As the capital city lit up on Friday warmly welcoming global leaders for the G20 summit, the world has turned dark for those who live on Delhi's margins: the displaced farmers, now the Yamuna flood refugees, who have been quickly shunted out of sight. They have been sent away to forested areas along the banks of the river, away from their makeshift spots under the Geeta Colony flyover, and told to hide there for the next three days.

"Some of us have been forcefully removed by the police. Told to vacate within 15 minutes else they will remove us with force and power," Hiralal told PARI.

There are snakes, scorpions and other dangers lurking in the high grass of the forested area. "Our families are without electricity and water. If anyone gets bitten or stung, there is no medical help," points out the once proud farmer.

*****

Hiralal rushed to pick up the family’s cooking cylinder. The 40-year-old was taking no chances as dark waters snaked around furiously, rushing into his home in Bela Estate, located close to Rajghat in Delhi.

It was the night of July 12, 2023. Days of heavy rains had caused the Yamuna river to rise, and those like Hiralal who lived on its banks in Delhi, had run out of time.

Chameli, 60, (who goes by the name Geeta), a resident of Yamuna Pushta area in Mayur Vihar, hurriedly scooped up Rinky, her young neighbour’s tiny one month-old baby. Meanwhile all around her, people were ferrying frightened goats and dazed dogs on their shoulders, losing several on the way. Hapless residents were gathering utensils and clothes before the rising and swiftly flowing water took all their belongings.

“By morning, the water was everywhere. There were no boats to rescue us. People ran to the flyovers, wherever they could find dry land,” said Shanti Devi, 55, Hiralal’s neighbour in Bela Estate. “Our first thought was to keep our children safe; the murky waters could have snakes and other creatures not visible in the dark.”

She watched helplessly as their food rations and children’s schoolbooks floated away in the water. “We lost 25 kg of wheat, clothes drifted off…”

A few weeks later, at their makeshift homes under the Geeta Colony flyover, the displaced survivors spoke to PARI. “ Prashaasan ne samay se pehle jagah khaali karne ki chetaavni nahin di. Kapde pehle se baandh ke rakhe the, god mein utha-utha ke bakriyan nikaalin… humne naav bhi maangi jaanwaron ko bachaane ke liye, par kuch nahin mila [The authorities didn’t even make an announcement to tell us to move out in time. We’d already tied up our clothes, rescued as many goats as we could, we asked for a boat to save our animals but got nothing],” said Hiralal, speaking in early August.

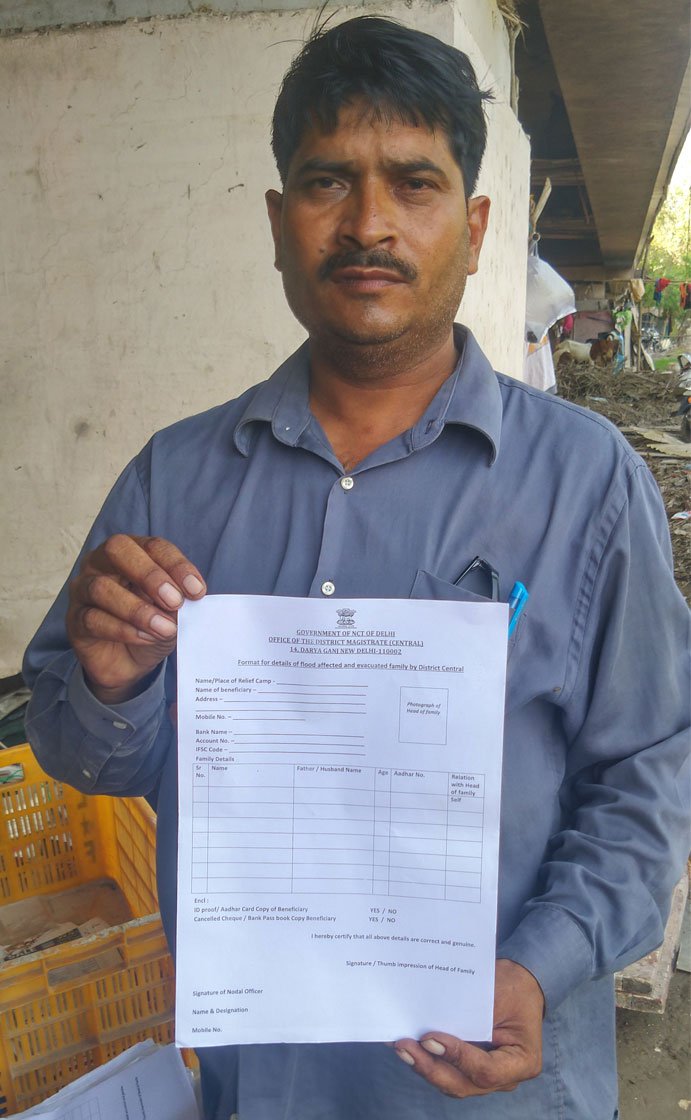

Hiralal is a resident of Bela Estate who has been displaced by the recent flooding of the Yamuna in Delhi. He had to rush with his family when flood waters entered their

home in July 2023. They are currently living under the Geeta Colony flyover near Raj

