Anytime now, they’ll take off from a thousand runways in Ahmedabad alone. A sight more colourful and brilliant than any known air parade. Their proud pilots and owners are both ground-based. None of them aware that the craft they’re flying have been readied – each and every one of them – by ground crews of up to eight who work almost round the year to keep the industry airborne. Crews mostly women, often rural or small town-based, and who earn a pittance for their complex, delicate but arduous work, and who will never be high-fliers themselves.

It’s Makar Sankranti time, and the kaleidoscopic colours of many of the kites to be flown in the city in celebration of this Hindu festival were made in Ahmedabad itself and in Khambhat

taluka

of Gujarat’s Anand district – by women from Muslim and poor Hindu Chunara communities. The majority of fliers, naturally, will be Hindus.

These women work for more than 10 months a year making kites – for very meagre returns – especially those colourful ones that decorate the sky on January 14. Women account for 7 of every 10 of the 1.28 lakh people finding work in this

Rs. 625 crore industry

in Gujarat.

“A

patang

[kite] has to pass through seven pairs of hands before it’s ready,” says 40-year-old Sabin Abbas Niyaz Hussein Malik. We’re seated inside his 12 x 10 foot home-cum-shop in a small lane of Khambhat’s Lal Mahal area. And he’s enlightening us on the less known side of this outwardly beautiful industry, seated against the glossy silver backdrop of packages with kites wrapped and ready to be sent off to the sellers.

Left: Sabin Abbas Niyaz Hussein Malik, at his home-cum-shop in Khambhat’s Lal Mahal area. Right: A lone boy flying a lone kite in the town's Akbarpur locality

Colourful kites decorate the sky on Uttarayan day in Gujarat. Illustration by Anushree Ramanathan and Rahul Ramanathan

Colourful unpacked kites strewn all around cover more than half the floor of his one-room home. He is a third-generation contract manufacturer, working through the year with an army of 70 craftspeople to get supplies ready for Makar Sankranti . You could say he’s the eighth pair of hands handling those kites.

For believers, Makar Sankranti signifies the movement of the sun into the zodiac symbol of

makar

(Capricorn). It is also a harvest festival celebrated across India with different traditions and names, like Magh Bihu in Assam, Poush Parbon in Bengal and Pongal in Tamil Nadu. In Gujarat it is called Uttarayan, which signals the northward journey of the sun during the winter solstice. Uttarayan is today synonymous with the kite-flying festival.

Growing up in the old city of Ahmedabad one always took patangs for granted. They were little paper birds in many sizes and shapes that flew out from old trunks hidden in attics or were bought from crowded old city markets days before they filled the sky on Uttarayan. No thought was spared for the history of the kite or the craft of making it, let alone the lives of its makers – that invisible ground crew working around the year to keep our patang s in flight for a brief while.

The flying of kites is this season’s obsessive sport for children at play. The making of kites is anything but child’s play.

