“ Kudalu! Kudalu! Patre Kudalu [Hair! Hair! Vessels for hair!]”

Sake Saraswathi’s high-pitched voice fills the streets of Mathikere in Bangalore as she goes from house to house collecting human hair. In exchange, she offers lightweight aluminium kitchen utensils – small water containers, pots and pans, cooking spoons, large sieves and more.

“I learnt this work from my sister-in-law, Shivamma. She [also] taught me how to throw my voice to get more customers,” the 23-year-old vendor in Bangalore says.

The third generation in her family to do this work, Saraswathi says, “My mother, Gangamma, has been doing this work since before her marriage, but she reduced her work as she has severe back and knee problems." Her father, Pullanna and mother, Gangamma migrated from Andhra Pradesh to Bangalore 30 years ago.

The family belongs to the Koracha community who are listed as Other Backward Class (OBCs) in Andhra Pradesh. Now the 80-year-old Pullana makes jhadus (brooms) from dried date palm leaves and sells each for Rs. 20-50.

Saraswathi lives with her family in Kondappa layout in north Bangalore. She has been collecting hair from households since she was 18

Her father's earnings were not enough and so five years ago when Saraswathi turned 18, she started working while completing her BCom degree. The family live in Kondappa layout in north Bangalore – her parents, two older brothers, their wives and children.

Saraswathi attends college from Monday to Saturday. On Sundays, her day starts at 6 a.m., when she begins collecting hair from various homes. She cooks breakfast for her family before leaving. “The children get hungry when we are out , so I cook some extra,” she says.

Saraswathi and her sister-in-law, Shivamma leave for work with the tools they will need: a greyish shoulder bag carrying the aluminium vessels and steel container, similar to that of a milkman’s vessel, which they use to collect hair.

“We make sure to treat ourselves before we start work,” says Saraswathi. They usually get a plate of idli vada , an omelette or masala rice.

Some areas they try to visit every week are Mathikere, Yelahanka New Town, Kalyan Nagar, Banaswadi and Vijaynagar. Saraswathi’s routes pass through low to middle-income localities.

Saraswathi offers households lightweight aluminium vessels — small water containers, pots, pans, cooking spoons and more for in exchange for the hair collected. She then sells the hair to dealers for making wigs

The duo usually work for 10 hours and take two breaks in that time, so they can eat.

The households that Saraswathi visits collect hair in plastic bags, plastic food containers, plastic jars, tin boxes and even torn milk packets.

