“On a normal day,” says A. Sivakumar, “I would ride my cycle 40-50 kilometres selling plastic items like buckets and pots. For this 33-year-old in Arasur – an Adivasi hamlet in Nagapattinam district – such a day would begin at 5 a.m. On a customised bicycle with colourful plastic goods, which he sells for a living, tied on all sides of it. On a normal day, he says, he’d make Rs. 300-400 – just enough to feed his six-member family.

These are not normal days.

Life under lockdown has ended that activity – and with it, his family’s source of income. But Sivakumar sees a ray of hope in the dark clouds of the Covid-19 crisis. “If not for Vanavil,” he says, “we would go hungry.”

Vanavil is the Tamil word for ‘rainbow’. It is also the name of a primary school in Sikkal village in Nagapattinam block of this district. With 44 people testing positive for the coronavirus till April 21, Nagapattinam is one of the Tamil Nadu’s Covid-19 hotspots.

The school serves mainly students from nomadic tribes and has been – even while closed for classes – arranging groceries for families in Arasur and other villages. As the lockdown’s impact deepens, the number of families the school is assisting has grown to 1,228 – almost 1,000 of those from extremely marginalised groups. For thousands of poor people here, this school is now the pivot of their food security.

Vanavil school's volunteers are delivering groceries to 1,228 families from extremely marginalised groups in Arasur hamlet and villages of Nagapattinam block

Vanavil began with aiding the nomadic groups it exists for. But, says Prema Revathi, 43, school director – and Vanavil’s managing trustee – others were also in trouble “and appeals for help came in even from villages in neighbouring Trichy [Tiruchirappalli] district.” The school’s education activities cover the districts of Nagapattinam and Thiruvarur.

When the lockdown was announced on March 24, the school sent back most of the children to their homes – barring 20 for whom Vanavil is home – hoping they would feel better with their families. A staff of five remained on campus. As the lockdown wore on, the office bearers of the school realised the children back home would neither remain healthy, nor return to school once the ordeal was over. So now they find themselves focused not just on students and their families but on a much larger, seriously disadvantaged community.

Vanavil’s focus in its education work was always on two Scheduled Tribes: Adiyans (also spelt Athiyans) and Narikuravars. The Adiyans are more widely known as Boom Boom Maattukkarar (BBM; ‘boom boom’ comes from the sound made by the mattukarar or cattle-handler on his urumi , a double-headed hourglass-shaped drum). That name has its origins in the fortune-telling occupation they adopted using highly decorated oxen as an aid or prop. Only very few of them still do that.

And there appear to be more of them than the 950 households in Tamil Nadu mentioned in Census 2011. Community organisations reckon there are just over 10,000 of them across several districts in the state. Most identify themselves as Athiyans, but many have no community certificates. There are at least 100 BBM families in Arasur, including Sivakumar’s – and this group is today surviving with Vanavil’s help.

The Narikuravars – originally hunter-gatherers – were for long listed as a Most Backward Community and gained recognition as a Scheduled Tribe only as late as 2016. Vanavil’s students, though, are mostly Boom Boom Maattukkarar.

Prema Revathi (left) with some of Vanavil's residents. Most of the school's students have been sent home, but a few remain on the campus (file photos)

The Vanavil Trust works with children of the BBMs to keep them off begging, by running a children’s home on their campus. “Like in many nomadic tribes,” says Revathi, “the kids are prone to chronic malnutrition due to a combination of reasons – chronic poverty, early marriages, multiple pregnancies, food habits. So we focus on their health too.”

For Class 11 student M. Aarthi, 16, the Vanavil hostel is her home. There is, she says, “no better way to put it.” But what’s a Class 11 student doing at a primary school? Though teaching at Vanavil – using an alternative pedagogy – is only till Class 5, it functions as a residential school as well. And accommodates students of the nomadic communities who study in government high schools. Aarthi studied in Vanavil till Class 5. She now goes to a government school – but returns to her ‘home’ here, every evening.

The school is barely 15 years old, and has already had a positive impact on Aarthi’s community. Where earlier most children saw their studies end with Class 5, four of those who finished the primary level here have studied further, have graduated, and are working. Another three are in different colleges in Chennai.

“I would have ended up like many other women in my community,” says P. Sudha, an engineering graduate currently working in a Chennai IT company. “But Vanavil changed my life.” Sudha is one of four Vanavil alumni who are the first-ever women graduates from her community. “The individual attention I got here helped me achieve the impossible.”

