And so the People’s Archive of Rural India turns seven today, December 20. We didn’t just survive the pandemic and its lockdowns – we produced our best work ever.

On the very first day of the lockdown last year, the government of India declared the media, both print and electronic, an essential service. That was good. Never had the Indian public needed journalism and journalists more. There were stories to be told on which people’s lives and livelihoods depended. How did the big media houses of this country respond? By sacking 2,000 to 2,500 journalists and over 10,000 non-journalist media workers.

So how were they going to tell the big stories? By getting rid of some of their best reporters? Thousands of other mediapersons – those not retrenched – had their salaries slashed by anywhere between 40 and 60 per cent. Travel by journalists was strictly curbed, not as a precaution to preserve their health, but to cut costs. And such stories as were done, especially after the first two weeks from March 25, 2020, were largely city or big-town bound.

PARI added 11 people to its staff since April 2020, did not impose a single paisa’s pay cut on anyone – and in August 2020, handed out promotions and increments to almost all our staffers.

Apart from our other reporting which remained prolific, PARI – from when the pandemic began – published over 270 (mostly multimedia) stories and important documents and reports, on the single theme of livelihoods under lockdown. These stories we brought in from 23 states, from almost every major region of the country, from the villages including those the migrants were returning to, with reporters travelling hundreds of kilometres on whatever transport they could manage during the lockdowns. You’ll find over 65 different reporters’ bylines on these stories. PARI was covering migrant workers for years before the pandemic and did not have to discover them on March 25, 2020.

As our readers know, and for others who don’t, PARI is both a journalism platform and a living, breathing archive. We are the largest online repository of articles, reports, folk music, songs, photographs, and films on rural India and one of the biggest repositories of the rural anywhere. PARI’s journalism is based on reporting the everyday lives of everyday people. And on telling the stories of 833 million rural Indians through their voices and lived experience.

We at PARI have produced some of our best work during the pandemic-lockdowns, including an ongoing award-winning series on women's reproductive health (left) and detailed coverage of the farmer's protests (right) against the now-repealed farm laws

In these first 84 months of our existence, PARI has won 42 awards – one every 59 days on average. Of these, 12 are international awards. And a total of 16 were won for stories done during the lockdown periods. In April 2020, the United States Library of Congress informed us that they had selected PARI for inclusion in their web archives, saying: "We consider your website to be an important part of this collection and the historical record."

PARI also published an award-winning series on Women’s Reproductive Health from 12 states of the country, particularly from those states where women’s rights in this sector are the most fragile. Of 37 stories in this ongoing series, 33 were done and published after the outbreak of the pandemic and during the lockdowns. The series represents the first nationwide journalistic survey on women’s reproductive health rights with the stories told through the voices of rural women themselves.

Our work during the most difficult times saw our readership grow by close to 150 per cent and our social media platforms like Instagram grow by nearly 200 per cent. Importantly, readers of PARI on Instagram sent millions of rupees to the people in the stories we did – directly.

Alongside all this, we also published 65 detailed stories by 25 reporters and photographers, and 10 vital documents, on the farmers’ protests against the now-repealed farm laws. Stories of a kind you are unlikely to find in the ‘mainstream' media. These were not just from the gates of Delhi, but from several other regions across half a dozen states.

Our stories looked at who the individual farmers in this historic movement were, where they came from, what the state of their agriculture was, what they were demanding, what provoked them so strongly as to come and camp at Delhi, missing out on being with their families for a year or more. Foregrounding voices not of lobbyists or elite think tanks – but of everyday farmers. It was PARI that first reported this as the largest, peaceful, democratic protest the world has seen in years. That too, one built in the midst of a pandemic.

