When Vikram didn’t return home that night, his mother Priya was not worried. He was working at a gharwali ’s house in another lane of Kamathipura and usually returned home by 2 a.m. or at times even the next morning if he slept over at his workplace.

She tried calling him, but there was no response. When he didn’t turn up even by the next evening, on August 8, she became anxious. She filed a missing persons complaint at the nearby Nagpada police station in central Mumbai. The next morning, the police began checking CCTV footage. “He was seen near a footbridge at Mumbai Central, near a mall,” says Priya.

Her anxiety escalated. “What if someone took him away? Has he got this naya bimari [Covid]?” she wondered. " No one cares what happens to anyone in this area,” she says.

Vikram though was on a journey of his own, one that he had planned in advance. His mother, a sex worker in her 30s, couldn’t work during the lockdown, and he had been seeing her financial condition crumbling and loans growing. His nine-year-old sister Riddhi was back home from her hostel in nearby Madanpura, and the family was subsisting on ration kits distributed by NGOs. ( All names in this story have been changed .)

And with the lockdown in March, the municipal school Vikram attended in Byculla too was closed. So 15-year-old Vikram began doing odd jobs.

The family needed Rs. 60-80 every day for kerosene to cook. They were struggling to pay rent for their tiny room in Kamathipura. They needed money for medicines, and to pay off older loans. Priya kept taking further loans from her clients or locals. Over some years, a loan from a moneylender, with interest, had spiralled to Rs. 62,000. And she has only been able to repay half portions, if even that, of the Rs. 6,000 monthly rent to the gharwali (landlady and brothel madam) for more than six months, plus has borrowed around Rs. 7,000 from her.

Vikram and his mother Priya had a fight on August 7 because she didn’t want him sleeping over at the gharwali’ s (madam's) rooms after work

Her income from sex work depends on the number of days she works, and ranged from Rs. 500 to Rs. 1,000 a day before the lockdown. “It was never regular. If Riddhi came back from the hostel, or if I was sick, then I took leave,” says Priya. Besides, she often cannot work due to a persistent and painful abdominal illness.

Sometime after the lockdown began, Vikram began standing near the deserted corner of their lane in Kamathipura, hoping a contractor would take him to construction sites for daily wage work. At times, he fitted tiles, sometimes built bamboo scaffolding or loaded trucks. And usually earned Rs. 200 a day. The highest he made was Rs. 900 for a double shift. But these jobs lasted only for a day or two.

He also tried selling umbrellas and masks on the streets in his neighbourhood. He would buy the items in wholesale, walking to Null Bazar around a kilometre away, using his previous earnings. If he fell short of money, he asked a local lender or his mother. A shopkeeper once asked him to sell earphones for a commission. “But I could not make a profit,” says Vikram.

He tried to sell tea to taxi drivers and others sitting around on the streets. “My friend came up with this idea when nothing worked. He made the tea and in a Milton thermos bottle I used to go around to sell it.” A cup for Rs. 5, of which he got Rs. 2, and managed to earn a profit of Rs 60 to Rs. 100 a day.

He also sold beer bottles from a local liquor store, and packets of gutkha (tobacco mix), to Kamathipura residents and visitors – these were in demand when shops were closed during the lockdown, and could bring decent profits. But the competition was tough, with many young boys trying to sell, the income was intermittent, and Vikram was afraid his mother would find out what he was doing.

Eventually, Vikram started working for a gharwali , cleaning and running grocery errands for the women living in the building. He earned up to Rs. 300 every two days, but this work too was intermittent.

Vikram took up various odd jobs once the lockdown began, selling tea, or umbrellas and masks, working at construction sites and eateries

In doing all this, Vikram had joined the army of child workers pushed into labour by the pandemic. A June 2020 paper titled Covid-19 and Child Labour: A rime of crisis, a time to act , by the ILO and UNICEF, lists India among the countries where children have stepped in to provide support due to the economic shock of parental unemployment in the pandemic. “Children below the minimum legal age may seek employment in informal and domestic jobs,” the paper notes, “where they face acute risks of hazardous and exploitative work, including the worst forms of child labour.”

After the lockdown, Priya too tried looking for a job, and in August she found one as a domestic worker in Kamathipura, earning Rs. 50 a day. But that lasted only for a month.

Then came Vikram’s fight with her, on August 7. They argued because Priya didn’t want him sleeping over at the gharwali ’s rooms after work. She was already on edge after a recent sexual assault of a minor in the vicinity, and was hoping to send Riddhi back to the hostel ( See ‘ Everyone knows what happens here to girls’ ).

