Even as he lay in a hospital bed in Sitapur, on oxygen and struggling for life, Ritesh Mishra’s cell phone kept ringing. The calls were from the State Election Commission and government authorities demanding that the sinking schoolteacher confirm he would show up for duty on May 2 – counting day in Uttar Pradesh’s panchayat polls.

“The phone would not stop ringing,” says his wife Aparna. “When I answered it and told the person that Ritesh is hospitalised and could not accept the duty – they demanded I send them a photograph of him on his hospital bed – as proof. I did so. I will send you that photograph,” she told PARI. And did.

What Aparna Mishra, 34, talks about most is how strongly she had urged her husband not to go for election work. “I had been telling him that from the moment his duty roster arrived,” she says. “But he kept repeating that election work cannot be cancelled. And that the authorities might even file an FIR against him if he did not report for duty.”

Ritesh died of Covid-19 on April 29. One of over 700 UP schoolteachers who died the same way after being on duty in the panchayat polls. PARI has the full list which now totals 713 – 540 men and 173 women teachers – with the toll still mounting. This is a state with nearly 8 lakh teachers in government primary schools – tens of thousands of whom were sent out for poll duty.

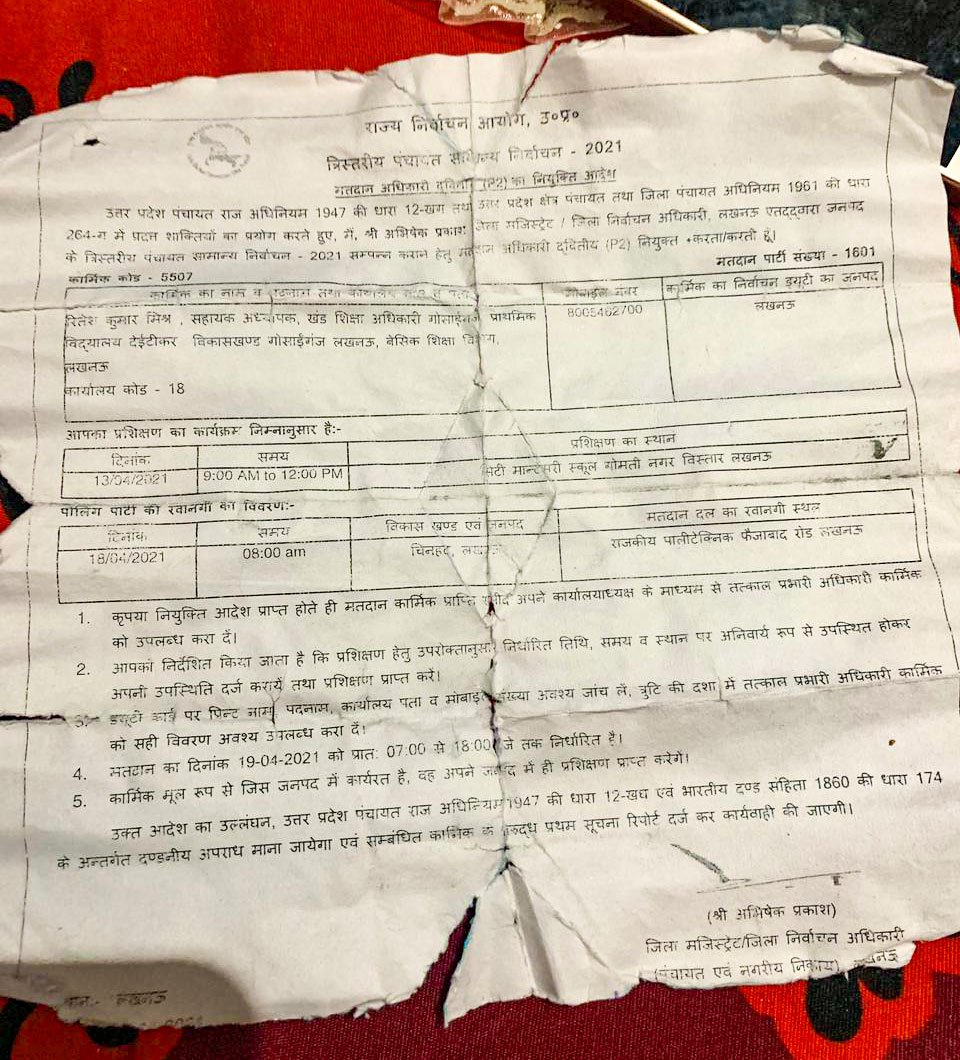

Ritesh, a sahayak adhyapak (assistant teacher) lived with his family in Sitapur district headquarters but taught at a primary school in Lucknow’s Gosaiganj block. He was assigned to work as a polling official at a school in a nearby village in the four-phase panchayat polls held on April 15, 19, 26 and 29.

