Late one evening in October 2022, a frail, elderly woman rests on a platform in the community centre in Bellary’s Vaddu village, her back leaning against a pillar and her legs stretched out. The 28-kilometre walk along the hilly roads of Sandur taluka has left her exhausted. She has to march another 42 km the next day.

Hanumakka Ranganna, a mine worker from Suseelanagar village in Sandur, is on a two-day

padayatra

organised by the Bellary Zilla Gani Karmikara Sangha (Bellary District Mine Workers Organisation). The protesters are walking 70 kms to submit their demands at the Deputy Commissioner’s office in Bellary (also spelt Ballari), in north Karnataka. This is the sixteenth time in the last 10 years that she has been out on the streets with other mining workers, demanding adequate compensation and an alternate source of livelihood.

She is among the hundreds of women manual labourers in Bellary who were thrown out of work during the late 1990s. “Let us assume that I am 65 years old now. It has been more than 15 years since I lost my work,’’ she says. “Many have died waiting for money [compensation]… even my husband passed away.

“We, the living, are the cursed ones. We don’t know whether these cursed ones will get it [the compensation] or if we will also die without that,” she says. “We have come to protest. Wherever there is a meeting, I participate. We thought we will try this one last time.”

Left: Women mine workers join the 70 kilometre-protest march organised in October 2022 from Sandur to Bellary, demanding compensation and rehabilitation. Right: Nearly 25,000 mine workers were retrenched in 2011 after the Supreme Court ordered a blanket ban on iron ore mining in Bellary

*****

Iron ore mining in Karnataka’s Bellary, Hospet and Sandur regions dates back to the 1800s when the British government mined on a small scale. After Independence, the Government of India and a handful of private mine owners started iron ore production in 1953; the Bellary District Mine Owners’ Association was established with 42 members in the same year. Forty years later, the National Mineral Policy of 1993 introduced sweeping changes to the mining sector, inviting foreign direct investment, encouraging more private players to invest in mining iron ore, and liberalising production Over the next few years there was a spurt in the number of private mining companies in Bellary, along with adoption of large-scale mechanisation. As machines began to take over most of the manual work, women workers, whose job it had been to dig, crush, cut and sieve the ore, were soon made redundant.

Though there is no record of the exact number of women employed as labourers in the mines before these changes took place, it is common knowledge among villagers here that for every two male workers, there were at least four to six women doing manual labour. “The machines came and there wasn’t any job left for us. The machines started doing our work [such as] breaking stones and loading them,” Hanumakka recalls.

“Mine owners told us not to come to the mines anymore. The Lakshmi Narayana Mining Company (LMC) didn’t give us anything,’’ she says. “We worked hard, but we were paid no money. ” The event coincided with another important one in her life: the birth of her fourth child.

In 2003, a few years after she lost her work at the privately-owned LMC, the state government de-reserved 11,620 square kilometres of land – until then marked exclusively for mining by state entities – for private mining. This, combined with an unprecedented surge in demand for ore in China, set off a rapid growth in activity in the sector. By 2010, iron ore export from Bellary had increased by a mind-boggling 585 per cent to 12.57 crore metric tonnes from 2.15 crore metric tonnes in 2006. A report by the Karnataka Lokayukta (a state-level authority that deals with maladministration and corruption) states that by 2011 there were close to 160 mines in the district, employing around 25,000 workers, a majority of whom were men. Unofficial estimates, however, indicate that 1.5-2 lakh workers were attached to allied activities such as sponge iron manufacturing, steel mills, transport and heavy vehicle workshops.

A view of an iron ore mine in Ramgad in Sandur

Despite this boom in production and jobs, a large majority of women workers, including Hanumakka, were never taken back to work in the mines. They did not receive any compensation for being laid off either.