*****

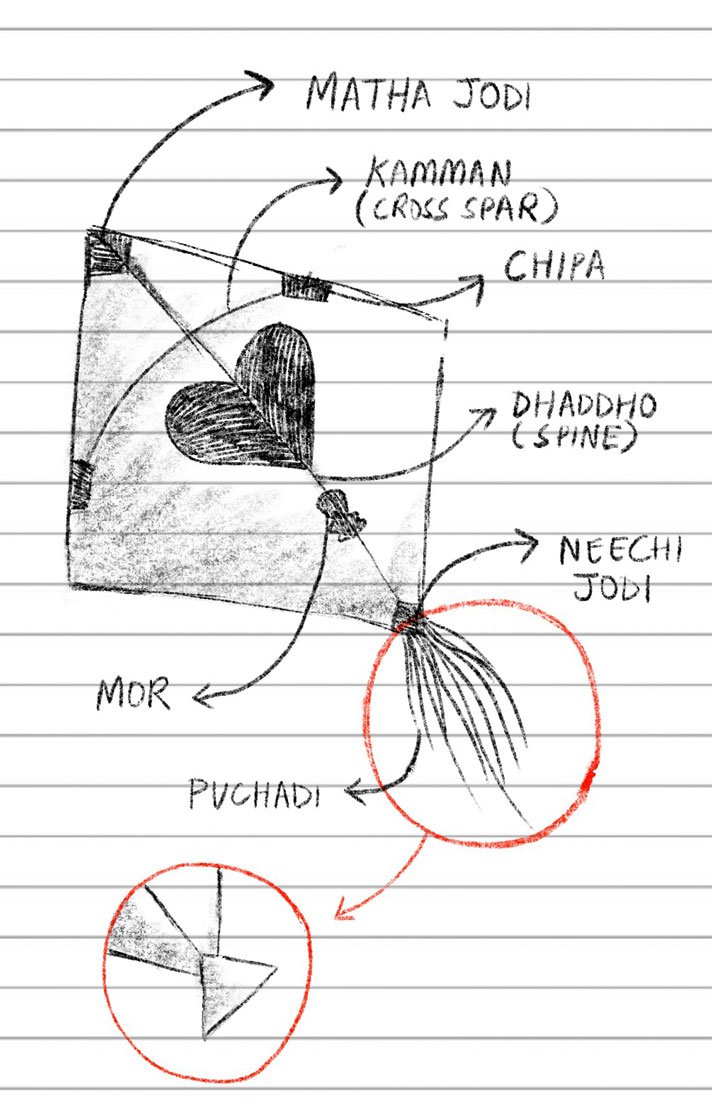

Left: Sketch of the parts of a kite. Centre: In Ahmedabad, Shahabia makes the borders by sticking a

dori

. Right:

Chipa

and

mor

being fixed on a kite in Khambhat

“Each task is done by a different karigar [craftsperson],” Sabin Malik explains. “One person cuts the paper, another pastes the paan [a heart shaped cut-out], a third one does dori [a string border affixed to the kite], and a fourth attaches the dhaddho [spine]. Next, another karigar fixes the kamman [cross spar], yet another sticks the mor , chipa , matha jodi , neechi jodi [reinforcements glued onto different parts], and one makes a phudadi [tail] that will be attached to the kite.”

Malik holds a kite in front of me and explains, pointing at each part with his finger. I make a sketch in my notebook to understand. The work on this simple contraption actually happens across multiple localities in Khambhat.

“In Shakarpur, about a kilometre away, we get only one task done, the

dori

border,” says Sabin Malik, explaining his network. “In Akbarpur they only do

paan

/

sandha

[design joints]. In nearby Dadiba they stick

dhaddha

[spines]. In Nagara village, three kilometres away, they stick

kamman

, in Mutton Market they do

patti kaam

[adding of reinforcement tapes]. They also make

phudadis

there.”

This is also the story of everyone in kite manufacturing in Khambhat, Ahmedabad, Nadiad, Surat and elsewhere in Gujarat.

Left: Munawar Khan at his workshop in Ahmedabad's Jamalpur area. Right: Raj Patangwala in Khambhat cuts the papers into shapes, to affix them to the kites

Munawar Khan, 60, is from the fourth generation in the same business in Ahmedabad. His work begins by sourcing the kite papers, Bellarpur or Tribeni, both named after the manufacturers – Bellarpur Industries in Ahmedabad and Tribeni Tissues in Kolkata. Bamboo sticks are ordered from Assam and are cut into varied sizes in Kolkata. The paper reams he buys go to his workshop to get cut into assorted sizes and shapes.

Placing them in neat bundles of about 20 sheets each, he starts slitting the pile into the required sizes for kite papers, using a broad knife. He then stacks and delivers them to the next

karigar

.

In Khambhat, Raj Patangwala, 41, does the same work. “I know all the tasks,” he says, cutting free-flowing shapes for his kites as he speaks. “But I cannot handle too many on my own. We have many workers in Khambhat, some work on big kites, some on small ones. And for each of the sizes you have 50 varieties of kites.”

Different coloured kites of many shapes would be fighting spectacular battles in the sky by the time my inexpert hands could get the ghenshiyo (a kite with a tassel at the bottom) to cover a short distance of about three metres from our terrace. The sky would be studded with cheels (bird-shaped fighter kites with longer wingspan), chandedars (a kite with tangent circles), pattedars (with diagonal or horizontal stripes in more than one colour), and many more types.

Left: In Khambhat, Kausar Banu Saleembhai gets ready to paste the cut-outs. Right: Kausar, Farheen, Mehzabi and Manhinoor (from left to right), all do this work

The more complex the design, colour and shape of a kite, the more work by skilled labour it requires to fix together its many pieces. Kausar Banu Saleembhai, in her 40s, and living in Khambhat’s Akbarpur locality, has been doing this work for the last 30 years.

