Not quite 10 years old, Ejaz, Imran, Yasir and Shamima have only had a few years of school. Every year, they miss classes for up to four months while they migrate with their parents, falling behind on crucial primary schooling – lessons in basic mathematics, science and social studies, along with vocabulary and writing skills.

By the time the kids are 10, that would add up to a whole year out of the classroom. For even the best frontbenchers that is a formidable loss, difficult to overcome.

But

not anymore. Hot on their heels, moving with them as they migrate away from

school, is travelling teacher, Ali Mohammed. This is the third year that

25-year-old Ali has come up the mountains to Khalan, a Gujjar settlement in

Lidder valley, Kashmir and for the next four months of summer (June to

September), he will be up here teaching young children of Gujjar families who

have migrated with their animals in search of summer grazing grounds.

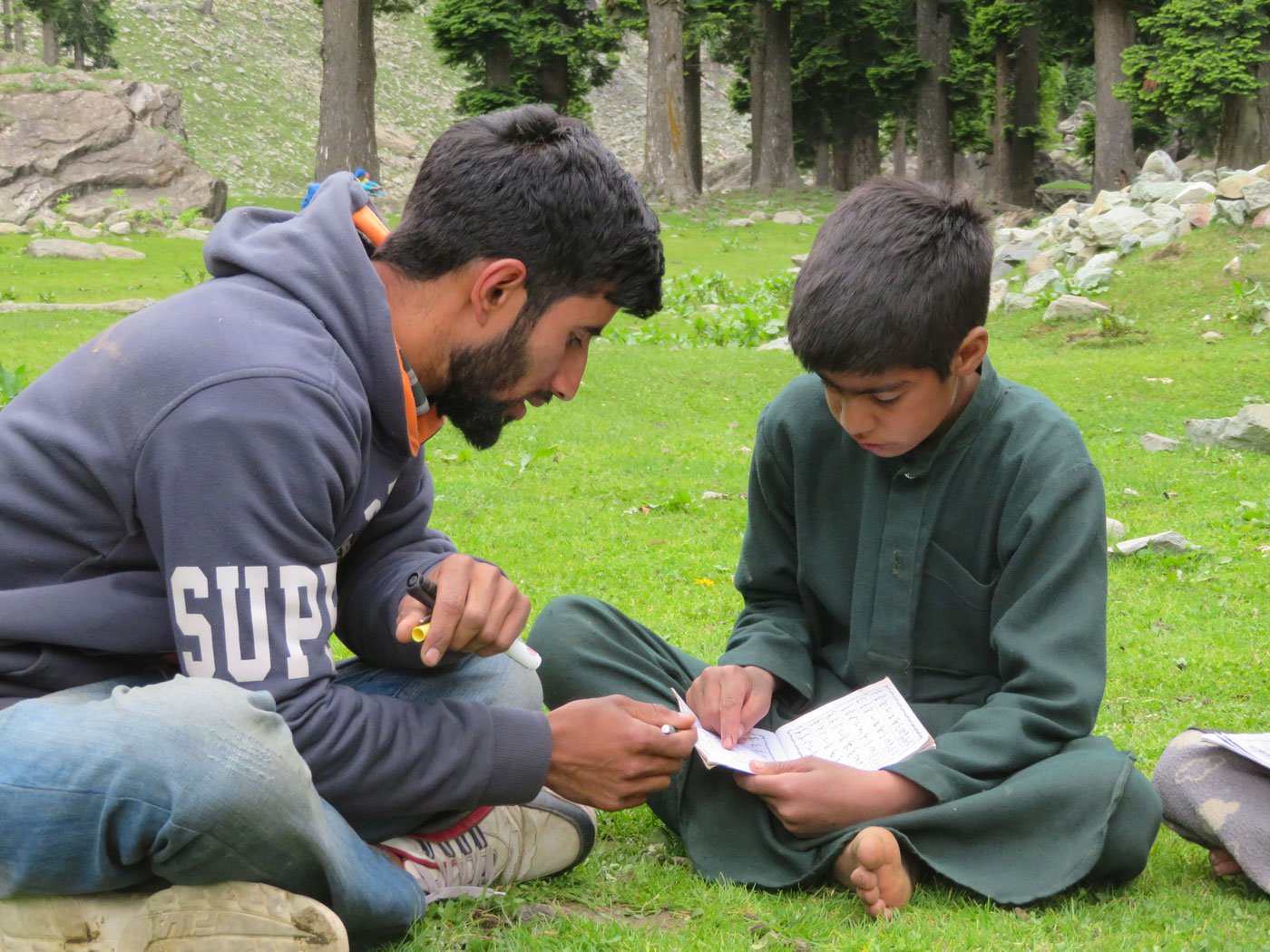

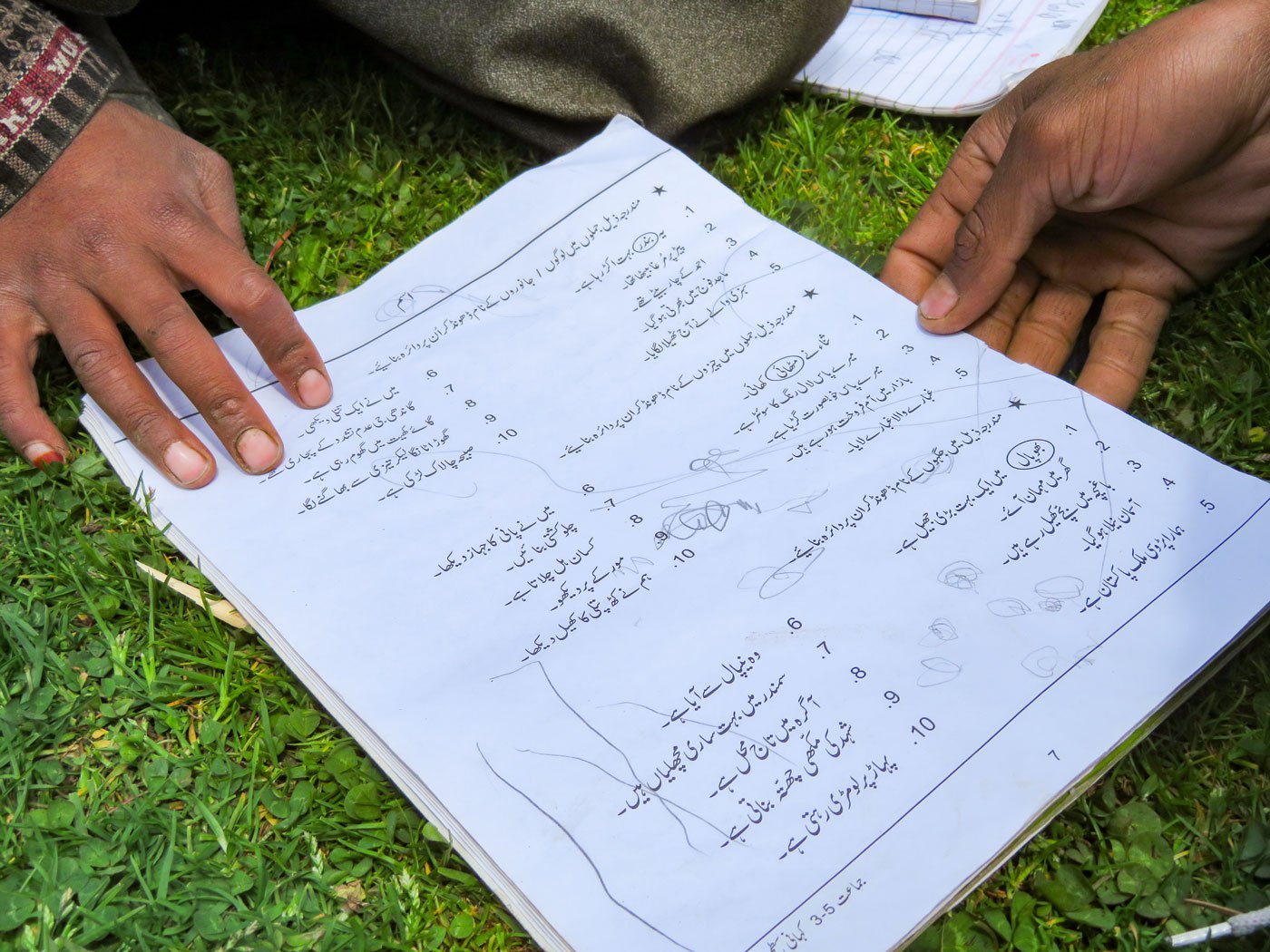

Left: Shamima Jaan wants to be a teacher when she grows up. Right: Ali Mohammed explaining the lesson to Ejaz. Both students have migrated with their parents to Khalan, a hamlet in Lidder valley

The Gujjar children (from left) Ejaz, Imran, Yasir, Shamima and Arif (behind) will rejoin their classmates back in school in Anantnag district when they descend with their parents and animals

A pastoralist community, Gujjars usually keep cattle and sometimes goat and sheep as well. Every year they ascend the Himalayas in summer in search of better grazing grounds for their livestock. This annual migration once meant skipping school for the young, leaving them with a shaky academic foundation.