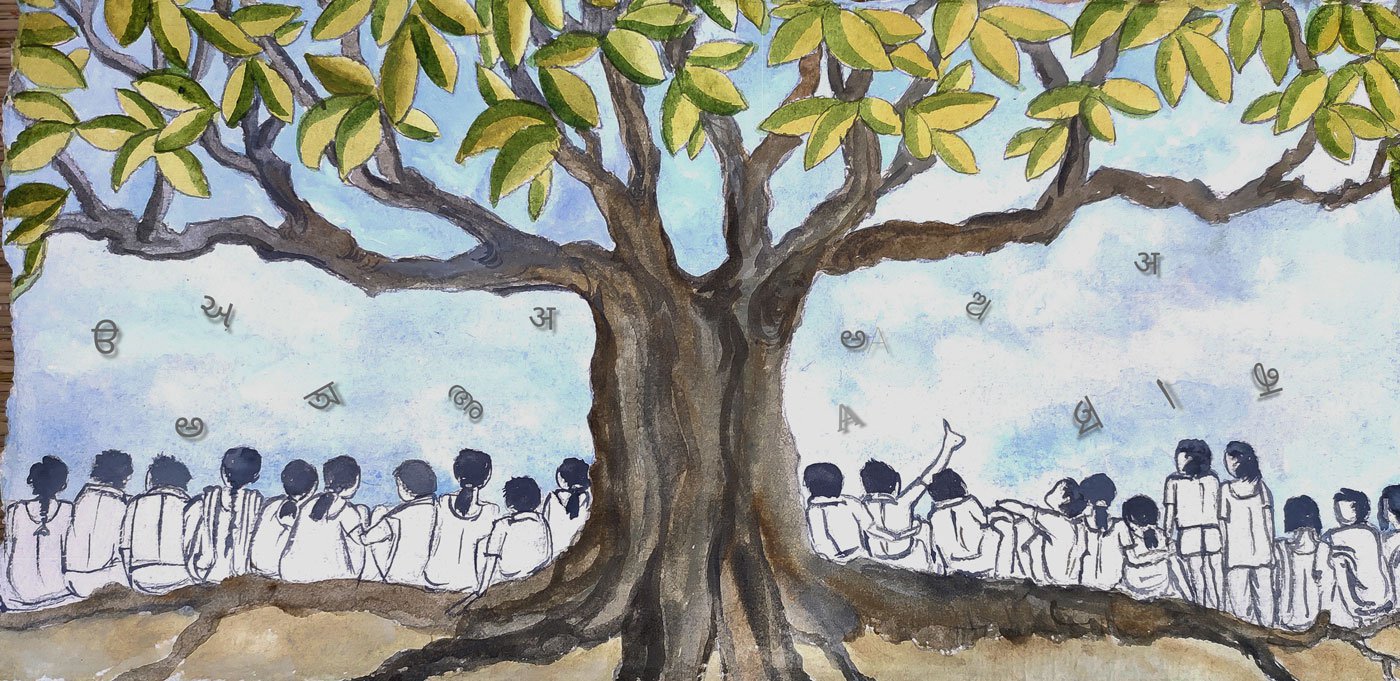

With PARI's extensive translations, readers, including students from diverse backgrounds, can read our stories in multiple languages (left). In one year of existence, PARI Education has published 135 articles (right) by students from 63 locations

Launched in just English in December 2014, PARI now publishes in 13 languages almost simultaneously – and will add more. We believe in parity, that is, any story coming to us in one language has to be published in all 13. We believe Indian languages are at the soul of rural India and that Every Indian language is your language . And we now run the largest translations programme for any journalism website anywhere. Our translators include doctors, physicists, linguists, poets, homemakers, teachers, artists, journalists, writers, engineers, students, and professors. The oldest is 84 and the youngest, 22. Some are based outside of India. Others live in remote locations within the country, with very poor connectivity.

PARI is free to access. There is no subscription fee. No articles tucked away behind paywalls. And we carry no advertising at all. There’s already too many media outlets drowning young people in ads, creating artificial needs and wants. Why add to that? Close to 60 per cent of our readers are below the age of 34 – and nearly 60 per cent of those are in the age group 18-24. As are many reporters and writers and photographers we work with.

Our youngest section, PARI Education , has in a single year of existence, moved rapidly ahead on another mandate of ours: creating the textbooks of the future. As many as 95 educational institutions and 17 organisations in the education sector are using PARI as a textbook and as a means to explore and learn about rural India. Of these, over 36 are working with us to create PARI-centred curricula that will get students to engage directly with marginalised people. PARI Education has published 135 reports by students from 63 locations – on problems in farming, vanishing livelihoods, gender issues and more. Since January 2021, this section has conducted over 120 online talks and workshops in India's top universities as well as in remote rural schools.

