ସେପ୍ଟେମ୍ବର, 2023