'When I said Ritesh is hospitalised and could not accept the duty – they demanded I send them a photograph of him on his hospital bed – as proof. I did so. I will send you that photograph', says his wife Aparna. Right: Ritesh had received this letter asking him to join for election duty.

Panchayat polls in UP are a gigantic exercise and this one saw nearly 1.3 million candidates contesting over 8 lakh seats. With 130 million eligible voters entitled to choose candidates for four different directly elected posts, it involved printing 520 million ballot papers. Running this process held obvious risks for all polling officials.

The protests of the teachers and their unions against this form of duty, at the height of the coronavirus pandemic, were ignored. As the UP Shikshak Mahasangh (Teachers’ Federation) pointed out in a letter to the state election commissioner on April 12, there were no real protections, protocols on distancing or facilities to guard the teachers from the virus. The letter warned of the risks arising from the training, handling of ballot boxes, and from the teachers having to be in contact with thousands of people. The federation, therefore, called for a postponement of the polls. Further letters on April 28 and 29 pleaded for a deferment of the counting date.

“We had sent the letters to the State Election Commissioner by mail as well as by hand. But we never got any response or even acknowledgement,” Dinesh Chandra Sharma, president of the UP Shikshak Mahasangh told PARI. “Our letters went to the chief minister as well, but got no response.”

The teachers first went for a day’s training, then for two days of polling duty – one day for preparation and the second on the actual day of voting. Later, thousands were again required to report to count the votes. Fulfilling these tasks is mandatory. Having already done his day of training, Ritesh reported for polling duty on April 18. “He worked along with other government staff from different departments but did not know any of them from earlier,” says Aparna.

“I’ll show you the selfie he had sent me while on his way to the duty centre. It was a Sumo or Bolero in which he sat with two other men. He also sent me a photo of a similar vehicle which carried some 10 persons for election duty. I was petrified,” adds Aparna. “And then there was even more physical interaction at the voting booth.

Illustration: Jigyasa Mishra

The teachers first went for a day’s training, then for two days of polling duty – one day for preparation and the second on the actual day of voting. Later, thousands were again required to report to count the votes. Fulfilling these tasks is mandatory

“He returned home on April 19, after the voting, with a fever and a temperature of 103. He had called me before starting for home saying he was feeling unwell and I asked him to return quickly. For a couple of days we kept treating it like an ordinary fever due to exertion. But when the fever persisted on the third day (April 22), we consulted a doctor who asked him to immediately undergo a Covid test and a CT-scan.

“We got those done – he proved positive – and we raced around searching for a hospital bed. We must have checked at least 10 hospitals in Lucknow. After roaming around a full day, we finally got him admitted in a private clinic in Sitapur district, at night. He was having serious breathing problems by then.

“The doctor would come only once daily, mostly at 12 midnight, and no hospital staff responded whenever we called out to them. He lost his battle with Covid at 5:15 pm on April 29. He tried his best – we all tried our best – but he departed right in front of our eyes.”

Ritesh was the only earning member of his family of five, including himself, Aparna, their one-year-old daughter, and his parents. He and Aparna were married in 2013, and had their first child in April 2020. “We would have been celebrating our eighth wedding anniversary on May 12,” Aparna sobs, “but he left me before…” She is unable to complete the sentence.

*****

On April 26, a furious Madras High Court blasted the Election Commission of India (ECI) for allowing political rallies during the Covid-19 pandemic. Madras HC Chief Justice Sanjib Bannerjee told the ECI’s counsel: "Your institution is singularly responsible for the second wave of Covid-19." The Chief Justice went to the extent of orally saying " Your officers should be booked on murder charges probably."

