“If everyone grew food on their balconies and terraces, we would have enough food to eat.”

We are in a classroom, invited to sensitise urban students about rural India. The student’s statement drops like a silent bomb. If we let it go, it has the potential to cause irreparable damage – it will stealthily define ‘everyone’ to a class full of entitled young Indians. Instead, we can use it to ignite a discussion on something meaningful. Are there homes without a balcony, terrace or any open area?

PARI Education, the education arm of the People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI), wants to seize these moments to discard stereotypes and widen references. By using PARI stories we want to get students in urban schools and colleges to explore, engage and empathise with rural and marginalised communities. Equally, we want rural students to document and record their communities and participate in building textbooks which include their lives. Maria Montessori held that the ‘reconstruction of society’ will come from the reconstruction of education – where students get to see, hear and learn about the multiple realities in our country.

As teachers we recognise that in the rush to make our students 'global citizens’ they have become alienated from their immediate surroundings and India beyond big cities. By ignoring the many Indias, dismissing their place in the curriculum, we send out the message that they don’t matter. P. Sainath, Founder Editor of PARI says: ‘There is an entire generation growing up in India, foreigners in their own country.’

A student might recognise the image of a woman bending in a field transplanting rice. But can we go beyond the image: Is she a farmer, tenant farmer or agricultural labourer? These farmers also cook, clean, raise children, raise livestock and more. And today, they are protesting against the farm bills

Drawing connections, explaining interlinkages and breaking stereotypes in classrooms and curriculums lie at the heart of PARI Education’s pedagogy. With stories and engagement we want to share that rural India is not a pathetic, poor and singular entity, but in fact a vibrant, interesting and fascinatingly diverse place with many lessons for all of us.

Educationist Kurt Hahn, who defined ‘experiential learning’ said, “There are three ways of trying to win the young. There is persuasion, there is compulsion and there is attraction.” At PARI Education, we want to persuade with logic, compel with conscience and attract with good storytelling.

Discussing multiple realities is particularly important in a country like India where income and social inequalities abound. We have among the highest levels of inequality – the top 10 per cent of Indians have a 55 per cent share of national income.

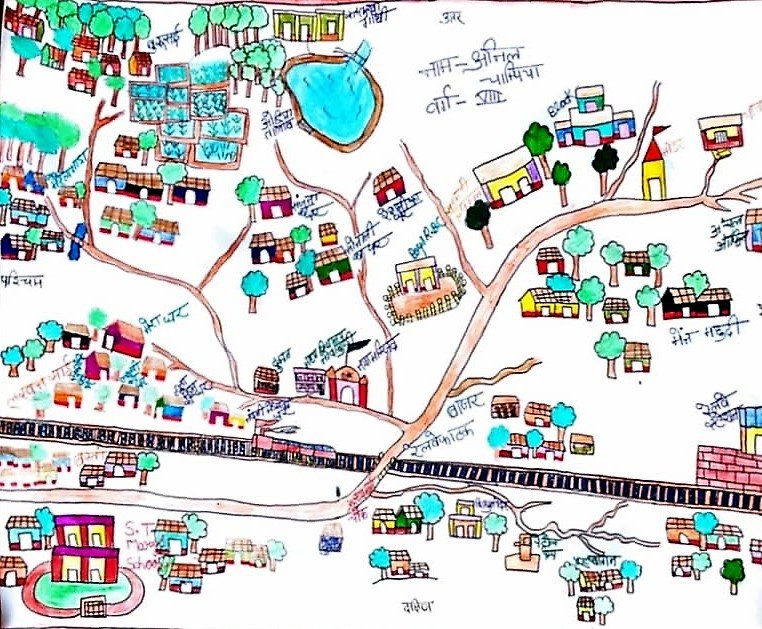

This map was made by Anil Champia, a Class 8 student in Noamundi block of Pashchimi Singhbhum district, Jharkhand. It was part of a project in October 2020 to get students interested in their immediate surroundings by drawing a map of their village

Young urban Indians definitely need a better sense of where they live, who grows their food, where their water and electricity comes from, and who builds the roads and buildings they use every day. They need to see and question why everyone does not share the same access to healthcare, education and livelihood choices that they have. But in order for our young people to start to question, we need to give them the tools of information and empathy, for a start.

A student might recognise the image of a woman bending in a field transplanting rice below the blazing sun. But can we go beyond the image and discuss the processes: Is she a farmer, tenant farmer or agricultural labourer? These farmers also cook, clean, raise children, raise livestock and more. And today, they are protesting against the farm bills, sustaining a movement that impacts our democratic rights.

