Three women from Mulshi taluka in Pune sing grindmill songs about the impact of a young and attractive woman’s behaviour on a married woman’s husband or son. They see in her a threat to their own happiness

Patriarchal society doesn’t just oppress women, it constantly pits them against one another. The grindmill songs cover a wide range of experiences of women who live in rural communities where the framework of patriarchy dictates every aspect of life. The women who sing these songs cry out in protest against society’s norms, where the birth of a girl child is a calamity for the parents. Their songs question why, when the sons and daughters are like oranges of the same tree, their treatment differs – and why the work that a woman performs holds no value. And yet, there are also songs which present marriage as the ultimate goal, the route to happiness for women.

The grindmill songs are a fine example of a cultural practice that connects and divides women, reproduces and questions a social order, and liberates and conditions a generation of singers and listeners. It is in this environment that friendship and a sense of sisterhood among women is celebrated – as many of the songs do.

However, there are also grindmill songs that reveal rivalries between women and reflect on them. Often, rivalry is presented as jealousy arising from women sharing the influence on a man – either a husband or a son. They give a succinct picture of the vulnerabilities that mark the lives of women, whose very existence depends on the recognition and attention that they get from the men in the family – a father or brother, and, as in the songs presented here

,

a husband and son.

In these

ovi

, an older, married, and therefore a respectable woman, is placed against a younger, unmarried woman who is looked upon with suspicion, especially because she is both attractive and outgoing. In the first three

ovi

, a woman – younger – is accused of indecent behaviour. To describe her actions, the verse alludes to a Marathi proverb: “A slanderous woman has let the water from the eaves seep into the thatched roof of a home.” Her wicked deeds are said to be so many that “a pot of water has been emptied … [and] the woman has slipped a tortoise into the well water.” The phrases imply the deliberate nature of her behaviour that destroys the happiness of another woman.

"Guavas float in her pitcher, as the woman goes to fetch water, My son jokes with her, to provoke smiles and laughter"

In the next 14 couplets, the singer elaborates on the conduct of a woman in the prime of her youth. The narrator fears that her husband might fall prey to the younger woman’s beauty. The wife, therefore, tries to diminish her attractiveness by saying, “Your youth is only worth as much as my saree… [or] my toe-ring.” The singer also comments on her son’s attempt at flirting with the young woman. She speaks of this with affectionate indulgence, by addressing her son as raaghu (parrot), a term of endearment used in the grindmill songs to refer to a son or younger brother.

The last two longer stanzas stand out from the previous 17 couplets. Here, the woman wants to find a solution to the many distractions in her son’s life. Comparing her son to a tiger who cannot be tamed or tied to a chain, the narrator ardently wishes to get him married. She wants to welcome his bride, her daughter-in-law, into their home. This will elevate her own stature as the mother-in-law and bestow her with some authority over the younger woman. Hidden, perhaps, is a need to protect her son from getting into relationships outside the traditional, marital and patriarchal structure. Or an innocent belief of a mother that marriage will keep her son from straying.

Several of these

ovi

end with a phrase “

na bai…

” which communicates the conversational nature of these songs. Very much like the words “you know what happened …” It is as if the singer is sharing the stories within the songs with other women at the grindmill.