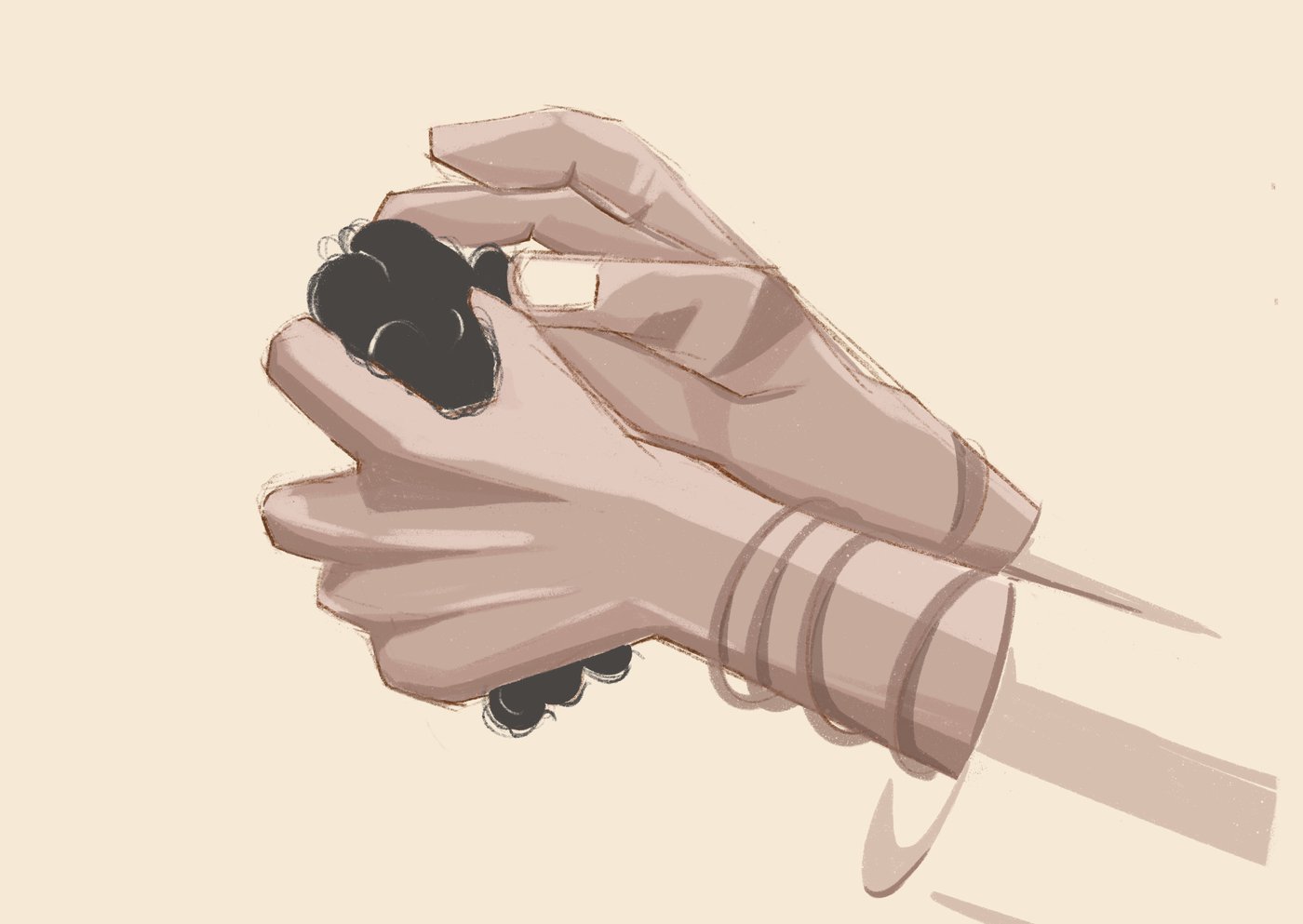

“I check the hair [quality] by stretching it,” says Saraswathi, adding, “Beauty parlours have hair that is cut, and that does not work.” The trick is to get 'remy hair' which is “hair from the roots with the cuticle still intact.” There is even a minimum length criterion, which is more than six inches.

Without a proper measuring tool, they must rely on wrapping the hair at least twice around their fist to check the length; then they twirl it into a ball.

After measuring the hair, Saraswathi or her sister-in-law pull out the lightweight aluminium vessels and offer two options to the person from whom they are buying hair. “If the customers are picky, they will argue with us and fight to get a bigger vessel for a very small quantity of hair,” she explains.

The hair Saraswathi collects needs to be six inches or more in length. With no measuring tool, she wraps the hair at least twice around her fist to check the length

Happy with the length, she then twirls the strands into a ball

Since all households use vessels, they are a good currency for exchange. But she says some customers still insist on money. “But we cannot give them money. For just 10 to 20 grams of hair they ask for more than 100 rupees!”

In a day, she only gets a handful of hair, sometimes even less than 300 grams. “There have been times when I go to homes asking for hair and I get replies — 'hair is over',” she says. “You never know which area they [others collecting hair] have already covered.”

Saraswathi sells the collected hair to Parvati amma , a dealer.

“Hair rates are seasonal. This guarantees no fixed income for the family. Generally, one kilo of black hair costs anything between 5,000 to 6,000 rupees. But during the rainy season, the rates drop to 3,000 or 4,000 rupees per kg.”

Parvati amma weighs the hair on a digital weighing machine.

Left: Saraswathi buys aluminium vessels from different wholesale markets in Bangalore. Parvati amma weighs hair on her weighing machine

Companies buy the hair from Parvati amma and make wigs out of them. “About 5,000 women work to separate and clean the hair,” the 50-year-old Parvati says. “They use soap, oil, shampoo and leave it overnight till it’s clean and dry. The men then check the length of the hair before it is sold.”

Saraswathi plans ahead. “If I want to buy the vessels today, I need to collect money for yesterday’s hair from Parvati amma ,” she explains. “I do not wait a month to sell the hair. As soon as I receive it, I sell it.”

The hair collector says that she covers a distance of 12 to 15 kilometres on foot because, “The bus conductors don’t let us get on the KSRTC [state] buses.”

“This work takes a toll on my body. I get pain in my body and neck,” as the constant shifting of weight from one shoulder to the other. But she continues with it.

“This trade barely fills our pockets,” she adds.