It’s not as though the curriculum ignores these issues. A quick glance through the syllabi of a national board appears promising with words like ‘poverty’, ‘national income’, ‘labour’ and more. These concepts are explained in textbooks and projects suggested to cement the learning. In practice, it is quite different: exam questions often facilitate ease of marking, and tend to be minimally taxing on the intellect. Take poverty – the Class 11 syllabus suggests that students can ‘prepare a report on poverty alleviation programmes’ as part of their final project. Any enterprising 17-year-old will Google it in a second and list out the various programmes and schemes like Jawahar Rozgar Yojana and Employment Assurance Scheme and so on. But does that qualify as learning about poverty?

Poring over school syllabi, we found opportunities to tweak homework into an interactive project where students could learn, firsthand, about people otherwise invisible to them and be graded. It was important to get into the curriculum as any work outside usually languishes, and is eventually abandoned.

We designed the first PARI school project in a staffroom after interacting with the Economics teachers and finding out what would work for everyone – deepening learning, qualifying marks and ticking the syllabus box. Our first interaction was in August 2018, when a school invited us to speak on different aspects of rural India. My colleague Vishaka George and I found ourselves standing in front of the entire school at 8 a.m. with an iffy projector and dodgy internet connectivity. Beginning with the role of news in a democracy, we moved into the story of Biswas –

a bamboo carrier

in the hills of Agartala, Tripura – a classic teaching story that cuts across subjects and disciplines with Biswas firmly at the centre.

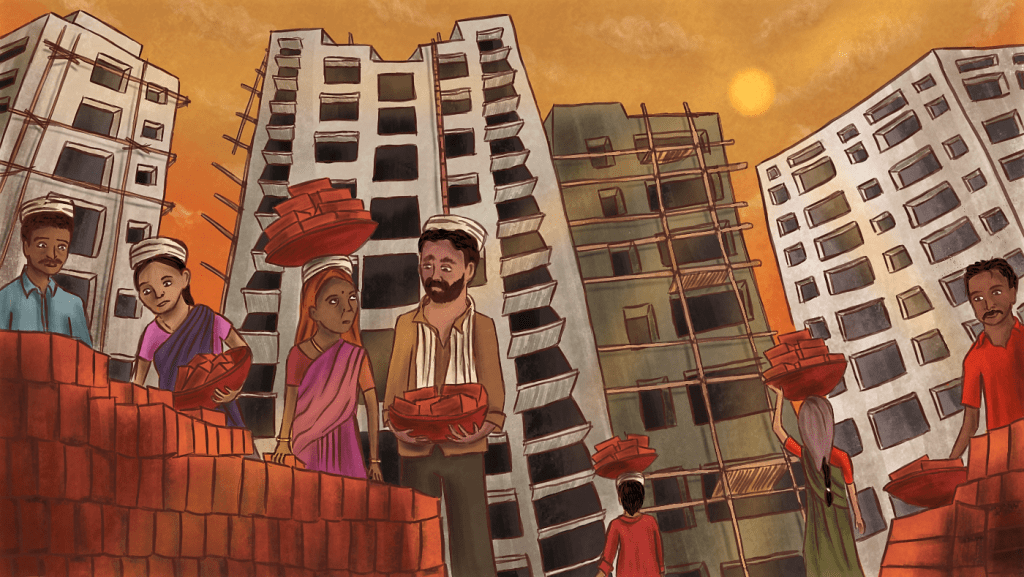

As expected, most students were not aware of migrants or had stereotypical images of them as homeless people, lazy and illiterate, or avaricious and untrustworthy. They were also quite sure that they could write this up in no time ( Illustration: Antara Raman)

Soon we were speaking to universities who were already sending their students to do primary research among marginalised communities. Unwieldy graduate theses were slowly turned into PARI Education stories – merging academic learning with lived experiences of craftspeople, farmers, herders and more. School excursions turned into opportunities to report from the field, document little known occupations and lives.

As PARI journalists who go into classrooms to teach, we can weave our own reporting anecdotes into our teaching, making them more real than just the retelling of others’ stories. We’ve found that this is a more effective method to be able to speak to students as young as 12 years old, as well as to hold the attention of undergraduates and postgraduates over the last almost three years.

A PhD student admitted: “Working on the ground is necessary. My initial drafts were like research articles and I learnt from PARI how to document these as stories and while writing, how to tell your subject's story, not your own views.” You can read these and more in the Editor’s Note at the end of each student piece – an integral part of us documenting these experiences.

“Our students have grown into a better awareness of society,” a school teacher told us after the project finished. “This is the need of the hour.”

The PARI Education team works closely with individual submissions, testing their validity, urging students to move beyond the obvious, and insisting on dignity, safety and respect for subjects. We structure engagements so that students get out there and ask questions and observe. When they write, we show them how to distil their experiences in the vegetable mandi or on a field trip and how to use regional data. They also learn how to use the Census document to not only validate their information but also its importance in a democracy. All this gives a whole new meaning to the ‘localisation’ of education.

The Class 11 syllabus suggests that students can ‘prepare a report on poverty alleviation programmes’. Any enterprising 17-year-old will Google it in a second and list out the various programmes and schemes. But does that qualify as learning about poverty?