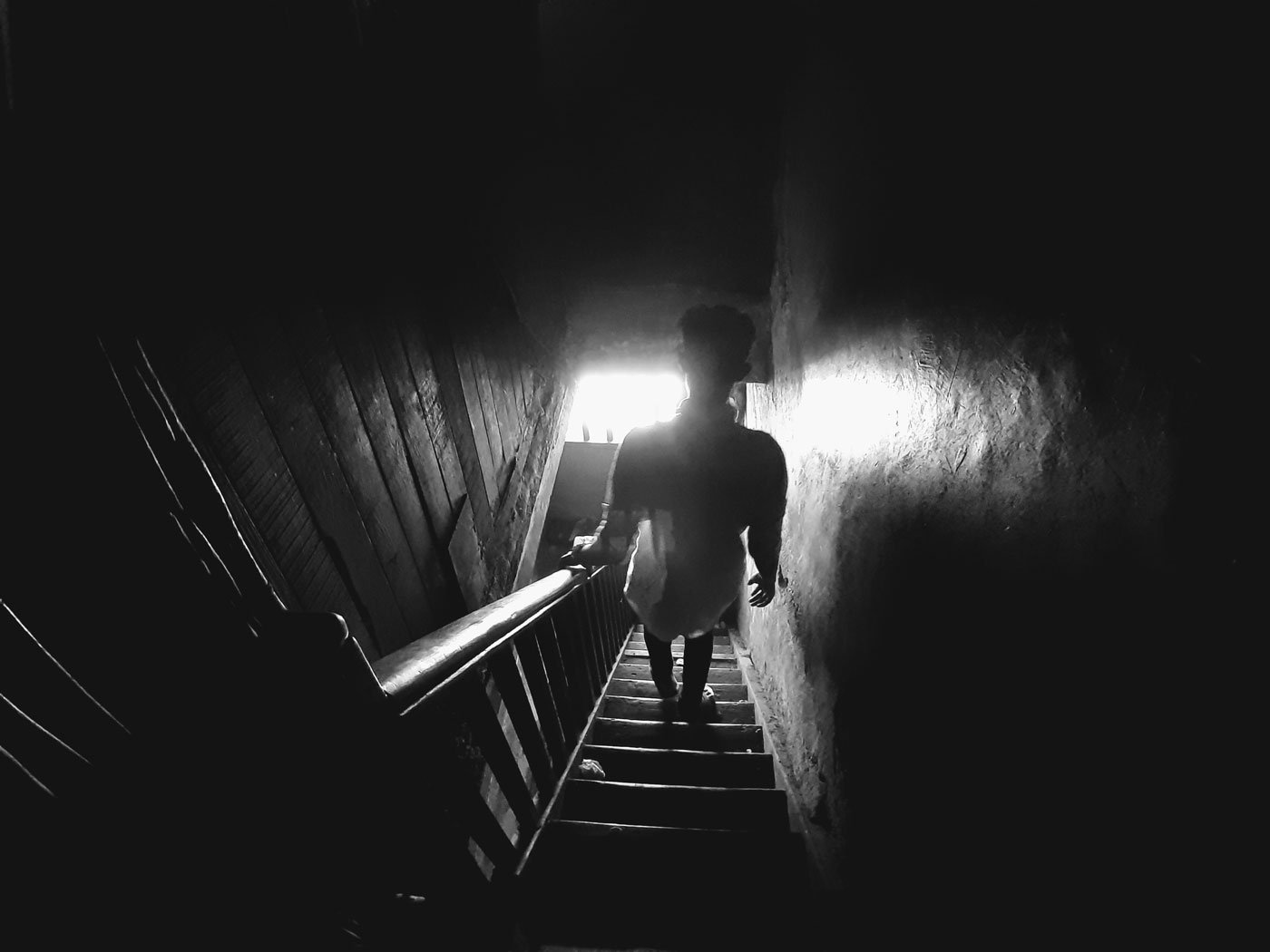

That afternoon, Vikram decided to leave. He had been planning it for some time, but only after talking about it with his mother. That day, he says, “I was angry and just decided to go.” He had heard from a friend that Ahmedabad had lucrative work options.

So with his small Jio phone and Rs. 100 in his pocket, around 7 p.m. on August 7, he set out for Gujarat.