She mixes and matches the colourful shapes to kite covers and glues them together at their edges to complete a design. “We are all women doing this work here,” Kausar Banu says, pointing at those gathered. “Men do other things, like cutting the paper in the factories or selling the kites.”

Kausar Banu works in the morning, afternoon, and often at night. “Most of the time I get 150 rupees for a thousand kites that I make. In October and November, when the demand is at its peak, that could be 250 rupees,” she explains. “We women work in the house and cook as well.”

A 2013

study

by the Self Employed Women’s Association confirmed that 23 per cent of women in the industry were earning less than Rs. 400 a month. A majority of them made between Rs. 400 and Rs. 800. A mere 4 per cent earned above Rs.1,200 a month.

It means the majority of them earn less in a month than the sale of a single large, designer kite that can fetch at Rs. 1,000. If you buy the cheapest kite, you have to pick up a pack of five for around Rs. 150. The high-end ones can cost Rs. 1,000 or more. In between, the range of prices is as bewildering as the number of varieties, shapes and sizes. The smallest kites here are 21.5 x 25 inches. The largest can be two to three times that size.

*****

Left: Aashaben, in Khambhat's Chunarvad area, peels and shapes the bamboo sticks. Right: Jayaben glues the

dhaddho

(spine) to a kite

As my kite returned to the terrace after traversing a minimal distance, I remember an onlooker shouting “ dhaddho machad! ” (“twist the central bamboo spine”). So I held the kite from the top and bottom end with my small hands, and twisted its spine. The spine needs to be supple but not so weak as to snap upon twisting.

Decades later, I’m watching Jayaben, 25, in Chunarvad in Khambhat, as she glues that supple central bamboo spine to the kite. The glue that she uses is homemade, prepared with boiled sabudana (sago). An artist like her gets Rs. 65 for sticking a thousand spines. The next worker in the production chain line needs to fix the kamman (cross spar) to the kite.

But wait, the

kamman

needs to be polished and smoothened. Ashaben, 36, of Chunarvad has been peeling and shaping those bamboo sticks for years. Sitting in her house with a bundle of sticks, a piece of bicycle-tube rubber wrapped around her index finger, she peels them with a sharp razor knife. “I get some 60 to 65 rupees for peeling a thousand such sticks,” Ashaben says. “Our fingers get so coarse doing this work. You can even bleed when you work with the bigger ones.”

Now the kamman is smooth, and it has to go through a banding process. Jameel Ahmed, 60, has a small shop in Ahmedabad’s Jamalpur area and still does some form of banding for the kammans . He runs a bunch of bamboo sticks on his multi-burner kerosene lamp box lit with eight flames. The process makes black band marks appear on bamboo sticks.

Left: At his shop in Ahmedabad's Jamalpur area, Jameel Ahmed fixes the

kamman

(cross par) onto kites. Right: He runs the bamboo sticks over his kerosene lamp first

Left: Shahabia seals the edge after attaching the string. Right: Firdos Banu (in orange salwar kameez), her daughters Mahera (left) and Dilshad making the kite tails

Jameel uses a special glue to fix his kammans . “In making a kite you need three to four types of glues, each with different ingredients and consistency.” He is using a light blue one, made from maida mixed with cobalt pigments known as mor thu thu . The rate for fixing kammans is Rs. 100 for every thousand.