One of PARI Education’s first projects was titled ‘The Economics of Migration’. High school students had to record a firsthand account of people around them who had migrated to urban Bengaluru. They were given a ‘cheat sheet’ (available on the website under ‘ Write for PARI ’) with clear guidelines on how to identify a subject, seek consent and more.

As expected, most students were not aware of migrants or had stereotypical images of them as homeless people, lazy and illiterate, or avaricious and untrustworthy. They were also quite sure that they could write this up in no time!

As they began interviewing, many became quite intrigued about the lives of people they knew only as construction labourers, cooks, guards, domestic workers, taxi drivers and so on. The project forced them to engage with people they were used to referring to only by their job specific monikers: ‘guard’, ‘ dhobi ’ or the generic terms ‘ didi ’ and ‘ bhaiya ’.

Finding out their full names and where they came from was simple courtesy, but it also opened the space for conversations to grow. So ‘Ramu’ from Bihar was actually Ramcharan Deo from Baikabishanpur in Bihar, a village with marginal farmers and highly skilled artisans of the centuries-old famous Madhubani art. In their eyes, he was no longer just a cook. They got to learn firsthand about issues such as family debt, child labour, dreams of education, and the loneliness and heartache of years spent away from home not seeing your children grow up or your parents in their old age.

Students got to learn firsthand about issues such as family debt, child labour, dreams of education, and the loneliness and heartache of years spent away from home not seeing your children grow up or your parents in their old age

They realised how little they knew about people who work so closely around them. At 18 years,

Pullina

was barely older than her interviewer – a Class 11 student – in whose house she worked as a domestic worker. Pullina has had to travel multiple times from her home in Assam to Kerala, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu to find jobs in noodle and packaging factories, or anywhere she could get work. An orphan, she is paying for her younger sister’s hospital bills and education.

Listening to these stories changes things, as these 17-year-olds wrote:

-

“Other projects can be done with Google and Wikipedia. But for the PARI Education projects, we had to collect the information ourselves. Interviewing a rural migrant made me aware of the huge social and economic chasm that exists in our country.”

-

“My project showed me how a man can travel thousands of kilometres just to earn that extra 5,000 rupees. It really touched and inspired me.”

-

“...concepts like income disparity, regional imbalance, government reforms, social evils make more sense to me now.”

* * * *

Let us tell you a story. Take you on a journey through rural India. See the different kinds of crops that are grown, and the men and women who grow the food we eat, the buffalo herders who bring us our milk, and the people who live near the rivers and dams that supply us with water and electricity. “I want to explain to my community what their rights are and make them not fear powerful people,” says Jamuna. “I also want to change my community’s dependence on begging and their insistence on early marriage for girls. Begging is not the only occupation to feed oneself; education can also feed you.”

We can show you Sibu Laiya’s rooftop farm that keeps hunger at bay for this landless labourer in Jharkhand. Or take you through the photo story of road worker Pema and her three-year-old son Ngodup, who plays around her as she labours in arduous and hazardous conditions to build the high altitude Leh Padum highway.

'I want to explain to my community what their rights are and make them not fear powerful people', says Jamuna. 'I also want to change my community’s dependence on begging and their insistence on early marriage for girls'

Sometimes we have to start with the teachers.

“Don’t talk too much about caste. Our students are not really aware.”

“But shouldn’t they be made aware of continuing prejudices?”

“Yes, but you know... we don’t want to upset them.”

It’s not easy to get teachers to give away precious ‘lecture’ time and trust you with their classes. And to allay their suspicions about your ‘agenda’. The fact that PARI is a not-for-profit running completely on donations, and the fact that our site is free to use, definitely helps, but we have to get a foot in the door to even share that. Involving teachers and getting them to address in their classes the issues of our times – caste, inequality, injustice – creates a wider arc of influence. They are able to move beyond the textbook and give real life examples.

A teacher wrote to us: “PARI revealed an India and her people that my children and I had, embarrassingly enough, never seen or heard of before. We saw the ink-stained fingers of calligraphers, the warp and weft of the Kuthampally cotton saree; we learned that languages can become extinct too. Or that many freedom fighters don’t feature in history textbooks.

Children read the stories on the migrant crisis during the Lockdown. They were surprised to see how much more there was to the crisis than was shown on TV or in the papers.”

This is what we do – get students to engage, explore and empathise. A young student wrote: “Through PARI we started to acknowledge the life of ordinary people, people around us we tend to ignore. We became more empathetic towards them.”

The PARI Education team consists of Vishaka George (Editor, Social Media), Aditi Chandrashekhar (Senior Content Editor) and Priti David (Education Editor).

This article (with a slightly different title) was first published in The Third Eye ( www.thethirdeyeportal.in ), a feminist think tank working on the intersections of gender, sexuality, technology and education, powered by Nirantar Trust ( www.nirantar.net ).