“My five-year-old daughter is running a high temperature,” says Shakieela Nizamuddin, “but the police stopped my husband [from taking her to the doctor]. He got scared and came back. We are not allowed to go outside our colony, not even to the hospital.”

Shakieela, 30, lives in the Citizen Nagar relief colony in Ahmedabad city. She scrapes out a living from making kites at home. She and her husband, a daily wage worker, are seeing their hopes dwindle along with their income under the lockdown. “The clinic is closed,” she told me on a video call. “They tell us to ‘go home, take some home remedies’. If want to go to the hospital, the police ask for files and documents. Where do we go to get all those?”

The people of this colony – one of 81 set up in Gujarat by charitable organisations in 2004 to house over 50,000 people displaced by the devastating communal violence of 2002 – are having a nightmarish time under lockdown.

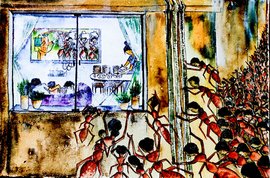

But also watching Amitabh Bachchan, as one of them tells me, on their television screens, urging everyone to come together and stop the novel coronavirus from spreading across India.

"If all we get to do is to sit inside our houses with folded arms, what should we wash our hands for?” asks Reshma Saiyad, affectionately called Reshma aapa , a community leader of Citizen Nagar. This is a rehabilitation colony for 2002 riot victims from Naroda Patiya, one of 15 in Ahmedabad. The stone slab at the colony’s gate says it came up in 2004 with the help of the Kerala State Muslim Relief Committee. That was when the first 40 families came here, riot survivors who had seen all their belongings torched to ashes two years earlier.

In Citizen Nagar, the threat the coronavirus brings is not just that infection, but also a heightened hunger and lack of access to medical help

Now there are around 120 Muslim families here. And hundreds more in immediately adjacent Mubarak Nagar and the Ghasia Masjid area – all part of a larger ghetto that existed prior to 2002. Their numbers also swelled with riot refugees around the same time Citizen Nagar came into being.

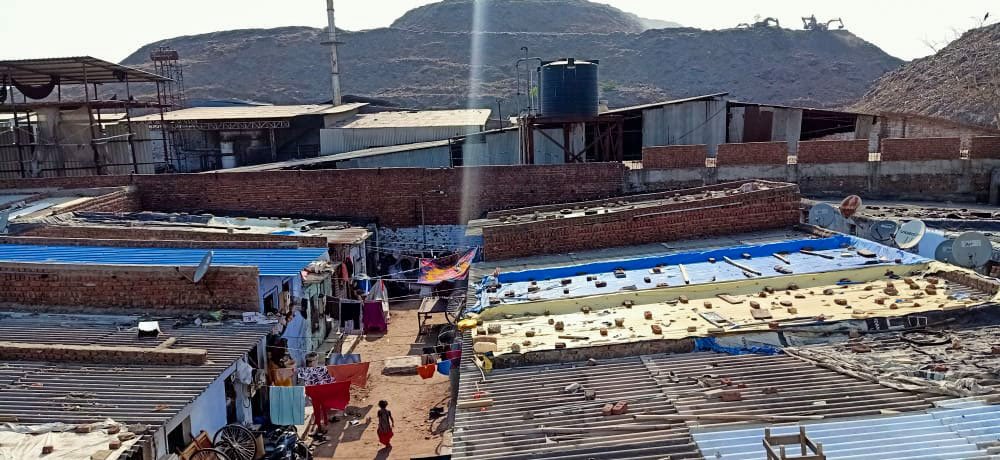

Citizen Nagar lies at the foothills of the infamous Pirana ‘garbage mountain range’. The landfill has been Ahmedabad’s major dumping ground since 1982. Spread over 84 hectares, it is best recognised by several massive mounds of garbage, some over 75 metres high. Pirana is estimated to hold 85 lakh metric tons of garbage – and known for the toxic fumes it often releases over the city.

It has been seven months since the National Green Tribunal gave the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) a one-year deadline to clear the garbage. With barely 150 days to go, there seems to be a single trammel machine at work in the landfill – just one of 30 that were supposed to be there.

Meanwhile, fires break out from mini-volcanic eruptions every now and then, releasing huge smoke clouds. The colony pops up in the media when such events occur, with stories on the conditions of people living in houses they have no papers for, years after they were ‘resettled’ there. The Citizens of this Nagar have been breathing in poisonous gases at close range for over 15 years.