He used more than half the money for buying five packets of gutkha for himself, and a glass of fruit juice and some food near Haji Ali. From there onwards, Vikram walked. He tried hitching a ride, but no one stopped. In between, he got onto a BEST bus for a short distance with some of the money he still had, Rs. 30-40. By around 2 a.m. on August 8, the exhausted 15-year-old boy reached a dhaba near Virar and spent the night there. He had covered around 78 kilometres.

The dhaba owner inquired if he had run away. Vikram lied that he was an orphan and was going to Ahmedabad for a job. “The dhabawala bhaiya advised me to return home, he said no one will give me a job, and during corona reaching Ahmedabad was difficult.” He gave Vikram some chai and poha and Rs. 70. “I thought of returning home but I wanted to go back with some earnings,” says Vikram.

'Many of my friends [in Kamathipura] leave school and work,' says Vikram, 'they feel earning is better as they can save and start a business'

He walked further and saw some trucks near a petrol pump. He asked for a lift, but no one agreed to take him for free. “There were buses in which a few families were sitting, but no one allowed me in after realising that I was coming from Mumbai [where many Covid cases were being reported].” Vikram pleaded with many until a tempo driver agreed “He was alone, he asked me if I was ill and took me in after I said no.” The driver too warned the teenager that he was unlikely to find work. “He was crossing Vapi so he agreed to drop me there.”

He reached Vapi in Gujarat’s Valsad district – some 185 kilometres from Mumbai Central – around 7 a.m. on August 9. From there, Vikram’s plan was to go on to Ahmedabad. That afternoon, he called his mother from someone’s phone. His own phone’s battery was drained and there was no call-time left either. He told Priya he is fine and in Vapi, and disconnected.

Meanwhile, in Mumbai, Priya was visiting the Nagpada police station regularly. “The police blamed me for being careless, commented on my work, and said that he left on his own own and would return soon,” she recalls.

After Vikram’s brief call, she frantically called back. But the owner of the phone responded. “He said he wasn’t with Vikram and had no idea where he was. He had met Vikram at a highway chai stall and had just lent his phone.”

Vikram stayed on in Vapi on the night of August 9. “A boy elder to me was guarding a small hotel. I told him that I was going to Ahmedabad for work and wanted to sleep somewhere. He said stay here at this hotel and work, he would talk to the malik .”

!['I too ran away [from home] and now I am in this mud,' says Vikram's mother Priya, a sex worker. 'I want him to study'](/media/images/05-20201009_142358-A.max-1400x1120.jpg)

'I too ran away [from home] and now I am in this mud,' says Vikram's mother Priya, a sex worker. 'I want him to study'

Four days after his first call to his mother, on August 13, Vikram made another call at 3:00 in the morning. He told her he had got a job in an eatery in Vapi, washing dishes and taking food orders. Priya hurried to inform the cops at Nagpada police station in the morning, but was asked to go get her son.

That evening, Priya and Riddhi took a train from Mumbai Central to Vapi to bring Vikram back. For this, Priya took a loan of Rs. 2,000 from a gharwali and a local lender. The train ticket cost Rs. 400 per person.Priya was determined to bring her son back. She does not want him to have an aimless life, like her own, she says. “I too ran away and now I am in this mud. I want him to study,” says Priya who, at around the same age Vikram is now, ran away from her home in Amravati district of Maharashtra.

She ran away from a drunk father, a factory worker, who didn’t care about her (her mother had died when she was two years old), relatives who beat her and tried to arrange her marriage when she was 12, and a male relative who had begun molesting her. “I had heard that I could get work in Mumbai,” she says.

After alighting from a train at Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, Priya eventually found a job in as a domestic worker in Madanpura, earning Rs. 400 a month and staying with the family. Over time, she lived with a man, a grocery shop worker, in a rented room in Reay Road in south Mumbai for some months, after which she says he disappeared. She started living on the streets and realised that she was pregnant. “I was begging and surviving.” Even after Vikram was born (in JJ Hospital in 2005) she stayed on the footpath. “One night, I met a dhandhewali who fed me. She explained that I have a child to feed, and I should join the trade.” With a lot of misgivings, Priya agreed.

At times, she would go to Bijapur in Karnataka for sex work along with a few women in Kamathipura who are from that town. On one such trip, they introduced her to a man. “They said he will marry me and I and my son will have a good life.” They had a private ‘wedding’ and for 6-7 months she stayed with him, but then his family asked her to leave. “That time Riddhi was due,” says Priya, who later realised the man was using a false name and was already married, and the women had ‘sold’ her to him.