The Madras HC was also angered at the Commission’s failure to enforce the wearing of face masks, use of sanitisers and maintaining social distancing during the poll campaigns, despite court orders.

At Lucknow’s Sarojini Nagar, May 2, counting day: Panchayat polls in UP are gigantic and this one saw nearly 1.3 million candidates contesting over 8 lakh seats

The next day, April 27, an angry Allahabad High Court Bench

issued a notice

to the UP State Election Commission (SEC) to show cause as to “why it had failed in checking non-compliance of Covid guidelines during various phases of the panchayat elections held recently and why action may not be taken against it and its officials for the same and to prosecute those responsible for such violations.”

With one phase of voting and the counting still to happen, the court ordered the SEC “to take immediately all such measures in forthcoming phases of panchayat elections to ensure that the Covid guidelines…of social distancing and face masking are religiously complied with, else action is liable to be taken against the officials involved in the election process.”

At that stage the number of deaths was understood to be 135 and the matter was taken up following a report on it by the daily Amar Ujala .

Nothing really changed.

On May 1, barely 24 hours before counting day, an equally irked Supreme Court asked the government : “Almost 700 teachers have died in this election, what are you doing about it?” (Uttar Pradesh had also just reported 34,372 cases of Covid-19 in just the previous 24 hours).

The reply of the Additional Solicitor General was: “States which have no election, they are also experiencing a surge. Delhi has no elections but even then there is a surge. When polling started we were not in midst of a second wave.”

In other words, the elections and polling had little to do with the deaths.

'The arrangements for safety of the government staff arriving for poll duty were negligible', says Santosh Kumar

“We do not have any authentic data which can show who was or who was not Covid positive,” UP minister of state for primary education Satish Chandra Dwivedi told PARI. “We have not got any audit done. Moreover, it’s not only the teachers who went for the duty and got positive. Also, how do you know they were not already corona positive, before going for their duty?” he asks.

However, a Times of India report cites official data as showing that “between January 30, 2020 and April 4, 2021 – in a span of 15 months – UP had recorded a total of 6.3 lakh Covid-19 cases. In 30 days starting April 4, over 8 lakh fresh cases took the caseload of UP to 14 lakh. The period was marked by the rural polls.” In other words, the state saw more Covid-19 cases in the single month of activity around the polls than it had in the entire run of the pandemic till then.

The list of 706 teachers who died was prepared on April 29 with the worst hit district being Azamgarh, which lost 34 of them. Also badly hit were the districts of Gorakhpur with 28 deaths, Jaunpur with 23, and Lucknow with 27. Lucknow district president of the UP Shikshak Mahasangh Sudanshu Mohan says the fatalities have not stopped. “In the past five days,” he told us on May 4, “seven more deaths have been recorded of teachers returning from poll duty.” (These names have been added to the list uploaded in the PARI Library).

However, while the tragedy of Ritesh Kumar gives us a glimpse of what at least 713 families are going through, it isn’t the whole story. There are also others presently battling Covid-19; those yet to be tested; and those who have been tested and await the results. There are even those who on returning have shown no symptoms so far but have self-quarantined. All their stories reflect the hard realities that had roused the anger and concern of the Madras and Allahabad High Courts and the Supreme Court.

“The arrangements for safety of the government staff arriving for poll duty were negligible,” says 43-year-old Santosh Kumar. He is headmaster of a primary school in Lucknow’s Gosaiganj block, and worked on both voting days as well as on counting day. “We all had to use buses or other vehicles arranged without any thought of social distancing. Then, at the venue, we got no gloves or sanitisers as precautionary measures. We only had what we took with us. In fact, the extra masks that we carried along ourselves we gave those to voters who turned up without their faces covered.

Illustration: Antara Raman

'I get calls from my

rasoiya

every second day and she tells me how the situation in her village is worsening. People there don’t even know what they are dying of'

“It’s true that we had no option of getting the duty cancelled,” he adds. “Once your name comes up in the roster, you have to go on duty. Even pregnant women had to go on poll duty, their applications for leave were rejected.” Kumar has so far experienced no symptoms – and has since taken part in the May 2 counting as well.

Mitu Awasthi, head of a primary school in Lakhimpur district, was more unlucky. The day she went for the training, she told PARI, she “found 60 others in the room. All of them from different schools of Lakhimpur block. They were all sitting, tightly packed, elbow to elbow, and practising on the one and only ballot box there. You cannot imagine how scary the whole situation was.”

