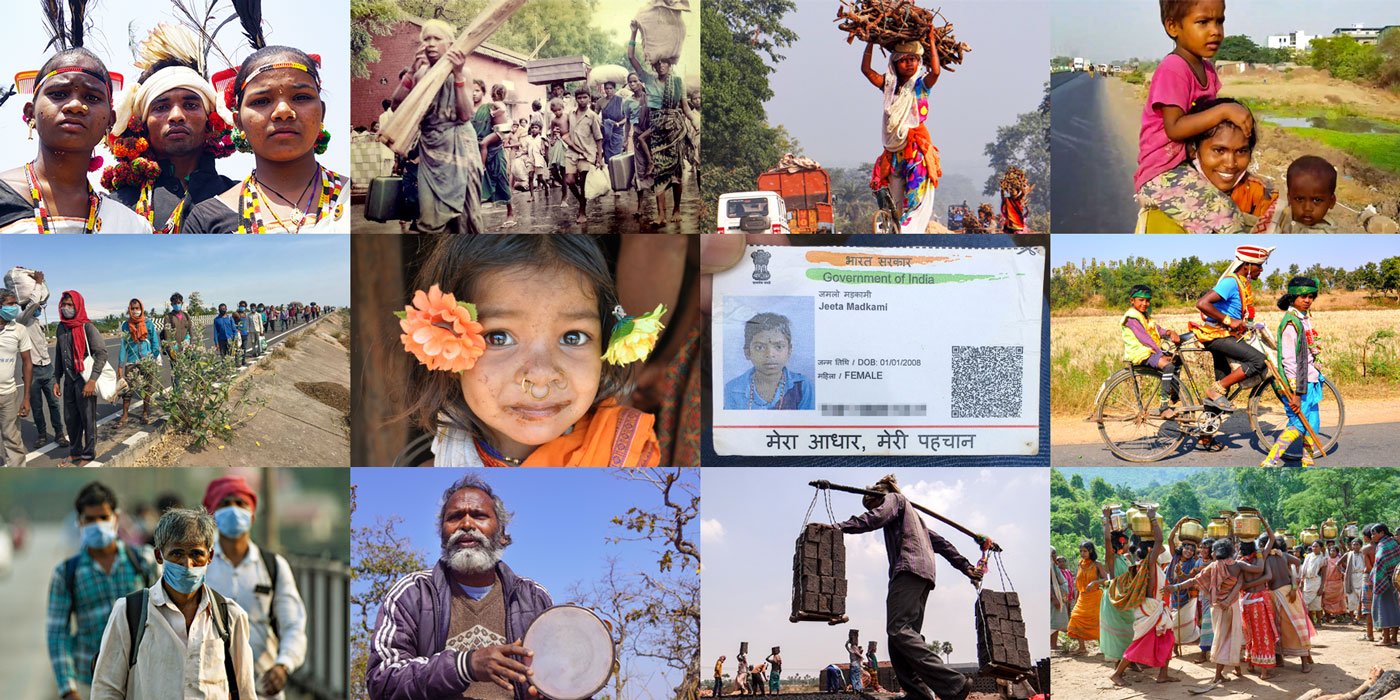

I was born in the undivided Kalahandi district, where drought, starvation, hunger-driven deaths and distress migrations were an integral part of people’s lives. As a young boy and later as a journalist, I witnessed and reported these matters vividly and rigorously. So I have an understanding of why people migrate, who migrates, what conditions force them to migrate, how they earn their livelihood – working way beyond their physical strength.

It was also ‘normal’ that when they were most in need of government support, they were abandoned. Without food, without water, without transport and compelled to walk hundreds of kilometres to distant places – many of them without even a pair of chappals.

It hurts me, since I have an emotional alignment, a connection with the people here – as if I were one of them. For me, they are certainly my people. So I was badly disturbed and felt helpless seeing the same people, the same communities, take yet another beating. That provoked me – and I am no poet - to pen these words and verse.

I am no poet

I am a photographer

I have photographed young boys

with headdresses, and

ghungroos

garlands around their neck.

I have seen boys

full of merry exuberance

cycling away on these same roads

where they are fire-walking home now.

Fire in the belly

Fire under their feet

Fire in their eyes

They walk on hot embers

scorching the soles of their feet.

I have photographed little girls

with flowers in their hair

And eyes smiling like water

Those, who had eyes

like my daughter’s –

are these the same girls

who now cry for water

with their smiles

drowning in their tears?

Who is this dying by the roadside

So close to my home?

Is this Jamlo?

Was that Jamlo I saw

leaping about barefoot

in green red chilli fields,

plucking, sorting, counting chillies

like numbers?

Whose hungry child is this?

Whose body is melting,

wilting by the roadside?

I have photographed women

young and old

Dongria Kondh women

Banjara women

Women dancing with brass pots

on their heads

Women dancing with joy

in their feet

These are not those women –

their shoulders droop

what loads they carry!

No, no, these cannot be

Gond women with

headloads of firewood

briskly walking on the highway.

These are half-dead, hungry women

With one cranky child on her hip

and the other without hopes inside her.

Yes, I know, they look

like my mother and sister

But these are malnourished, exploited women.

These are women waiting to die.

These are not those women

They may look like them –

but they are not the ones

I photographed

I have photographed men

resilient, feisty men

A fisherman, a labourer in Dhinkia

I have heard his songs

drive giant corporations away

This is not him wailing, is it?

Do I even know this young man,

that old man?

Walking miles and miles

Ignoring the misery chasing them

to drive growing loneliness away

Who walks so long

to escape gloom?

Who walks so hard

to fight the raging tears?

Are these men related to me?

Is he Degu

finally fleeing from the brick kiln

wanting to go home?

Do I photograph them?

Do I ask them to sing?

No, I am no poet

I cannot write a song.

I am a photographer

But these are not the people

I photograph.

Are they?

The author would like to acknowledge Pratishtha Pandya for her valuable inputs as a poetry editor.

Audio: Sudhanva Deshpande is an actor and director with Jana Natya Manch, and an editor with LeftWord Books.