After Riddhi was born in 2011, Priya sent Vikram to a relative’s house in Amravati. “He was growing up and seeing things around in this area…” But the boy ran away from there too, saying they beat him for indiscipline. “We had filed a missing complaint that time as well. After two days, he returned.” Vikram had taken a train and reached Dadar station, and stayed in empty train compartments eating what others gave thinking he was a beggar.

![Vikram found it hard to make friends at school: 'They treat me badly and on purpose bring up the topic [of my mother’s profession]'](/media/images/06-IMG_5382-A.max-1400x1120.jpg)

Vikram found it hard to make friends at school: 'They treat me badly and on purpose bring up the topic [of my mother’s profession]'

He was 8 or 9 years old then and was detained for ‘vagrancy’ in the juvenile home in Dongri in central Mumbai for a week. After that, Priya sent him to a hostel-plus-school in Andheri run by a charitable organisation, where he studied till Class 6.

“Vikram has always been in trouble. I have to be more careful with him,” Priya says. She had wanted him to remain in the hostel in Andheri (where he was even taken to a counsellor a few times), but he had run away from there too, after hitting a caretaker. In 2018, she enrolled him in the municipal school in Byculla, in Class 7, and he moved back to Kamathipura.Vikram has also been suspended from the Byculla school on and off for misbehaviour and picking fights with other boys. “He doesn’t like it when students and people around tease him about my work. He gets angry very quickly,” says Priya. He usually doesn’t tell anyone about his family, and finds it hard to make friends in school. “They treat me badly and on purpose bring up the topic [of my mother’s profession],” Vikram says.

He is a bright student though, with percentages usually in the 90s. But his Class 7 marksheet shows that at times he attended school for barely three days in a month. He says he can catch up with his studies and he does want to study. In early November 2020, he received his Class 8 marksheet (for the 2019-20 academic year) and has got an A grade in seven subjects, and a B in the remaining two.

“Many of my friends [in Kamathipura] leave school and work. Some have no interest in studying, they feel earning is better as they can save and start a business,” says Vikram. (A 2010 study of children living in the red-light areas of Kolkata notes a drop-out rate of nearly 40 per cent, and points out that "this highlights the unfortunate reality that low school attendance is one of the most common problems for children living in red light areas.”)

Vikram opens a gutkha packet while we are talking. “Don’t tell mother,” he says. Earlier he used to smoke and drink too occasionally, found it bitter and stopped But, he says, “I can’t shake off the gutkha habit . I tried it to taste and don’t know when I got used to it.” At times, Priya has caught him chewing it and beaten him.

“Children here pick up all the wrong habits, that is why I want them in a hostel, studying. Riddhi too imitates the women here,” says Priya, by trying to wear lipstick or imitating their walk. “Beating, fighting is all that you will see here every day.”

