It's peak Indian Premier League season, but cricket isn't on people's minds in Nayagaon village. The shadow of the violence in nearby Dhumaspur village still lingers. On the day of Holi on March 21 this year, an altercation between young boys playing cricket had flared into an attack on a Muslim family. The incident was widely reported in the media. The attackers used sticks and rods and reportedly told the family to 'go to Pakistan and play cricket'. Nayagaon is home to three of the five men who allegedly led the violence.

"The police was as inefficient in responding to the attack as it has been in looking into the issues of this area,” says Rakhi Chaudhary, 31, a homemaker. “We have formed a group of 8-10 women who intervene when brawls break out here [usually over incidents of sexual harassment of young girls by village boys]. It's the only way we can protect ourselves. The police are either on traffic duty or busy when politicians visit the area. However, when the rich call them, they respond immediately. We are treated like insects."

Rakhi lives in the Krishna Kunj colony of Nayagaon. (The Maruti Kunj colony is also in this village, which got its name when the late Congress politician Sanjay Gandhi invited the Japanese car-maker to set up shop in the 1970s and workers were given housing here.)

Nayagaon was carved out as a separate panchayat from Bhondsi village of Sohna tehsil in Gurugram district of Haryana in January 2016. The village will go to the polls on May 12 for the Gurugram Lok Sabha constituency.

In 2014, with nearly 13.21 lakh votes cast (of the around 18.46 electors), Rao Inderjit Singh of the Bharatiya Janata Party led the party's first victory in Gurugram. He beat his nearest rival, Zakir Hussain of the Indian National Lok Dal, by a big margin of over 270,000 votes. Rao Dharampal Singh of the Congress, which dominated in Gurugram till 2009, got 133,713 votes or 10.12 per cent of the total. The Aam Aadmi Party’s Yogendra Yadav scored 79,456 or 6.02 per cent of the total votes.

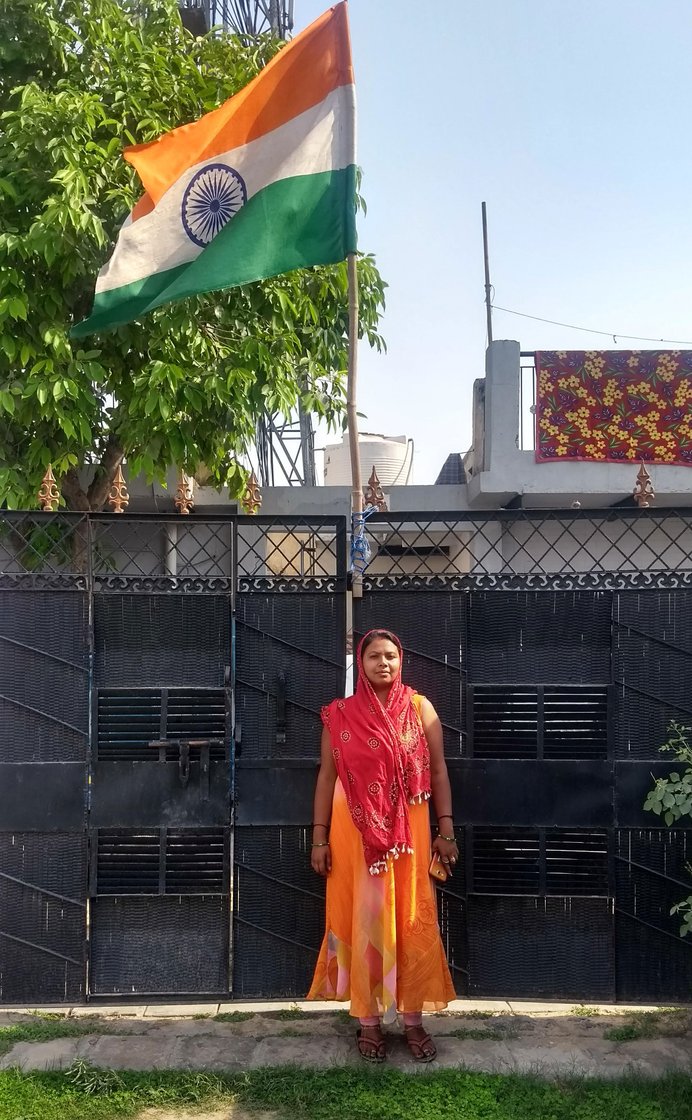

For Rakhi Chaudhary (left) , Rubi Dass and her mother Prabha (centre), and other women here, safety and transport are long-ignored concerns, though Pooja Devi (right) believes a few things have improved

Rao Inderjit Singh is contesting again in the 2019 Lok Sabha election. The other two main candidates are (retired) captain Ajay Singh Yadav of the Congress, and first time entrant to politics Dr. Mehmood Khan of the Jannayak Janta Party-Aam Aadmi Party.

Across both elections, the issues for Rakhi and other women voters here remain the same – and safety is high on their list of concerns. Rubi Dass, a 20-year-old student who lives in Krishna Kunj, says the number of liquor shops near the village has gone up. “There are more alcoholics around us now. Police doesn't respond to complaints. Recently, while a man beat up a woman in a shop where cops were sitting, they didn't bother to intervene. When we commute [by local buses or autorickshaws] to college or school, there are men on bikes lurking around to harass us. The roads are so terrible that you can't even walk away quickly.”