*****

The rapid growth in Bellary’s mining sector came on the back of indiscriminate mining by companies who flouted all rules and reportedly dealt a loss of Rs. 16,085 crore to the state exchequer between 2006 and 2010. The Lokayukta, which was called in to investigate the mining scam, confirmed in its report that several companies were involved in illegal mining; this included Lakshmi Narayana Mining Company, where Hanumakka last worked. Taking cognisance of the Lokayukta report, the Supreme Court, in 2011, ordered a blanket ban on iron ore mining in Bellary.

A year later, though, the Court allowed reopening of a few mines that were found to have not violated any norms. As recommended by an SC-appointed Central Empowered Committee (CEC), the Court placed mining companies in different categories: 'A', for no or least violations; 'B', for few violations; and 'C', for several violations. Mines with the least violations have been allowed to reopen in phases since 2012. The CEC report also laid out the objectives and guidelines for reclamation and rehabilitation (R&R) plans that would need to be prepared for the resumption of a mining lease.

The illegal mining scam toppled the then Bharatiya Janata Party-led government in Karnataka and drew attention to the rampant exploitation of natural resources in Bellary. Nearly 25,000 mine workers were thrown out of work without any compensation. They, however, did not make the headlines.

Left to fend for themselves, the workers formed the Bellary Zilla Gani Karmikara Sangha to press for compensation and re-employment. The union started organising rallies and

dharnas

and even undertook a 23-day hunger strike in 2014 to draw the government’s attention to the plight of the workers.

Left: A large majority of mine workers, who were retrenched, were not re-employed even after the Supreme Court allowed reopening of mines in phases since 2012. Right: Bellary Zilla Gani Karmikara Sangha has been organising several rallies and dharnas to draw the attention of the government towards the plight of workers

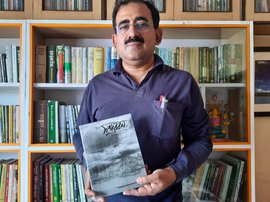

Hanumakka Ranganna, who believes she is 65, i s among the hundreds of women mine manual workers who lost their jobs in the late 1990s

The union is also pushing for the workers’ demands to be included in a key revival initiative called the Comprehensive Environment Plan for Mining Impact Zone. On the direction of the SC, the Karnataka Mining Environment Restoration Corporation was established in 2014 to oversee the implementation of the plan focussed on the health, education, communication and transportation infrastructure in Bellary's mining areas, and to restore the ecology and environment in the region. The workers want their demand for compensation and rehabilitation to feature in this plan. Gopi Y., president of the union, says they have even filed petitions in the Supreme Court and Labour tribunals.

With the workers mobilising in this manner, Hanumakka has found a platform where she feels empowered to raise her voice against the unjust retrenchment of women labourers. She joined 4,000-odd workers [of the 25,000 retrenched in 2011], to file a writ petition in the Supreme Court, demanding compensation and rehabilitation. “Until 1992-1995, we were thumbprints. Back then, there was no one who could be at the forefront to speak [for the workers],” she says about the strength and support she now derives from being a part of the workers’ union. “I haven’t missed a single meeting [of the union]. We have gone to Hospet, Bellary, everywhere. Let the government give what is owed to us,” says Hanumakka.

*****

Hanumakka doesn’t remember when she started working in the mines. She was born into the Valmiki community listed as a Scheduled Tribe in the state. Her home as child was in Suseelanagar, surrounded by hills rich in iron ore deposits. She did what every other landless person from a marginalised community did – she started working in the mines.

“I have worked [in the mines] since I was a child,” she says. “I have worked in several mining companies.” Starting quite young, she became adept at climbing hills, using jumpers to dig holes into the rocks [which contain the ore] and filling them with chemicals for blasting; she was quite deft at handling all the heavy tools required to mine ore. “ Avaaga machinery illa m a [There were no machines back then],” she recalls. “Women would work in pairs. [After the blasting] while one dug out the ore fragments that had come loose, the other sat down breaking them into smaller pieces. We had to break the boulders into three different sizes.” After sieving the ore fragments to remove dust particles, the women would carry the ore on their heads and load them on trucks. “We have all struggled. No one will struggle the way we did,” she adds.

