“When women like us leave their homes and farms and come to the city to protest, it means they are losing the maati [ground] beneath their feet,” said Aruna Manna. “In the last few months there were days when we hardly had anything to eat. On other days we survived on barely one meal. Is this the time to pass these laws? As if this mahamari [the Covid-19 pandemic] was not enough to kill us!”

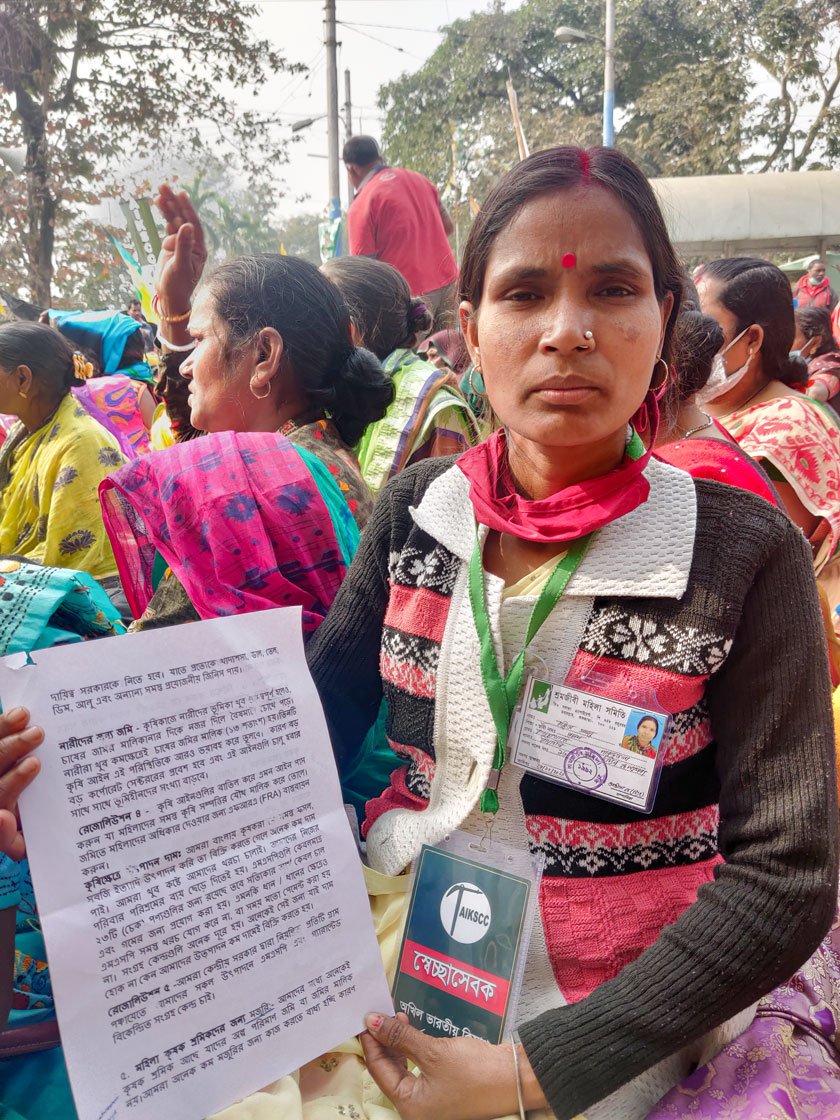

Aruna, 42, was speaking at the Esplanade Y- Channel – a protest site in central Kolkata, where, from January 9 to 22, farmers and farm labourers have come together under the banner of All India Kisan Sangharsh Coordination Committee (AIKSCC). Students, citizens, workers, cultural organisations all gathered here too – all in solidarity with the farmers protesting at the borders of Delhi against the three farm laws passed in Parliament in September 2020.

Aruna had come here from Rajuakhaki village, along with roughly 1,500 other women, most of them from various villages of South 24 Parganas district. They arrived in Kolkata on January 18 by trains, buses and tempos to mark the nationwide Mahila Kisan Diwas – a day dedicated to women in farming, and to ensuring their rights. More than 40 unions of women farmers and farm workers, women’s organisations, and the AIKSCC organised the West Bengal edition of the event.