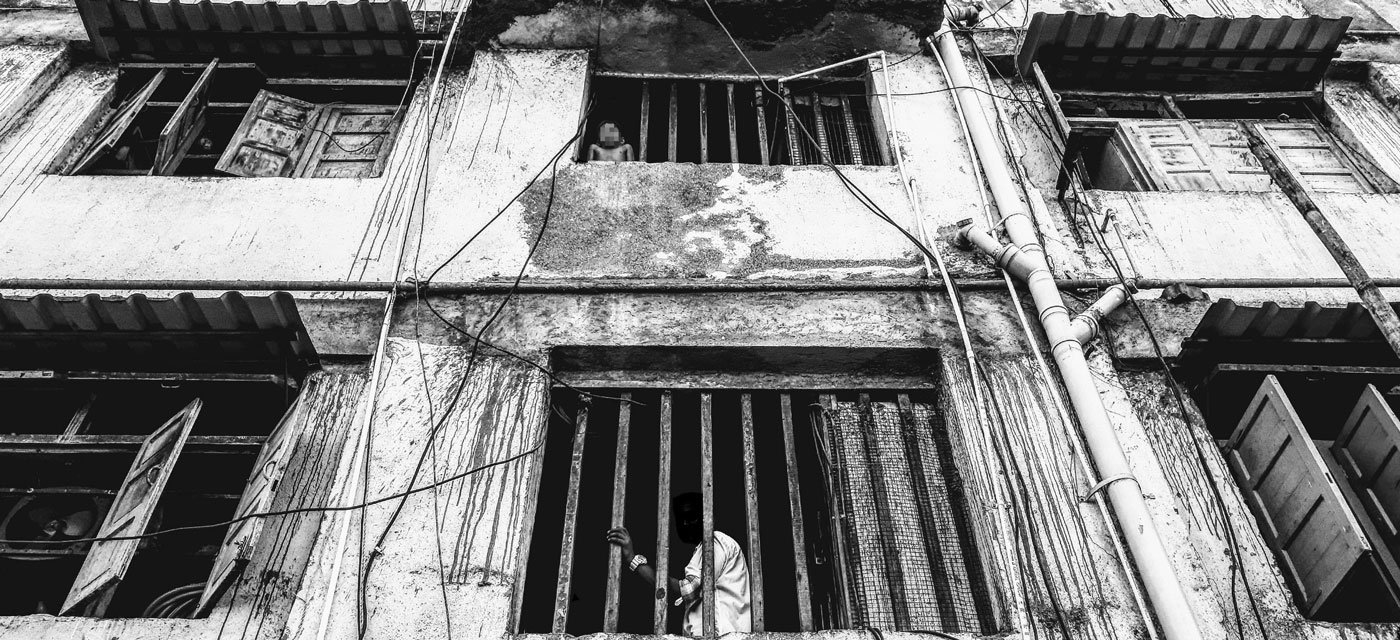

The teenager's immediate world: the streets of the city, and the narrow passageway in the brothel building where he sleeps. In future, Vikram (left, with a friend) hopes to help sex workers who want to leave Kamathipura

Before the lockdown, Vikram was in school from 1 to 6 p.m., and by 7 p.m. he was in a night centre and classes run by an NGO in the area, while the children’s mothers are at work. He would then either return home – sleeping in a passage next to the room where his mother met client – or sometimes stay on in the night shelter.

With the lockdown and his sister too back home, it became even more cramped in their room, which he describes as a “ train ka dabba. ” So he wandered the streets at times at night, or stayed wherever he found work. The family' room is barely 10x10 feet, divided into three rectangular boxes of 4x6, each housing a tenant – an individual sex worker or one with her family. The rooms are also usually the women’s workspaces.

After coming back from Vapi along with Priya and his sister by train on August 14, Vikram was at the neighbourhood naka the next day looking for work. Since then, he has tried selling vegetables, worked at construction sites, carried sacks.

His mother had been waiting to hear from Vikram’s school, and didn’t know when online classes started. He doesn’t have a smartphone and even if he did, his time now is taken up by work, and the family will need money to access the internet for classes. Besides, due to his long absence, the school has taken him off its rolls, says Priya.

She has contacted the Child Welfare Committee in Dongri to help send Vikram to a hostel-school, afraid that he might stop studying if he continues working. The application is in process. Even if it comes through, he will have lost an academic year (2020-21). “I want him to study and not work once school starts. He shouldn’t become a lafantar [vagrant],” says Priya.

Vikram has agreed to attend school again, but wants to continue working too. On the right is his school bag, which he now uses for work

Riddhi got admission in a hostel-school in Dadar, and was taken there in mid-November. Priya resumed sex work after her daughter left, occasionally and when her stomach pain allows her to work.

Vikram wants to try his hand at becoming a chef, he likes to cook. “I have not told anyone, they will say “ Kya ladkiyo ka kaam hai , ” he says. His bigger plan is to move the sex workers who want to move, out of Kamathipura. “I will have to earn a lot so that I can feed them and later find everyone a job they want to really do,” he says. “Many people say they will help the women here, but you see many new didis coming to this area, many subjected to force and bad things [sexual abuse] and thrown here. Who comes of their own will? And who give them protection.”

In October, Vikram went back to the same eatery in Vapi. He worked for two weeks from noon to midnight, cleaning dishes, floors, tables and more. He got two meals a day and tea in the evening. On the ninth day, he had a fight with a co-worker, both of them hit each other. Instead of the agreed-on wage of Rs. 3,000 for two weeks, he received Rs. 2,000 and returned home at the end of October.

He is now delivering parcels from local restaurants around Mumbai Central, using a borrowed bicycle. At times, he also works in a photo studio in Kamathipura, delivering pen drives and SD cards. His earnings remain meagre.

Priya is hoping to hear from a hostel soon, and hoping that her tempestuous and troubled son doesn’t run away from there too. Vikram has agreed to go to school again, but wants to also continue working and helping to support his mother.