Awasthi, 38, has since tested positive. She had completed her training – which she seems to hold responsible – and did not go for voting or counting duty. However, other staff from her school were assigned such work.

“One of our assistant teachers, Indrakant Yadav, was never given any election work in the past. This time he was,” she says. “Yadav was handicapped. He had just one hand and was still sent on duty. He fell ill within a couple of days of returning and eventually died.”

“I get calls from my rasoiya [school cook] every second day and she tells me how the situation in her village is worsening. People there don’t even know what they are dying of. They have little idea of the fever and cough they are complaining about – which could very well be Covid-19,” adds Awasthi.

Shiva K., 27, who has been a teacher for barely a year, works at a primary school in Chitrakoot’s Mau block. He got himself tested before he went on duty: “To be on the safer side, I got an RT-PCR test done before going on poll work and all was well.” He then reported for duty in Biyawal village of the same block on April 18 and 19. “But when I took a second test on returning from duty,” he told PARI, “I found I was Covid positive.”

Bareilly (left) and Firozabad (right): Candidates and supporters gathered at the counting booths on May 2; no distancing or Covid protocols were in place

“I assume I got infected in the bus which carried us from Chitrakoot district headquarters to the matdan kendra [voting centre]. There were at least 30 people in that bus, including police personnel.” He is undergoing treatment and is in quarantine.

A curious feature of the unfolding disaster was that though it was mandatory for the agents reaching the centre to have negative RT-PCR certificates, there was never any checking for that. Santosh Kumar, who has since done counting duty, says this and other guidelines were never followed at the centres.

*****

“We did write that letter on April 28 to the UP State Election Commission and also to chief minister Yogi Adityanath requesting a postponement of the counting from May 2,” says Shikshak Mahasangh president Dinesh Chandra Sharma. “The next day we gave that list of over 700 deaths to the SEC and the CM, which we compiled through the block level branches of our union.”

Sharma is aware of, but declines to comment on, the Madras High Court’s berating of the Election Commission of India. However, he says with great sadness that “our lives don’t matter because we are ordinary, not rich, people. The government didn’t want to upset the powerful by postponing the polls – as those people had spent huge sums of money on the elections already. Instead, we face unjust accusations on the figures we have provided.

“See here, ours is a 100-year-old union representing 300,000 government teachers from primary and upper primary schools. Do you think any union would have survived this long on the basis of lies and fraud?

“Not only have they refused to consider and accept our figures, they are setting up enquiries on those. For our part, we realise that this first list of 706 has missed many names. So we have to revise the list.”

Illustration: Jigyasa Mishra

He says with great sadness that 'our lives don’t matter because we are ordinary, not rich, people. The government didn’t want to upset the powerful by postponing the polls – as those people had spent huge sums of money on the elections already'

Lucknow district president of the Mahasangh Sudanshu Mohan told PARI, “We're also working on updating the list of teachers returning from counting duty who have tested Covid positive. There are many who have gone into 14-day precautionary quarantine on observing symptoms but who may not have tested yet.”

Dinesh Sharma points out that the union’s first letter demanded that “all personnel involved in the election processes are given enough tools to protect themselves from Covid-19.” That never happened.

“Had I known I would lose my husband this way, I wouldn’t have let him go. At worst, he could have lost his job, not his life,” says Aparna Mishra.

The first letter of the Shikshak Mahasangh to the authorities also sought that “any individual getting Covid-19 infection should get a minimum sum of 20 lakh rupees towards treatment. In case of accident or death, the family of the deceased should get a sum of 50 lakhs.”

If that happens it might bring some relief Aparna and many others whose partners or family members have lost their jobs as well as their lives.

Note:

According to news just in, the Uttar Pradesh government has told the Allahabad High Court it has “decided to give compensation of Rs.30,00,000/- to the family members of the deceased polling officers." However, the State Election Commission’s counsel

told the court

that the government only had reports of 77 deaths from 28 districts – so far.

Jigyasa Mishra reports on public health and civil liberties through an independent journalism grant from the Thakur Family Foundation. The Thakur Family Foundation has not exercised any editorial control over the contents of this reportage.