Ghat (right) with whatever belongings they could save from their flooded homes

Geeta (left), holding her neighbour’s one month old baby, Rinky, who she ran to rescue first when the Yamuna water rushed into their homes near Mayur Vihar metro station in July this year. Shanti Devi (right) taking care of her grandsons while the family is away looking for daily work

Hiralal and Shanti Devi’s families have been living under the Geeta Colony flyover for almost two months now. They are compelled to intercept streetlights for their basic electricity needs in their makeshift spot under the flyover – just to light a bulb at night. Twice a day, Hiralal lugs 20 litres of drinking water on his cycle from a public water tap located in Daryaganj, 4 to 5 kilometres away.

They have not received any compensation for rebuilding their lives, and Hiralal, once a proud farmer on the banks of the Yamuna, is working as a construction labourer; his neighbour, Shanti Devi’s husband, Ramesh Nishad, 58, also a former farmer, is now standing in a long line of kachori (snack) sellers hawking wares on a busy road.

But even this immediate future is thrown into jeopardy as the government and Delhi gear up for hosting the G20 meet. Hawkers have been ordered to clear off for the next two months. “Do not be seen,” is what the authorities say. “How will we eat?” asked Shanti. “In the name of showing off to the world, you’re destroying the homes and livelihoods of your own people.”

On July 16, the Delhi government announced Rs. 10,000 relief to each flood affected family. On hearing the sum, Hiralal was incredulous. “What kind of compensation is this? On what basis did they come to this figure? Is 10,000 rupees what our lives are worth? One goat costs 8,000-10,000 [rupees]. It takes 20,000-25,000 [rupees] to build even a makeshift home.”

Like many others who live here, and lost the land they once cultivated, are now doing mazdoori (daily wage work), pulling rickshaws or desperately seeking domestic work. “Was a survey done to determine who lost how much?” they ask.

Several families in

Bela Estate, including Hiralal and Kamal Lal (third from right), have been

protesting since April 2022 against their eviction from the land they cultivated and which local authorities are eyeing for a biodiversity park

Most children lost their books (left) and important school papers in the Yamuna flood. This will be an added cost as families try to rebuild their lives. The solar panels (right) cost around Rs. 6,000 and nearly every flood-affected family has had to purchase them if they want to light a bulb at night or charge their phones

Six weeks later the waters have receded but not everyone has received compensation. Residents blame the excessive paperwork and circuitous processes: “First they said get your Aadhaar card, bank papers, photos, then they asked for ration cards…,” said Kamal Lal. He is not even sure if the money will eventually come for the 150-odd families in the area – victims of a man-made disaster which could have been averted.

Previous attempts at seeking rehabilitation for the 700-odd old farming families living in the area who lost their farming land to state projects, have not moved forward. There is a constant ongoing tussle with authorities who want them to clear off. Whether ‘development’, displacement, disaster or display, these farmers have always been the casualties in the scheme of things. Kamal is part of the Bela Estate Mazdoor Basti Samiti group that has been asking to be compensated but, “the floods halted our protests,” says the 37-year-old, wiping off the sweat on a humid August afternoon at the site.*****

It is after 45 years that Delhi was drowning again. In 1978 Yamuna rose 1.8 metres above its official safety level, touching 207.5 mts; this year in July, it crossed 208.5 mts – an all-time record. The barrages in Haryana and Uttar Pradesh were not opened in time and the swollen river flooded Delhi resulting in loss of lives, homes and livelihoods; crops and other water bodies also suffered extensive damage.

During the floods in 1978, the Irrigation and Flood Control Department of the Government of NCT of Delhi noted, ‘damages were estimated at nearly Rs. 10 crore, 18 lives were lost and thousands of people were rendered homeless.’

Homes that were flooded near Pusta Road, Delhi in July 2023

Flood waters entered homes under the flyover near Mayur Vihar metro station in New Delhi

This year, after several days of rain in July that led to the floods, a PIL plea claimed that over 25,000 people were directly or indirectly affected. According to the Yamuna River Project : New Delhi Urban Ecology, steady encroachment of the floodplain will have severe consequences, “… wiping out structures built in low lying areas of the floodplain and inundating east Delhi with water.”

Around 24,000 acres have been cultivated on the banks of the Yamuna and farmers have been farming here for more than a century. But the concretisation of the floodplains – temple, metro station, Commonwealth Games Village (CWG) – has left less and less ground for flood waters to settle. Read: Big city, small farmers, and a dying river

“Nature will chart its course no matter what we do. Earlier the water spread out during rains and floods, and now because there’s less space [in the floodplains], it was forced to rise to flow, and in the process destroyed us,” added Kamal of Bela Estate – those who are paying the price for the 2023 floods. “Saaf karni thi Yamuna, lekin humein hi saaf kar diya [They were supposed to clean the Yamuna but instead cleaned us out]!”