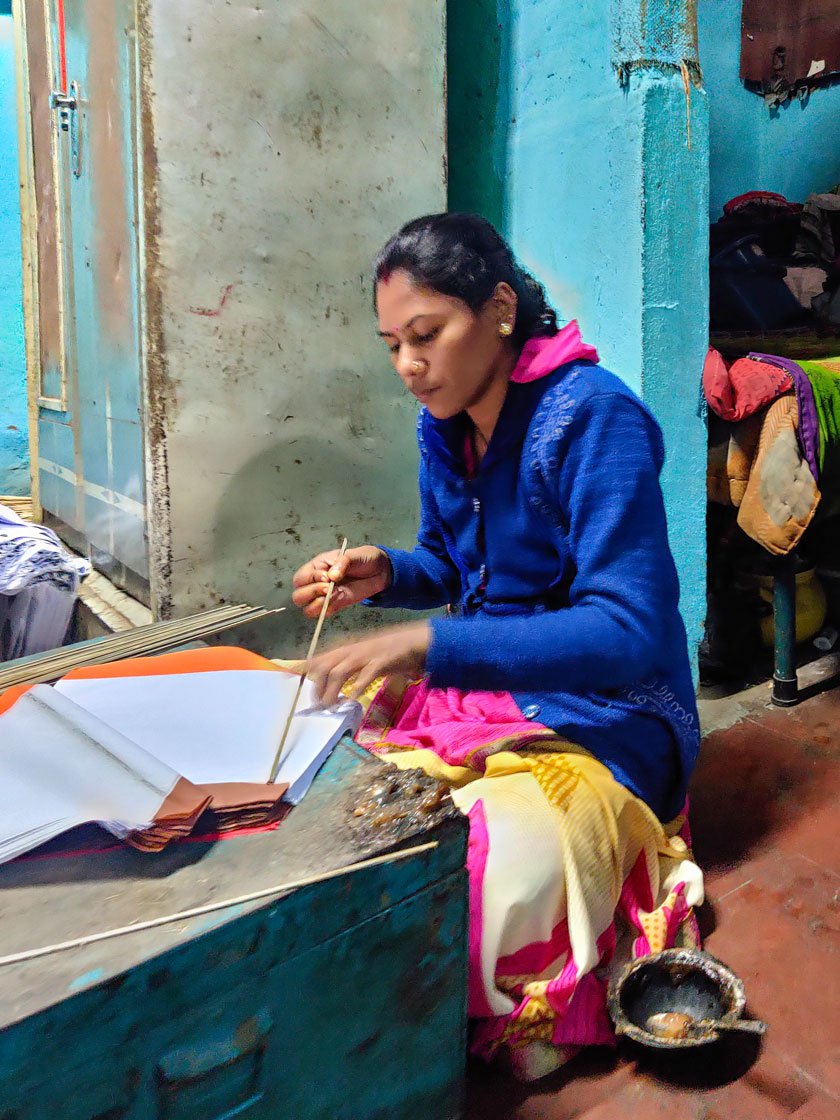

The glue that 35-year-old Shahabia, in Juhapura, Ahmedabad, uses for the

dori

border work is different from Jameel’s. She makes it from cooked rice at home. She’s been doing it for ages, she says, as she pulls a very fine strand from the thick bunch of thread hanging over her head from the ceiling. She swiftly runs the string around the kite’s perimeter, transferring the thin film of glue sticking to her fingers onto the thread. A bowl full of

lai

(rice glue) lies hidden under her low desk.

“I cannot do this work once my husband comes home. He gets angry if I am doing all this.” Her work gives strength to the kite and stops it from fraying. She gets anything between Rs. 200 to Rs. 300 for every thousand kite borders she makes. Thereafter, other women fix small bits of paper to each kite to reinforce its spine and hold the edge of the cross spar in place. They earn Rs. 85 for every thousand kites they finish.

Firdos Banu, 42, lets rolled-up rainbows hang from her hand in front of us – bright and colourful kite paper-tassels (or tails) strung together, 100 in a bunch. Wife of an auto driver in Akbarpur, she used to make

papad

on order earlier. “But that was too tough, given that we do not have a terrace of our own to dry the

papads

. This isn’t an easy job either and pays me poorly,” says Firdos Banu, “but I don’t know anything better.”

The more complex the design, colour and shape of a kite, the more work by skilled labour it requires to fix together its many pieces

With long sharp scissors, she cuts the paper from one side into strips, depending on the size of the tassels she is making. She then hands over the cut paper to her daughters Dilshad Banu, 17, and Mahera Banu, 19. They take one cut-paper at a time and apply a little of the pre-made lai to the centre of the paper. Each pulls a thread from a bunch she’s wrapped around her toe, and with a thin loop, wraps the paper, twisting it around into a perfect phudadi . When the next karigar in the chain ties the tail to the kite it will be flightworthy. And when the three women together have made a thousand of these tails, they will earn all of Rs. 70 between them.

“ Lappet … ! ” [“reel in your string”] – the cries were aggressive this time. The manjha from the sky fell, heavy and limp, across terraces. Yes, decades later, I still remember losing that kite I loved.

I don’t fly kites anymore. But this week has been about meeting those who still make it possible for successive generations of children to fly high. Those whose unending labour gives us the colours of Makar Sankranti.

The author would like to thank Hozefa Ujjaini, Sameena Malik and Janisar Sheikh for their help in reporting the story.

Cover photo: Khamroom Nisa Banu works on plastic kites, which are popular now. Photo by Pratishtha Pandya.

This story is part of a series of 25 articles on livelihoods under lockdown, supported by the Business and Community Foundation.