“My husband was an alcoholic; I had to raise five daughters,” she says. “Back then, I earned 50 paise for every tonne [of ore] I broke. We struggled for food. Each person would get half a

rotti

to eat. We would collect greens from the forest, grind them with salt and roll them into small balls to eat with

rotti

. Sometimes we would buy a brinjal, long and round, roast it on firewood, remove its skin, rub salt over it. We would eat that, drink water and go to sleep… that is how we lived.” Working without access to toilets, potable water or protective gear, Hanumakka barely earned enough to eat.

At least 4,000-odd mine workers have filed a writ-petition before the Supreme Court, demanding compensation and rehabilitation

Hanumakka Ranganna (second from left) and Hampakka Bheemappa (third from left) along with other women mine workers all set to continue the protest march, after they had stopped at Vaddu village in Sandur to rest

Hampakka Bheemappa, another mine worker from her village, tells a similar story of hard labour and deprivation. Born into a Scheduled Caste community, she was married off to a landless agricultural labourer as a child. “I don’t remember how old I was when I got married. I started working when I was a child – I hadn’t even attained puberty,’’ she says. “I would earn 75 paise a day for breaking one tonne of ore. We wouldn’t get even seven rupees after working for a week. I would come home crying because they paid me so little.”

After five years of earning 75 paise a day, Hampakka was given a raise of 75 paise. For the next four years, she earned Rs. 1.50 a day, before she was given another raise of 50 paise. “I was earning 2 rupees [a day, for breaking a tonne of ore] for 10 years,” she says. “I would pay 1.50 rupees every week as interest on a loan, and 10 rupees would go to the market… we would buy

nuchu

[broken rice] as it was cheaper.’’

Back then, she thought, the smartest way to earn more was to work harder. She would wake up by 4 a.m., cook and pack food, and be out on the road by 6 a.m. waiting for a truck to ferry her to the mines. Arriving early meant she could break an extra tonne of ore. “There were no buses from our village. We had to pay 10 paise to the [truck] driver; later that went up to 50 paise,” remembers Hampakka.

The ride back home was not easy. Late in the evening, she, along with four or five other workers, would clamber onto one of the trucks loaded with heavy ores. “Sometimes when the truck took a sharp turn, three or four of us would fall on the road. [But] we never felt pain. We would get back again on the same truck,” she recalls. Yet, she never got paid for the labour that went into breaking that additional tonne of iron ore. “If we had broken down three tonnes, we were paid only for two ,” she says. “We could not say or ask anything.”

Mine workers stop for breakfast in Sandur on the second day of the two-day padayatra from Sandur to Bellary

Left: Hanumakka (centre) sharing a light moment with her friends during the protest march. Right: Hampakka (left) along with other women mine workers in Sandur

Quite often, the ore would get stolen and the mestri [head-workman] would penalise the workers by refusing payment. “Three or four times a week we would stay back [to watch over the ore], lighting up a bonfire and sleeping on the ground. We had to do this to safeguard the stones [ore] and get paid.”

Working 16 to 18 hours a day in the mines meant the workers were forced to deny themselves basic self-care. “We bathed once a week, the day we went to the market,” says Hampakka.

At the time of retrenchment in 1998, these women mine workers were earning Rs. 15 a tonne. In a day, they would load five tonnes of ores, which means they took home Rs. 75 a day. When they separated huge fragments of ore, they would earn Rs. 100 a day.

When Hanumakka and Hampakka lost their mining jobs, they turned to farm work to make a living. “We got only coolie work. We would go to remove weeds or stones, harvest corn. We have worked for five rupees a day. Now, they [land owners] give us 200 rupees a day,’’ says Hanumakka, adding, she no longer works regularly in the fields; her daughter now looks after her. Hampakka has also stopped working as an agricultural labourer after her son started taking care of her.

‘’We have shed our blood and sacrificed our youth to [break] those stones [ores]. [But] they [the mining companies] discarded us like peels,” says Hanumakka.