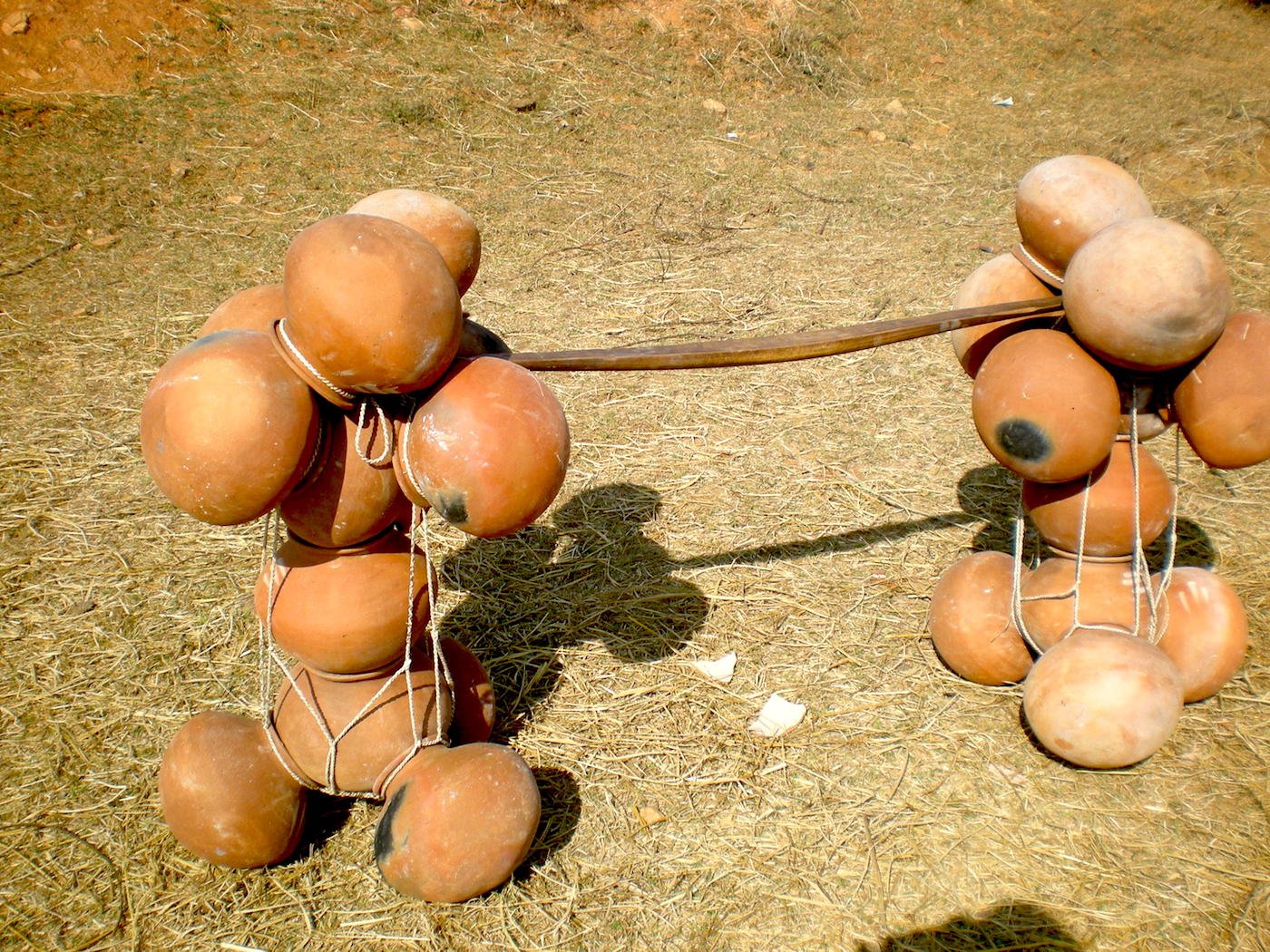

Madhav Naik of Baphla village in

Thuamul Rampur block of Kalahandi district is ready to go the weekly market at Adri

gram panchayat

. He carries

25 to 30 pots at a time; each weighs between 1 to 2 kilos.

It will be a two-hour journey across 12 kilometres. The road is rocky, and he will stop a few times to rest along the way. Every year, Naik manages to make between

Rs. 10,000-15,000 by selling these pots

.

Sobhini Muduli and Sundri Naik

on their way to the market at Adri. Pottery is strenuous work, and women and children do most of the labour. The clay is first beaten with a stick to make it even, then sieved to get rid of stones and other unwanted material. Then it is soaked in a water pit for half-a-day, then stomped on by foot to remove air bubbles.

Hari Majhi

at work: men generally helm the wheel. Pottery is an art which is passed on over generations

. It has an important role in Adivasi rituals and ceremonies, and the physical handling of the pots is believed to be a source of emotional and spiritual awareness. But the potters of the Kumbhar community in Kalahandi are slowly leaving their traditional occupation. “We can’t depend only on earthen pots for a livelihood,” says Gurunath Majhi of Baphla village. “There is no income, so we are also selling other household articles to survive.”

The clay is centred on a locally-made spinning wheel. A depression in the centre forms ‘walls’; these are drawn up by hand and shaped into the desired form. Water is kept nearby in a half-broken earthen bucket. A piece of old cotton cloth is used for applying water to the clay during the final shaping process.

Manglu Muduli (first from left) and Sukbaru Majhi

using a ‘pitani’ – a small round wooden beater – to give the final shape to the pots. Since this is done at the final stage, the potters are very careful about not making any mistakes

Hari Dhangdamajhi is an expert in moulding and shaping the earth. “I have seen my grandfather and father making earthen articles,” he says. “From an early age, I learned many techniques of pot making. But I don’t want my son to do this work for his survival. The demand for earthen pots has been going down day by day. Now we have to wait for local festivals, when we can earn a bit more.”

This steep decline in demand has forced the Kumbhars to also sell h

ousehold utensils made of aluminium and steel. Some double up as agricultural labourers, others migrate seasonally within the state or beyond.

A round-shaped traditional kiln is built in the courtyard. Clay items are bisque-fired for 2-3 hours. Before making the kiln, the women in the family collect the fuel – ‘kathokoila’ or charcoal, paddy straw and dry grass.

The pots are ready for sale. The price depends on the size and the season. In summers, the demand is relatively high and the potters of Baphla can hope to sell each pot for Rs. 50 to Rs. 80.

Till some years ago, pot-making was somewhat more lucrative in Kalahandi. But now the buyers are few. “It was common in the past to drink water stored in earthen pots, but this practice has nearly stopped because of coolers and bottled refills,” says Srinibash Das, who works with a non-governmental organisation in the region. “Though the pots are eco-friendly, there is not much demand for them now.”