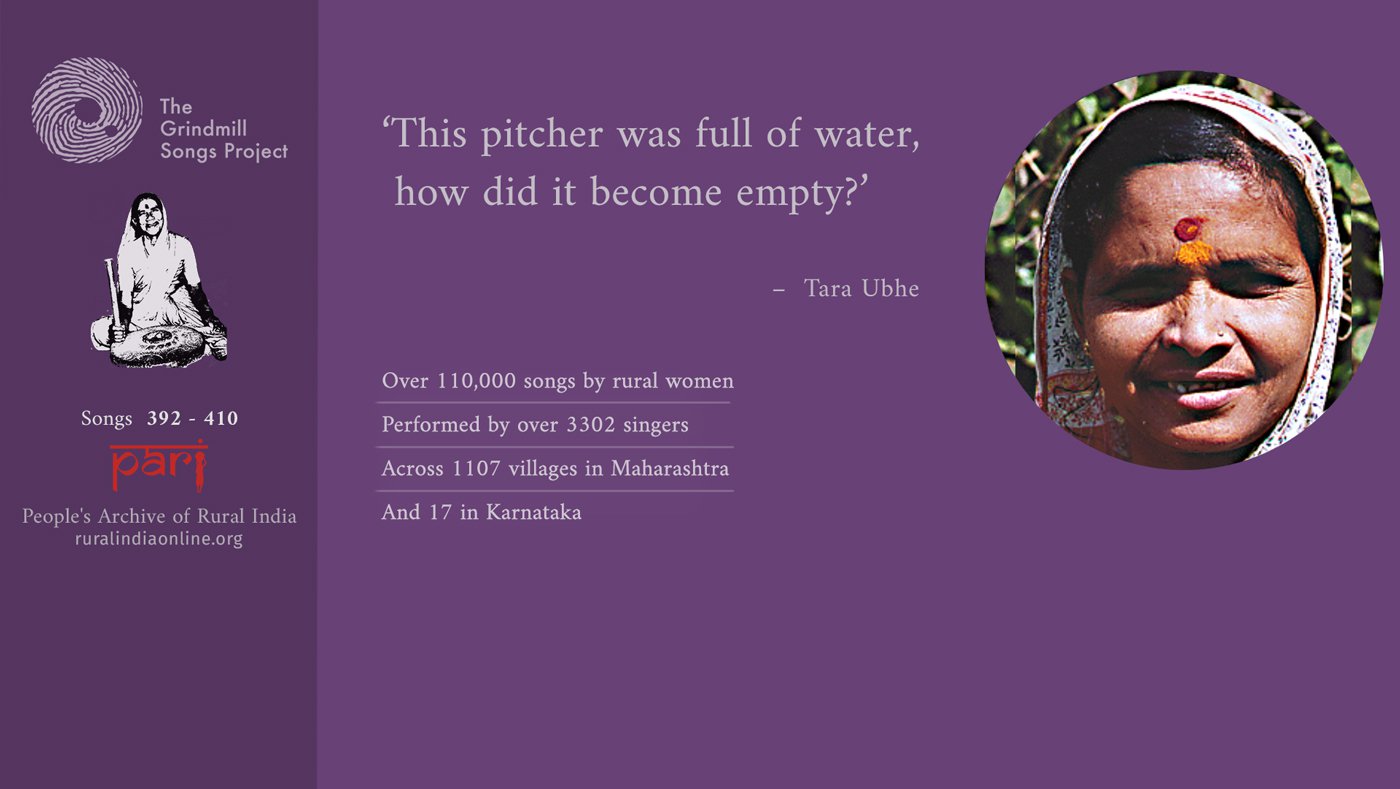

Three singers from Mulshi

taluka

of Pune district sang these nineteen

ovi

: Kusum Sonawane and Shahu Kamble of Nandgaon village, and Tara Ubhe of Khadakwadi hamlet in Kolavade village. The songs were recorded on October 5, 1999 in Pune, in the meeting room at the bungalow of Hema Rairkar and Guy Poitevin, founders of the original Grindmill Songs Project.