“There are lots of patients who come with hacking cough and cold complaints,” says Dr. Farhin Saiyad, who consults in the nearby Rahat Citizen Clinic run by charitable foundations and social activists for the community. “Breathing problems and lung infections are quite common in this area due to air pollution and hazardous gases afloat all the time. There are a huge number of tuberculosis patients in the colony as well,” says Saiyad. The clinic had to be shut down when the lockdown began.

For residents like Reshma

aapa

, Covid-19 hygiene guidelines advising them to frequently wash their hands seem to mock the helplessness of people in Citizen Nagar, where there is little or no clean water.

Around 120 families live in Citizen Nagar, a relief colony for 2002 riot victims at the foothills of the Pirana landfill in Ahmedabad

The threat the coronavirus brings to this colony is not just that of death or infection or illness – those already exist – but also a heightened hunger and lack of access to medical help in the wake of a complete lockdown.

“Most of us women work in small factories around here – plastic, denim, tobacco,” says 45-year-old Rehana Mirza. “And the factories are anyway unpredictable. They call you if there is work and relieve you if there is none.” Rehana, a widow, worked in a tobacco factory nearby and earned some Rs. 200 rupees a day after putting in 8 to 10 hours of work. That work stopped two weeks before the lockdown, and now there is no hope of finding any unless it is lifted. She has no money to buy food.

“There are no vegetables, no milk, no tea leaves,” Reshma aapa says, “and many are without food for a week now. They [the authorities] do not even allow the vegetable lorries to come from outside. They do not let the grocery shops near the area open. Many here are small vendors, auto drivers, carpenters, daily wage labourers. They cannot go out and earn. There is no money coming in. What will we eat? What are we to do?”

Farooq Sheikh, one among the many autorickshaw drivers in the colony, says, “I get the auto on rent for Rs. 300 a day. But I have no fixed income. Even on days when I don’t have good business, I have to pay the rent. Some days I also do some work in factories for money.” He earned on an average Rs. 600-700 a day after 15 hours of work with his auto, but got only 50 per cent or less in hand.

The sole earning member in a family of six, Farooq feels the heat of the lockdown and now the curfew in his area. “We earn and eat daily. Now we cannot go out and earn. The police beat us,” he says. “Some people do not even have water in their house. What sanitisers? What masks? We are poor people. We don’t have such fancy things. Pollution anyway is there every day. So is disease and illness.”

Left: 'Many are without food for a week now', says c ommunity leader Reshma aapa . Centre: Farooq Sheikh with his rented auto; he is feeling the heat of the lockdown. Right: Even the Rahat Citizen Clinic has been shut for the lockdown (file photo)

This area, with such appalling living conditions and hazards, was never given a primary health centre despite repeated requests for one. It was only in 2017 that the Rahat Citizen Clinic opened here, funded entirely through private donations and the efforts of people like Abrar Ali, a young professor of Ahmedabad University working on issues of health and education with the community. But it has not been easy to run the clinic. Ali has struggled to find the right doctors, willing donors and generous landlords. As a result, in two and half years the clinic has changed three locations and four doctors. And now even this clinic is closed due to the citywide lockdown.

Citizen Nagar is located within the AMC’s limits but receives no municipal water supply. The people here relied on private tankers until a borewell was drilled in 2009. But the borewell’s water was never potable. A study done by the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, showed extremely high content of salts, metals, chloride, sulphate and magnesium. At present, another borewell, drilled about six months ago, meets part of the colony’s need. But waterborne diseases and stomach infections continue to rage here. Women and children develop multiple skin diseases and fungal infections as a result of working with, and consuming, contaminated water.

The people of Citizen Nagar see the government as having socially distanced itself from them very long ago. The Covid-19 pandemic and the lockdown are like the proverbial last straw on the backs of already suffering communities. “Governments only offer words and want votes,” says Mushtaq Ali (name changed), a plumber living here. “No leader has shown any urgency to visit our areas, to see how we are doing till now. Of what use is such government? People [here] too understand their games.”

On the television set in Mushtaq’s one-room home, and on those of others in this congested colony, the familiar voice of Amitabh Bachchan exhorts them: “…don’t touch your eyes, nose, mouth unnecessarily…visit your nearest health facility or your doctor immediately if you have any of these symptoms…”