Rao Inderjit Singh of the BJP is contesting again in the 2019 Lok Sabha election. The other two main candidates are Ajay Singh Yadav of the Congress, and first time entrant to politics Mehmood Khan of the Jannayak Janta Party-Aam Aadmi Party

Bhondsi’s sex ratio at 699 is significantly lower than the rest of Haryana’s already low 879 women for every 1,000 men (Census 2011). This is largely a Gujjar belt, and the other main communities here are Rajputs and Yadavs, explains Sunil Jaglan, former

sarpanch

of Bibipur village in Jind

tehsil

of Haryana, around 150 kilometres from Nayagaon (he came up with the ‘selfie with daughter’ campaign in 2015). “While the Yadavs have made progress in the last 7-8 years by encouraging their girls to study, Gujjars haven't,” he says. “Even in Class 8, several Gujjar girls are married. I’ve tried to ensure that girls here have the direct number of the DCP [deputy commissioner of police] on their mobiles in case of any emergency or problem."

Infrastructure is also a major issue here. The exact boundary of the new village is yet to be marked, and even the Rs. 23 crores allocated for infrastructure, says Nayagaon

sarpanch

Surgyan Singh, is yet to come in. The village’s roads are broken and uneven, and there are no real sewerage facilities. Clusters of electricity wires hang over the roofs, causing fights among neighbours.

"Only one out of the six big gullies in my colony has an electricity pole. In the others, the wires criss-cross and people cut them off, leaving dangerously exposed wires hanging. This leads to fights, what can one do?" says 46-year-old Awadesh Kumar Saha. He is originally from Deoria district in Uttar Pradesh, lives alone in Mayur Kunj, and runs a small homeopathy medicines shop in the village from which he earns Rs. 50-100 a day.

“Even though we built our 50- gaj (450-square-foot) house within Rs. 17 lakhs here [compared to much higher rates in Palam Vihar], life was better in Palam Vihar where we rented earlier. It was safer, cleaner... There is no facility for kids here, no parks or hospitals, just one government school till Class 8," says Rakhi, whose husband works at a garment export firm in Manesar.

The inadequate transport facilities allow autorickshaw and school van drivers to charge inflated amounts. “School vans demand more than the normal charge. The auto-driver tells you to pay for an extra passenger if he doesn't get enough people to fill up the vehicle and simply won't go if you don't comply. Many girls drop out of college because there is no conveyance. The closest metro station is Huda [around 13-15 kilometres from Nayagaon and Bhondsi]. A [state transport] bus used to go from here, but now even that has stopped plying,” says Rubi.

Along the road from Delhi, more shiny structures are sprouting in Gurugram, not far from the broken roads, open sewers and dangling wires of Nayagaon

She leaves at 5 a.m. with her father, who works as a gardener in a residential complex, for her 9 a.m. classes, even though the coaching centre is just 45 minutes away from their home. She is preparing for the National Eligibility and Entrance Test (to qualify for medical college). “We have to change different buses and autos to drop me first, and then he goes for work,” she explains. Her mother, Parbha Dass, 38, works in a boutique at an upscale mall 10-15 kilometres away, and earns around Rs.`10,000 a month. It takes her two hours to reach there every morning.

Gurugram is called the 'millennium city' by some; it is among India's top ‘technology hubs’ and the location of several fancy malls, expensive private schools, high-rise residential buildings, vast golf courses and numerous Fortune 500 companies. Along the roughly 45-kilometre drive from central Delhi, even more shiny structures are sprouting, in stark contrast to the broken roads and open sewers of Nayagaon and Bhondsi.

Has anything got better? "Corruption and paying bribes seem to have lessened," says Pooja Devi, 30, a homemaker, whose husband drives an autorickshaw in Gurugram. “Grandparents tell us they are getting their pensions. We all have gas connections. Online payments and transactions including

chalaans

come on our mobiles. Most importantly, Modi has made us feel that

'hum bhi kuch hain

' [we are also someone],” she says.

Sarpanch Surgyan Singh beseeches the group gathered in the blistering May heat to vote for the ruling party. Give them a chance, he says. “We will ask the BJP representative to agree to our demands in writing on a stamp paper, else we'll vote them out in the Assembly election later this year!” says Pooja, a day before the sitting Member of Parliament, Rao Inderjit Singh is due to visit.

“He barely visited for five minutes on Sunday [May 5] and just said we'll do what we can if we win,” Jaglan tells me over the phone the next day. The other two candidates, Ajay Singh Yadav and Mehmood Khan, have yet to set foot in Nayagaon.

Left: 'I’ve tried to ensure that girls here have the number of the DCP in case of any emergency', says Sunil Jaglan. Right: 'Only one out of the six big gullies in my colony has an electricity pole', says Awadesh Saha

“When Rao Inderjit Singh visited the village last Sunday, he asked for votes in Modi's name. Most [BJP] leaders ask for votes in Modi's name," says Awadesh Saha. “In this election, I'd say about 80 per cent of the votes here will go to the BJP, in the name of Modi and the country's security.”

Saha does not think the incident of mob violence on Holi day in Dhumaspur village is a poll issue. “I don't think this will affect voting because the matter quietened down within two weeks. It's been almost two months now...”

Meanwhile, news reports say the family attacked on Holi withdrew its FIR (first information report) in April – three weeks after registering a complaint at the Bhondsi police station. Both sides had apparently reached some sort of understanding.

"The matter has been resolved, people aren't thinking or talking about it anymore, who has the time? Everyone has to get back to their lives and work," Mohammad Dilshad, the main complainant in the attack incident, tells me.

"I am a working person, I don't have a lot of time. If I get the time I'll go and cast my vote,” he adds. “In any case what's the point? Jaatiwad [communalism] is used by politicians on all sides for their own agenda. No party talks about what they'll actually do for you, whether it's building roads, providing jobs, giving proper electricity, etc. It's always the Hindu-Muslim issue. Whether someone is a Hindu or Muslim doesn't matter, the issues of the public must be addressed."