अभांड नारीनी, हिनी कुभांड जोडिलं

वळचणीचं पाणी हिनं आढ्याला काढियलं, ना बाई

अशी अभांड नारीनी हिची कुभांड झाली किती

ही गं भरली घागयीर ही गं कशानी झाली रिती

असं अभांड नारीनी, हिनी कुभांड जोडिलं

असं भरलं बारवत, हिनी कासव सोडिलं, ना बाई

नवनातीच्या नारी, माझ्या वाड्याला घाली खेपा

असं पोटीचा माझा राघु, माझा फुलला सोनचाफा, ना बाई

अशी नवतीची नारी उभी राहूनी मशी बोल

तुझ्या नवतीचं मोल, माझ्या लुगड्याला दिलं, ना बाई

नवतीची नारी, झाली मजला आडयेवी

तुझ्या नवतीचं मोल, माझ्या पायाची जोडयवी, ना बाई

नवनातीची नारी, नवती करिती झणुझणा

नवती जाईल निघुनी, माशा करतील भणाभणा, ना बाई

बाई नवनातीची नारी, खाली बसुनी बोलाईना

अशी बांडाचं लुगईडं, तुझ्या जरीला तोलाईना, ना बाई

नवतीची नारी नवती कुणाला दावियती

कशी कुकवानाच्या खाली, काळं कशाला लावियती, ना बाई

नवतीची नारी तुझी नवती जालीम

तुझ्या ना वाटंवरी, माझ्या बाळाची तालीम, ना बाई

नवनातीच्या नारी नवती घ्यावीस आवरुनी

अशी पोटीचं माझं बाळ, बन्सी गेलेत बावरुनी, ना बाई

पाण्याला जाती नार, हिच्या घागरीमधी पेरु

अशी तिला ना हसायला, बाळ माझं थट्टाखोरु

नवतीची नार, माझ्या वाड्याला येती जाती

बाई माझ्या ना बाळाची, टोपी वलणीला पहाती

अशी नार जाती पाण्या, येर टाकूनी टाक्याईला

अशी पोटीचं माझं बाळ, उभा शिपाई नाक्याला

अशी नार जाती पाण्या, येर टाकूनी बारवंला

अशी नवतीचा माझा बाळ, उभा शिपाई पहाऱ्याला

नवतीची नार, माझ्या वाड्याला येती जाती

बाई आता ना माझा बाळ, घरी नाही सांगू किती, ना बाई

अशी माझ्या ना अंगणात, तान्ह्या बाळाची बाळुती

अशी वलांडूनी गेली, जळू तिची नवती

नवतीच्या नारी गं, नको हिंडूस मोकळी गं

आणा घोडं, करा साडं, जाऊ द्या वरात

बाळा माझ्याची नवरी गं येऊ द्या घरात (2)

बाळाला माझ्या गं, नाही वाघ्याला साखळी गं

अगं रखु, काय गं सांगू, काही बघतं

दाऱ्यावर चंद्र जनी गं, लगीन लागतं

आणा घोडं, करा साडं, जाऊ द्या वरात

बाळा माझ्याची नवरी गं येऊ द्या घरात (2)