But teachers like Ali who travel with them, are making sure that doesn’t happen and all truants are accounted for. “Some years ago, our community’s literacy rate used to be very low. Few people went to school as we would come up here to the high mountains where there was no chance to continue schooling,” says the young teacher, who once travelled like this with his Gujjar parents when he was young.

“But now with this scheme, these children are getting a teacher. They will stay engaged with their school work and our community will prosper,” he adds. “If not for this, these children who stay here for four months lag behind their counterparts down in the village school [in Anantnag district].”

Ali is referring to the central government’s Samagra Shisksha that was launched in 2018-19 and "subsumes the three schemes of Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA) and Teacher Education (TE)". It was meant to improve "school effectiveness measured in terms of equal opportunities for schooling and equitable learning outcomes."

So the school is a green tent on the banks of the rushing Lidder river in Pahalgam tehsil of Anantnag district. But on such a sunny day, the wide open meadows work as a classroom for this school master. Ali has a bachelor’s degree in Biology, and was given three months of training for this job. “We were shown what learning outcomes we should aim for, how to teach, and real life applications of what students’ learn.”

Ali

Mohammed (left) is a travelling teacher who will stay for four months up in the mountains, making sure his students are up to date with academic requirements. The wide open meadows of Lidder valley are much sought after by pastoralists in their annual migration

Class is in session on this warm June morning – Ali is sitting on the grass, surrounded by children ages 5-10 years. In an hour it will be 12 noon and he will wind up class here in Khalan, a hamlet of three Gujjar families. The mud plastered homes are situated at a slight elevation, a short distance from the river. Most of the handful of residents are outdoors, enjoying the weather, catching up with passersby. The families here have a total of 20 cows and buffaloes, and 50 goats and sheep, the children tell PARI.

“The school term began late as the place was under snow. I came up 10 days ago [June 12, 2023],” he says.

Khalan lies on the route to the Lidder glacier, another 15 kilometres uphill, at a height of roughly 4,000 metres – a place that Ali has visited with young men from the settlement. The area all around is lush and green with plenty of grazing for animals and both Gujjar and Bakarwal families are already settled at places along the river.

“I go to teach those children in the afternoon,” he says, pointing across the river to Salar, a hamlet of four Gujjar families. Ali will have to cross the furiously rushing waters on a wooden bridge to get to the other side.

Left: Ali with the mud homes of the Gujjars in Khalan settlement behind him. Right: Ajeeba Aman, the

50-year-old father of student Ejaz is happy his sons and other children are not missing school

Left: The Lidder river with the Salar settlement on the other side. The green tent is the school tent. Right:

Ali

and two students crossing the Lidder river on the wooden bridge. He will teach here in the afternoon

Locals say that originally there was only one school for both hamlets, but a couple of years ago a woman slipped on the bridge, fell into the water and died. After that, government rules kicked in and primary school children were not allowed to cross for school, instead the teacher had to. “So now I teach two shifts, since the last two summers,” he explains.

Since the earlier bridge was swept away, Ali has to take the one almost a kilometre downstream. Today his pupils from the other side are already waiting to escort him!

Each travelling teacher like Ali has a contract for four months, and earns roughly Rs. 50,000 for the entire period. He stays in Salar through the week. “My stay and meals I have to take care of, so I stay with relatives here,” he explains. “I am a Gujjar and these are my relatives. My cousin lives here and I stay with his family.”

Ali’s home is in Hilan village of Anantnag district, roughly 40 kilometres away. He sees his wife, Noorjehan and their child on weekends, when he heads down. His wife is also a teacher, and she takes tuitions in and around their home. “I have been interested in teaching since I was a young child.”

“The government has done a good thing and I am happy to be part of this, helping to educate my community’s children,” he says as he moves towards the wooden bridge across the river.

Ajeeba Aman, the 50-year-old father of young student Ejaz is also happy, “My son, my brother’s sons, all study now. It’s good that our children are getting a chance.”