‘Rural’ for PARI is not an idyllic or romanticised Indian countryside, nor a glorified blend of cultural practices, nor even a nostalgic idea of living that needs to be curated and exhibited. PARI's journey is an exploration of the complexities and exclusions on which rural India is built. All of it – the beautiful and the brilliant, the brutish and the barbaric. PARI itself is an ongoing education for all of us who work in it – we respect the knowledge and skills that ordinary Indians bring to us. That is one of the reasons why we centre our storytelling around their voices and lived experience of some of the most critical issues of our time.

Our award-winning series on climate change (left) reports this subject through the voices and lived experience of everyday people, and we continue to build our unique section on India’s last living fredom fighters (right)

Our award-winning series on climate change – to be published as a book by the UNDP – reports this subject through the voices and lived experience of farmers, labourers, fishermen, forest dwellers, seaweed harvesters, nomadic pastoralists, honey collectors, insect-trappers and more. And that from fragile mountainous ecosystems, forests, seas, coastal areas, river basins, coral islands, deserts, arid and semi-arid zones.

Abstract and jargonised coverage in conventional media distances readers from the process – and builds stereotypes of climate change being only about the melting of the Antarctic sheet, or the gutting of the Amazon forests, or bushfires in Australia. Or in terms of negotiations at intergovernmental conferences, or important but unreadable IPCC reports. PARI’s reporters tell audiences stories through which they can relate to climate change as being much closer to their own lives.

As the country journeys through its 75th year of Independence, we continue to build our unique section on India’s

last living freedom fighters

, in text, video and audio. In 5-7 years, no one from that golden generation will be around, and India’s children will never get to see or hear or talk to a genuine warrior in this nation’s fight for freedom and independence. On PARI they can listen to them, see them, hear them explain in their own words what our freedom struggle was really about.

We may be a very young media platform of very limited resources – but we run the biggest fellowships programme in Indian journalism. Our aim is to have a Fellow writing out of and about every one of the 95 (natural-physical and historically evolved) regions – and from the rural areas within those. Well over half our 30 Fellows so far have been women, and several from minorities and other sections of society conventionally excluded from and by the media.

We have also had in these 7 years, 240 interns, including 80 in PARI Education, spending 2-3 months training at PARI and learning this very different kind of journalism.

PARI hosts the largest collection of songs composed and sung by poor women in any language in the world, the Grindmill Songs Project (left), and our FACES projects tries to map the facial diversity of this country (right)

We also host repositories of the most diverse cultures, languages, art forms and more. We are home to the largest collection of songs composed and sung by poor women in any language in the world. That is, the Grindmill Songs Project with 110,000 songs by women in rural Maharashtra and in a few villages in Karnataka. A dedicated team has translated over 69,000 of those songs into English so far.

Our coverage of folk arts and music, artists and artisans, creative writing and poetry, means we have built large collections of stories and videos on these from multiple regions across India. We also have perhaps the only archive of 10,000 black and white photographs of the Indian countryside shot across 2-3 decades. These are largely photos of people at work and, occasionally, at leisure.

We are very proud of our FACES project that tries to map the facial diversity of this country. These are the faces not of celebrities or netas but of everyday people. The aim is to have such faces from every single district and block of the country. So far the collection has 2,756 faces from 220 districts and 629 blocks across India. These FACES have been shot by 164 photographers including several undergraduate students. Overall, PARI has carried the work of 576 photographers these past seven years.

Our unique Library does not loan you books – it gives them to you for free. Any significant reports, documents, laws, even out-of-print books finding a home in the PARI Library, can be downloaded, printed and used free of charge – with appropriate acknowledgement. We function under Creative Commons 4.0. A no less unique part of this library is the PARI Health Archive that we began in the pandemic’s first year and which now houses 140 vital health-related reports and documents that go back decades but also include the latest in the field in electronic form.

PARI is free of both – governmental and corporate ownership or control. And we carry no advertising. While that ensures our independence, it also means that we depend on contributions and donations from you, our readers. That’s no cliché. If you don’t step up, we’re in trouble. Please donate to PARI , defend our independence – give good journalism a chance.