Though tired after the long journey to Kolkata to make their voices heard, the women’s rage was still evident. “So who will protest for us? The courtbabus [judges]? Till we don’t get our dues we will protest!” said Suparna Haldar, 38, a member of the Shramajeevi Mahila Samiti, reacting to the recent comment made by the Chief Justice of India that women and elderly protestors should be ‘persuaded’ to leave the protests against the farm laws.

Suparna was speaking at the Mahila Kisan Majur Vidhan Sabha session, held on January 18 at the Kolkata protest site from around 11:30 a.m. to 4 p.m. as part of Mahila Kisan Diwas The session focussed on the complex concerns of women in farming, their labour, their long struggle for ownership of land and other rights, and the potential impact of the new farm laws on their lives.

On January 18, women from several districts of West Bengal attended the Mahila Kisan Majur Vidhan Sabha session in Kolkata

Suparna, who had come from Pakurtala village in Raidighi gram panchayat of South 24 Parganas district , spoke of how rising input costs and recurring cyclones have made subsistence farming unsustainable in her area. As a result, work at MGNREGA sites (locally known as eksho diner kaaj or 100 days’ work) and at other government-funded and panchayat -run worksites has become a crucial lifeline for agricultural labourers and farm families with very small land holdings.

While the Kolkata protest meeting focussed on the repeal of the three farm laws, the scarcity of MGNREGA work days and of work under the local panchayats was also a recurring concern among the women present.

“Work is not available All of us have valid job cards [though job cards are usually issued in the names of husbands or fathers, and this too is a contentious issue for many of the women]. Yet we don’t get work,” said Suchitra Haldar, 55, who looks after the allotment of 100 days’ work in Balarampur village in Raidighi panchayat , which is located in Mathurapur II block. “We have been protesting against this for long. If we manage to get work, we don’t get our payment on time. Sometimes we don’t get it at all.”

“The young generation in our village is sitting idle, no work for them,” added Ranjita Samanta, 40, of Rajuakhaki village. “Many men have returned during the lockdown from the places where they went to work. Parents are out of jobs for months, and so the new generation is also suffering. How are we supposed to live if we don’t even get 100 day’s work?”

Sitting at some distance was 80-year-old Durga Naiya, wiping her thick glasses with the edge of her white cotton saree. She had come with a group of elderly women from Gilarchhat village of Mathurapur II block. “I used to work as a khet-majur [agricultural labourer], till I had strength in my body,” she said. “See, I have become so old now… my husband died long time ago. I am unable to work now. I have come here to tell the sarkar to give old farmers and khet-majurs their pension.”

Durga Naiya is a veteran of farmers’ protests. “I went to Delhi with her in 2018 to join other farmers from the country,” said Parul Halder, a landless labourer in her 50s from Radhakantapur village in Mathurapur II block. They had walked together from New Delhi railway station to Ramlila Maidan in November 2018 for the Kisan Mukti Morcha .

Ranjita Samanta (left) presented the resolutions passed at the session, covering land rights, PDS, MSP and other concerns of women farmers such as (from left to right) Durga Naiya, Malati Das, Pingala Putkai (in green) and Urmila Naiya

“We are barely surviving,” said Parul, when asked why she had joined the elderly women at the protest site. “There is not much work available in the farms. During the harvest and sowing seasons, we get some work and earn up to Rs. 270 a day. But that doesn’t sustain us. I roll beedis and do other odd jobs. We have seen very bad times during the mahamari and especially after Amphan… [the cyclone that hit West Bengal on May 20, 2020]”

The elderly women in this group were very careful about their masks, aware of their vulnerability during the pandemic – still, they decided to participate in the protest. “We got up very early. It’s not easy to reach Kolkata from our villages in the Sundarbans,” said 75-year-old Pingala Putkai from Gilarchhat village. “Our samiti [the Shramajeevi Mahila Samiti] arranged a bus for us. We got packed lunch here [with rice, potato, laddoo , and a mango drink]. It is a special day for us.”