abhāṇḍa nārīīnī, hini kubhāṇḍa jōḍīla

vaḷacaṇīcaṁ pāṇī hini āḍhyālā kāḍhīyīla nā bāī

asaṁ abhāṇḍa nārīnī kubhāṇḍa jhālī kitī

hī ga bharalī ghāgayīra hī ga kaśānī jhālī rītī

abhāṇḍa nārīīnī, hini kubhāṇḍa jōḍīla

vaḷacaṇīcaṁ pāṇī hini kāsava sōḍīla, nā bāī

navatīcyā nārī, mājhyā vāḍyālā ghālī khēpā

āsa pōṭīcā mājhā rāghu, mājhā phulalā sōnacāphā, nā bāī

aśī navatīcī nārī ubhī rāhūnī majaśī bōla

tujhyā navatīca mōla, mājhyā lugaḍyālā dila, nā bāī

navatīcī nārī jhālī majalā āḍayēvī

tujhyā navatīca mōla, mājhyā pāyācī jōḍayavī, nā bāī

navanātīcī nārī navatī karītī jhaṇujhaṇā

navatī jāīla nighūnī, māśā karatīla bhaṇābhaṇā, nā bāī

bāī navanātīcī nārī khālī basūnī bōlāīnā

aśī bāṇḍāca lugīḍa tujhyā jarīlā tōlāīnā, nā bāī

navatīcī nārī navatī kuṇālā dāvīitī

kaśī kukavānācyā khālī, kāḷa kaśālā lāvīītī, nā bāī

navatīcī nārī tujhī navatī jālīma

tujhyā nā vāṭavarī, mājhyā bāḷācī tālīma, nā bāī

navanātīcyā nārī navatī ghyāvīsa āvarunī

aśī pōṭīcaṁ mājhaṁ bāḷa bansī gēlēta bāvarunī, nā bāī

pāṇyālā jātī nārī hicyā ghāgarīmadhī pēru

aśī tilā nā hasāyalā bāḷa mājhaṁ thaṭṭākhōru

navatīcī nāra, mājhyā vāḍyālā yētī jātī

bāī mājhyā nā bāḷācī, ṭōpī valaṇīlā pahātī

aśī nāra jātī pāṇyā yēra ṭākūnī ṭākyāīlā

aśī pōṭīca mājha bāḷa ubhā śipāī nākyālā

aśī nāra jātī pāṇyā, yēra ṭākūnī bāravalā

aśī naṭavīcā mājhā bāḷa, ubhā śipāī pahāryālā

navatīcī nāra mājhyā vāḍyālā yētī jātī

bāī bāī mājha bāḷa, gharī nāhī sāṅgū kitī, nā bāī

aśī mājhyā nā aṅgaṇāta, tānhyā bāḷācī bāḷutī

aśī valāṇḍūnī gēlī, jaḷū ticī navatī

āṇā ghōḍaṁ karā sāḍaṁ jā'ūdyā varāta

bāḷā mājhyācī navarī gaṁ yē'ūdyā gharāta (2)

bāḷālā mājhyā gaṁ, nāhī vāghyālā sākhaḷī gaṁ

agaṁ rakhu, kāya gaṁ sāṅgū, kāhī baghataṁ

dāṟyāvara candra janīṁ gaṁ, lagīna lāgataṁ

āṇā ghōḍaṁ, karā sāḍaṁ, jā'ūdyā varāta

bāḷā mājhyācī navarī gaṁ yē'ūdyā gharāta (2)

The slanderous woman, her behaviour is outrageous, for sure

She took water of the eaves to the thatched roof, the evil-doer

The notorious woman, very often she behaved indecently

This pitcher was full of water, how did it become empty?

The slanderous woman, so many times she behaved salaciously

Friends, what could I say, she released a tortoise into the well, slyly

A young woman in the prime of her youth, frequents my home

My son, my

raaghu

, is youthful like a golden

champak

blossom

O woman in the prime of youth, stand here and talk to me

For me, your youth is not worth a whit more than my saree

The young attractive woman, who has crossed me

The value of your youth is the same as my toe-rings

O woman full of youthful beauty, don’t be so showy

Flies will hover over you, when your youth fades away

Speaking to me, the young woman doesn’t care to be humble

Her brocade saree is not comparable to mine, which is simple

O young woman, to whom do you show off your youth?

Why do you apply a black spot below your

kunku

?

O young woman, you are attractive, your beauty is

jaalim

[strong]

Beware, along the path you go to fetch water, is my son’s

taalim

[gymnasium]

O young woman, tone down your youthful attraction

The son of my womb, Bansi, is filled with confusion

Guavas float in her pitcher, as the woman goes to fetch water

My son jokes with her, to provoke smiles and laughter

She frequents my house, the young woman in her prime

O woman, she looks for my son’s cap on the clothes line

The woman goes to the tank, not the well, to fetch water

My son, as alert as a soldier, is waiting at the corner

The woman goes to fetch water, to the draw-well, not the well

Like a guard on watch-duty, my son is standing there

She frequents my house, the young woman in her prime

I am fed up, how often do I tell her, my son is not at home

My baby’s clothes are drying in my home’s courtyard

She [barren woman] crosses them, let her youth burn

O young woman don’t wander about freely

Fetch the horse, decorate it, let the wedding procession go

Let me welcome my son’s bride into my home

My brave young son, like a tiger, has no leash

O Rakhu, what can I tell you, he is so distracted [by women],

Even on the wedding day, as the ceremony goes on

Fetch the horse, decorate it, let the wedding procession go

Let me welcome my son’s bride into my home

Performer/Singer: Tarabai Ubhe

Village: Kolavade

Hamlet : Khadakwadi

Taluka: Mulshi

District: Pune

Caste: Maratha

Age: 70

Children: Three daughters

Occupation: Farmer. Her family owns one acre of land and grows rice, wheat, ragi and some little millet.

Performer/Singer: Kusum Sonawane

Village: Nandgaon

Taluka: Mulshi

District: Pune

Caste: Nav Bauddha (Neo Buddhist)

Age: 73

Children: Two sons and two daughters

Occupation: Farmer

Performer/Singer: Shahu Kamble

Village: Nandgaon

Taluka: Mulshi

District: Pune

Caste: Nav Bauddha (Neo Buddhist)

Age: 70 (She died in August 2016 of uterine cancer)

Children: Two sons and two daughters

Occupation:

Farmer

Date: These songs were recorded on October 5, 1999.

Poster: Urja

Read about the original Grindmill Songs Project founded by Hema Rairkar and Guy Poitevin.