“Yamuna ke kinaare vikas nahin karna chaahiye. Yeh doob kshetra ghoshit hai. CWG, Akshardham, Metro yeh sab prakriti ke saath khilwaad hai. Prakriti ko jitni jagah chaahiye, woh toh legi. Pahle paani failke jata tha, aur ab kyunki jagah kam hai, toh uth ke ja raha hai, jiski wajah se nuqsaan humein hua hai [The area of the floodplains close to the Yamuna should not be developed. It’s already designated as a flood-prone area. Building the CWG, Akshardham temple, metro station in the floodplains is like playing with nature,” adds Kamal.

“ Dilli ko kisne dubaya [who drowned Delhi]? The Delhi government’s Irrigation and Flood Control Department is supposed to prepare every year between June 15-25. Had they opened the barrage gates [in time], the water wouldn’t have flooded like this. Paani nyaaya maangne Supreme Court gaya [the water reached the Supreme Court as if to ask for justice],” said Rajendra Singh, not in jest.

Small time cultivators, domestic help, daily wage earners and others had to move to government relief camps like this one near Mayur Vihar, close to the banks of Yamuna in Delhi

Left: Relief camp in Delhi for flood affected families. Right: Experts including Professor A.K. Gosain (at podium), Rajendra Singh (‘Waterman of India’) slammed the authorities for the Yamuna flood and the ensuing destruction, at a discussion organised by Yamuna Sansad

The Alwar-based environmentalist pointed out that, “this was not a natural disaster. Erratic rainfall has happened earlier too,” while addressing a public discussion, ‘Delhi’s Floods: Encroachment or Right?’ on July 24, 2023. It was organised in Delhi by Yamuna Sansad, a people’s initiative to save the Yamuna from pollution.

“Heads should be rolling given what happened with the Yamuna this year,” said Dr. Ashvani K. Gosain at the discussion. He was an expert member of the Yamuna Monitoring Committee set up by the National Green Tribunal in 2018.

“Water has velocity too. Without embankments, where will the water go?” asks Gosain, who advocates building reservoirs instead of barrages. An emeritus Professor of civil engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi, he points out that the 1,500 unauthorised colonies as well as lack of street level drains send water into sewer lines, and “this brings diseases too.”*****

The Bela Estate farmers have already been living precariously with climate change, their cultivation halted, no rehabilitation and under threat of evictions. Read: ‘In the capital, this is how farmers are treated’ . The recent floods are just the latest in a series of losses.

“For one family of 4-5 people living in a 10 x 10 jhuggi [makeshift home], the cost is 20,000-25,000 rupees to build one. The waterproofing sheet alone costs 2,000 rupees. If we hire labour to build our homes, we have to pay 500-700 [rupees] per day. If we do it ourselves and lose our own day’s wage,” says Hiralal who lives with his wife and four children, aged 17, 15, 10, 8. Even bamboo poles cost Rs. 300 each, and he says he will require at least 20 of them. Displaced families are unsure as to who is going to compensate them for their losses.

Hiralal says the flood relief paperwork doesn’t end and moreover the relief sum of Rs. 10,000 for each affected family is paltry, given their losses of over Rs. 50,000. Right: Shanti Devi recalls watching helplessly as 25 kilos of wheat, clothes and children’s school books were taken away by the Yamuna flood

The makeshift homes of the Bela Esate residents under the Geeta Colony flyover. Families keep goats for their domestic consumption and many were lost in the flood

Then there is the cost of restocking their livestock, many of whom were lost in the floods. “A buffalo costs anything upwards of 70,000 [rupees]. You have to feed it well for it to stay alive and give milk. A goat that we keep for the daily milk requirement of our children and tea costs 8,000-10,000 rupees to buy,” he adds.

His neighbour, Shanti Devi told PARI that after her husband lost his fight to be identified as a landowner and cultivator on the banks of the Yamuna, he sells kachoris on a bicycle but barely manages to make Rs. 200-300 a day. “The police take 1,500 rupees per cycle every month whether you stand there for three days or 30 days,” she points out.

The flood waters have receded, but other dangers lurk: vector-borne diseases like malaria, dengue and waterborne diseases such as cholera and typhoid pose a threat while over 100 cases of eye flu per day were being reported in the immediate aftermath at the relief camps which have since then been dismantled. Hiralal was nursing a red eye when we met him. He held up a pair of overpriced sunglasses: “These are worth 50 but sold for 200 rupees because of the demand.”

Speaking for the families who await compensation that won’t even be enough he adds with a wry smile, “The story is not new, people always profit from others’ pain.”

This story has been updated on September 9, 2023.