In the same group was Malati Das, 65, who said she is waiting for her widow’s pension of Rs. 1,000 a month – she has not received it even once. “The judge says the elderly and women should not participate in protest,” she added. Jeno buro aar meyenamushder pet bhore roj polau ar mangsho dichhe khete [As if they are feeding the old and womenfolk with pulao and meat curry]!”

Many of the women in this group, who have retired from farm work, echoed a long-standing demand for a dignified pension for elderly farmers and farm workers.

While most of the women at the meeting from the Sundarbans who I spoke to belonged to various Scheduled Castes, there were also many from Adivasi communities. Among them was Manju Singh, 46, a landless agricultural labourer from the Bhumij community, who had come from Mohanpur village in Jamalpur block.

“Let the bicharpati [judge] send us everything at home – food, medicines and phones for our children,” she said. “We will stay at home. No one likes the kind of harbhanga khatuni [back breaking hard labour] that we do. So what do we do if not protest?”

'The companies only understand profit', said Manju Singh (left), with Sufia Khatun (middle) and children from Bhangar block

In her village in Purba Bardhaman district, she added, “Under the 100 days’ work scheme, we barely manage to get 25 days of work [in a year]. The per day wage is Rs. 204. What is the use of our job card if it doesn’t ensure work? Eksho diner kaaj shudhu naam-ka-waste [It is called 100 days’ work for nothing]! I mostly work on private farmlands. We were able to ensure a daily wage [from landowners] of Rs. 180 and two kilos of rice in our area after a long struggle.”

Arati Soren, a Santal Adivasi landless farmworker in her mid-30s, had also come from the same village, Mohanpur. “Not just about the wages, our struggles are manifold,” she said. “Unlike others, we have to fight for each and every thing. Only when women from our community come together and shout in front of the BDO office and panchayats they listen. These laws will make us starve. Why don’t the bicharpatis ] take the laws back instead of telling us to go back home?”

For the last 10 months, Arati’s and Manju’s husbands have been at home, after they lost their jobs at small private firms around Kolkata. Their children could not afford smartphones for online schooling. A severe shortage of work under MGNREGA added to their problems. The lockdown that came with the pandemic forced many of the women agricultural labourers to survive on loans taken from mahajans (moneylenders). “We have survived on the rice the government allocated,” said Manju. “But is only rice good enough for the poor?”

“Women in the villages suffer from anaemia,” said Namita Halder, 40, from Raidighi village of Raidighi gram panchayat in, South 24 Parganas, and a member of the Paschim Banga Khetmajur Samiti. “What we need is free treatment at good government hospitals; we cannot afford the big private nursing homes. The same thing will happen with farming if these laws are not taken back! If the sarkar opens everything for the big private companies, then the poor won’t get the little food that they manage now somehow. The companies only understand profit. They don’t care if we die. We won’t be able to buy the food that we grow.”

For her too, there is no question of women not being at the protest sites. “Women have been in farming from the very inception of civilisation,” she said.

Namita Halder (left) believes that the three laws will very severely impact women farmers, tenant farmers and farm labourers

Namita believes that the three laws will impact women like her very severely – women tenant farmers and farm labourers who take land on lease and cultivate paddy, vegetables and other crops. “If we don’t get the right price for our produce, how will we give food to little children and aged in-laws and parents?” she asked. “The big company maaliks will hoard and control the price by buying the crops from us at a very low price.”

The laws the farmers are protesting against are the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020 ; the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act , 2020; and the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020 . The laws have also been criticised as affecting every Indian as they disable the right to legal recourse of all citizens, undermining Article 32 of the Constitution of India.

The various demands of the women farmers and farm workers were reflected in the resolutions passed by this Vidhan Sabha. These include an immediate repeal of the three farm laws; recognition of women’s labour in agriculture by giving them the status of farmers; a law to guarantee minimum support prices (MSP) according to the recommendation of National Commission on Farmers (Swaminathan Commission); and strengthening the PDS (public distribution system) for rations.

At the end of the day, a long mashal michhil (torch rally) of around 500 women, with women farmers from Muslim households in Bhangar block of South 24 Parganas lit up the evening against a darkening sky.

llustration: Labani Jangi, originally from a small town of West Bengal's Nadia district, is working towards a PhD degree on Bengali labour migration at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata. She is a self-taught painter and loves to travel.