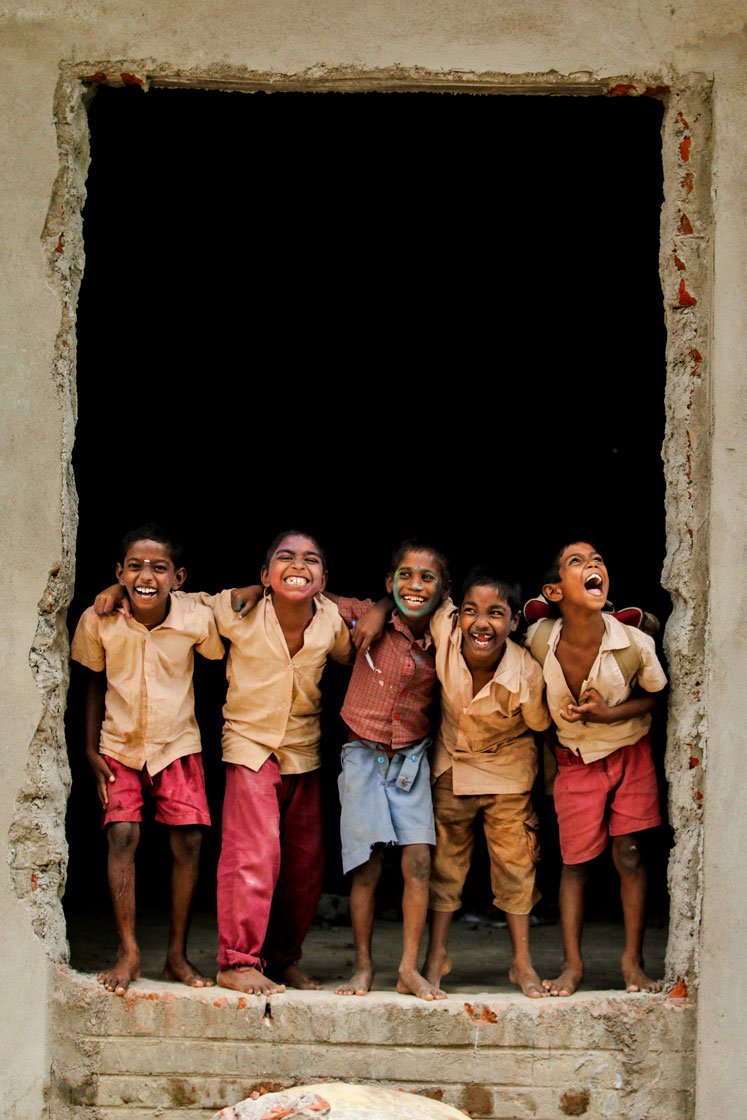

Left: A Vanavil student prepares for a play. Right: Most of them are from the Boom Boom Maattukkarar community: 'The worst affected are children because they have lost their mid-day meals' (file photos)

Pre-lockdown, 81 children – including 45 residents – were studying here. And 102 attending government schools were staying in the premises. The Trust had also set up ‘after-school centres’ at villages covering to over 500 other children who would receive a nutritious snack each evening. But now the centres are mainly stocking hand sanitisers – since the groceries are being directly delivered to a growing number of families in distress.

“In many villages,” says Revathi, “people are having only one meal a day. The worst affected are children because they have lost their mid-day meals. In Vanavil, it was not possible to give them meals here – most had gone home.” And so they started an emergency programme, perhaps too complex for a single school to handle. It extended rapidly and now many more people on the edge are receiving groceries.

To cope, Vanavil has launched a fundraiser to meet the needs of those 1,288 mainly nomadic families in nine villages of Nagapattinam and Thiruvarur and one in Thanjavur district. Now, it is reaching out to a few families in Trichy district as well. They are also trying to provide food for 20 trans-persons in Nagapattinam and 231 conservancy workers in that municipality.

The origins of the Boom Boom Maattukkarar as oxen-accompanied fortune tellers is obscured by myth. K. Raju, general secretary of the Tamil Nadu Athiyan Tribal People’s Welfare Association says: “It is believed our ancestors worked as bonded labourers of feudal landlords centuries ago. During a famine, the landlords discarded their dependents, giving them cows and bulls to get rid of them.” Others, though, say the BBMs were never an agrarian people.

“We have largely moved to selling plasticware, or dolls to ward off evil, or other menial jobs, but now we are focussing on education,” says Raju, who appreciates Vanavil’s contribution to his community on that front.

More than half of the primary school's students stay on the campus; it is also 'home' to 102 children attending government schools around Sikkal village (file photos)

Simply getting community certificates “continues to be a long-drawn struggle for our people,” says Raju. “In several villages,” explains Prema Revathi, what certificates they get “depends on the whims of the revenue divisional officer.”

Vanavil was set up just a year after the 2004 tsunami, amidst visible discrimination against nomadic peoples in many relief efforts. With such origins, it continued to intervene in calamity relief efforts, like those after the Chennai floods of 2015 and the Gaja cyclone of 2018.

Back in Nagapattinam, K. Antony, 25, is a rare, educated person in Apparakudi hamlet, who holds an engineering diploma and works in the telecom sector. The whole hamlet would have starved, he believes, but for Vanavil. “We have some musicians who play nadaswaram and thavil (a percussion instrument). But even they were only daily wagers. So it's really hard for us in times like this.” The school, says Anthony, gives him confidence.

So does young Aarthi, who says: “I have written my Class 11 exams and know I will pass. I have to finish school and do a teacher-training course.” Maybe Vanavil is looking at a future addition to their teaching staff.

Cover photo: M. Palani Kumar