“Fenk debe, khadaan mein gaad debe [We will throw you, bury you in the sand mine].”

That’s what a mining contractor told Mathuriya Devi, a resident of Khaptiha Kalan village. He was furious with her, she says, and some 20 other farmers who had gathered to protest on June 1 against the killing of the Ken – one of Bundelkhand’s major rivers.

That day, the villagers stood for two hours until around noon, in a jal satyagraha in the Ken. The river originates in Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, and flows 450 kilometres through MP and Uttar Pradesh – merging with the Yamuna in Chilla village of Banda district. Mathuriya Devi’s village – home to around 2,000 people – is in Tindwari block of this district.

But the stretch of the Ken that passes through a small group of villages here has been shrinking – because a band of locals is quarrying its banks on both sides. This mafia functions, the farmers allege, on behalf of two sand mining companies. The quarrying is illegal, says 63-year-old Mathuriya Devi – who holds a little over 1 bigha or roughly half an acre near the Ken – and it is destroying their farms and livelihoods.

“They have been massively digging on our lands – up to 100 feet deep – using bulldozers,” she says. As she spoke to me by the river on June 2, two young men, not known to her, were shooting her on video. “They have already killed our trees, now they’re killing the river which we once used to draw our water from. We even went to the police, but no one listens to us. We feel threatened….”

The resistance to the quarrying has seen an unlikely alliance of Dalits like Mathuriya and small Thakur farmers like Suman Singh Gautam, a 38-year-old widow with two children. The miners have extracted sand from part of the single acre she owns. “They have even fired in the air to intimidate us,” she says.

The farmers of Khaptiha Kalan village mainly grow wheat, gram, mustard and lentils. “My sarson [mustard] crop was standing in the 15 beeswa land I own, but they dug it all this March,” said Suman.

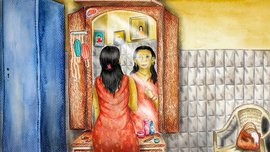

The jal satyagraha on June 1 in the river Ken in Banda district, to protest against sand quarrying in the area that has caused huge losses to the villagers. The women spoke of how the river has shrunk, and during the monsoon, when the piled up quarried mud gets washed away, at times their cattle get trapped in the muddy water and drown.

Over the years, the villagers say, they have learnt to guard their crops. “Sometimes, we have been able to save the crop till harvesting time,” says Mathuriya Devi, “and in unlucky years, we lost the crops to the quarrying.” Arti Singh, another farmer from the village, adds, "We can't only depend on farming on that mining land. We have also been farming on the small plots we own in different locations."

At 76, Seela Devi is the oldest farmer who participated in the jal satyagraha . Her land was once full of babool trees: “We had planted them together, me and my family. Nothing is left now,” she says. “They have dug everything, now they threaten to bury us inside when we speak against them, asking for compensation for our own land.”

Sand quarrying on the banks of the Ken picked up after a massive flood in 1992. “As a result, moorum [the red sand found in the area] got deposited on the banks,” says Ashish Dixit, a rights activist from Banda. The quarrying activities have picked up over the last decade, he adds. “The response to an RTI [right to information application] that I filed says the heavy machines which I have seen being used for years now are prohibited. People here have had raised their voice against this earlier as well.”

"Most sand mining projects are granted based on the district mining plan. The irony is that these plans do not factor in wider catchment areas,” Prof. Venkatesh Dutta of the Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar University, Lucknow, who is an expert on rivers, told me on the phone. “The miners usually resort to channel mining, which devastates the natural design of riverbanks. They also destroy the aquatic habitat. The environmental impact assessments do not look into cumulative impacts of large-scale mining over an extended period. I know of many mining projects in the Yamuna that have changed the course of the river.”

After the jal satyagraha on June 1, the additional district magistrate, Banda, Santosh Kumar and the sub-divisional magistrate Ram Kumar, came to the site. The SDM later told me on the phone, “Those whose lands have been dug up without consent are eligible to get compensation from the government. But if they have sold their lands for money, we will take action against them. An enquiry is in process on this matter.” The compensation is specified under the the Mines and Minerals Act, 1957 (revised in 2009).

“Earlier this year, we had got a complaint of illegal mining on this g ram sabha land against one of the companies which has the land on lease, and they were found guilty,” Ram Kumar adds. “Following this, a report was sent to the DM [district magistrate] and the company has been given a notice. Illegal mining in Banda has been happening for a long time now, I am not denying that.”

Seela Devi, 76, the oldest woman of who participated in the jal satyagraha . Her land was once full of babool trees, she says. “It had many, many trees. We had planted it together; me and my family. Nothing is left now."

Mathuriya Devi came to this village after getting married at the age of nine. “I have lived here since I knew what a village is, what land is. But now, they say, our land and village will submerge in the flood [during the monsoon, because a lot of trees have been flattened by the bulldozers]. Our trees are gone already.”

“This is where we stood for two hours," says Chanda Devi. On June 1, 2020, farmers from Khaptiha Kalan village stood inside the river Ken, leading a jal satyagraha against illegal sand quarrying on the river banks.

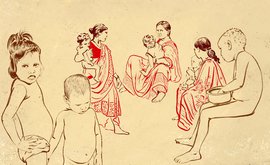

Ramesh Prajapati and his family set out to check his land – it had been dug 80 feet deep for sand mining.

The residents of Khaptiha Kalan were unable to check on their lands during the lockdown. The local young men who operated the bulldozers for the digging told them that their lands have been dug even up to 100 feet deep . A day after the jal satyagraha , some of the women walked across the shallow river to check on their plots.

Trucks line up, waiting to be filled with sand and transport it.

Raju Prasad, a farmer, points to a sand contractor (not in the photo), and says, “He is digging my land. He is not stopping even after I objected. My ladke-bachche [children] are sitting there now. He asks them too to go away. They were cutting even the bamboo, the only trees that remain now. Come with me and see for yourself.”

In response to the jal satyagraha , the quarrying machines were stopped for a while on June 1. The tons of sand already extracted is piled up in huge hillocks.

Mathuriya Devi, Aarti and Mahendra Singh (left to right) stand in front of a board bearing the name of a sand mining agency. They have filed complaints against the agency at the Khaptiha Kalan police chowki .

After Suman Singh Guatam returned to her house from the

jal satyagraha

, she alleges that shots were fired to threaten her. “I informed the police but no one has come yet to even investigate,” she says.

A bullock cart goes past a sand bridge that now barricades the Ken river. The residents of Khaptiha Kalan village say this bridge was made for the purpose of mining.

That's the temporary sand bridge created by the mining agencies to stop the flow of river water – and to help them extract more sand – in the process destroying vegetation, crops, land, water, livelihoods and more.