“I don't know what all of this is about, I think it is something to do with Modi. I come here for the food. We don't have to worry about sleeping hungry anymore,” says 16-year-old Rekha (like most of the people quoted in this story, she prefers to use only her first name). She is a waste worker, who sorts items to recycle from garbage, and lives in Alipur in north Delhi, around 8 kilometres from the Singhu protest site.

She is at the blockade at Singhu, on the Haryana-Delhi border, where farmers have been protesting since November 26 against the three new farm laws passed by the government in September . The protests have drawn tens of thousands of people – farmers, supporters, those just curious, some plain hungry who eat to their heart’s content at the many langars run and managed by the farmers and gurudwaras . The people working at these community kitchens welcome everyone to partake in the meals.

Among them are many families living on nearby pavements and slum colonies, who mainly come to the protest ground for the langar – free meals – served throughout the day, from around 8 a.m. to 9 p.m. Rice, dal , pakodas , laddoos , saag , makki ki roti , water, juice – all are available here. Volunteers are also giving out, for free, a wide range of utility items such as medicines, blankets, soaps, slippers, clothes, and more.

Among the volunteers is Harpreet Singh, a 23-year-old farmer from Ghuman Kalan village in Punjab’s Gurdaspur district, who is also studying for a BSc degree. “We believe that these laws are wrong," he says. "These lands were tilled and owned by our ancestors and now the government is trying to push us out. We do not support these laws. If we don't want to eat the roti, how can someone force us to eat it? These laws have to go.”

“During the lockdown, we didn’t have any food, let alone good food," says 30-year-old Meena (head covered with a green pallu), who lives in Alipur in north Delhi, around 8 kilometres from the Singhu border, sells balloons on the road for a living. "What we eat here is better than anything we have eaten before. The farmers are giving us more than enough to keep us well fed through the day. We have been coming here for a week, twice a day.”

Harpreet Singh (in the blue turban), a 23-year-old farmer from Ghuman Kalan village in Punjab’s Gurdaspur district, who is also studying for a BSc degree, left his home after a call to join the protest. “We are all farmers and believe that these laws are wrong. These lands were tilled and owned by our ancestors for many years and now the government is trying push us out. We do not support these laws. If we don't want to eat the roti, how can someone force us to eat it? These laws have to go,” he insists.

“I serve here with my brothers,” adds Harpreet Singh (not in this photo). “This is our Guru’s langar. It will never finish. It is feeding us and thousands of others. Many people come to help us and contribute for the cause. We are prepared to stay here as long as it takes to remove the laws. We hold langars throughout the day to ensure that everyone who comes here goes back with food in their bellies.”

Rajwant Kaur (with a red dupatta around her and a companion's heads), 50, is a homemaker from Rohini in north-west Delhi. Her son comes here every day to work at the community kitchens, and that’s inspired her to join the movement. “There is nothing else I can do to show my support," she says. "So I decided to accompany my son here to help them cook and feed thousands of people who come here every day. Working here and serving our farmer brothers make me feel good.”

A group of Muslims from Malerkotla, a city in Sangrur district of Punjab, serve zarda , their special rice, and are here from the first day of the protest. Tariq Manzoor Alam of the Muslim Federation of Punjab, Malerkotla, explains that they belong to a region where Muslim and Sikh brothers have stood by each other’s side for centuries. To help the farmers' cause, they brought with them their signature dish. “Till as long as they fight, we will support them," Tariq says, "we are standing right beside them.”

Karanveer Singh is 11 years old. His father sells chowmein from a cart at the Singhu border. “My friends asked me to come here. We wanted to have gajar ka halwa ,” Karanveer says, laughing, while eating zarda, the saffron-coloured rice.

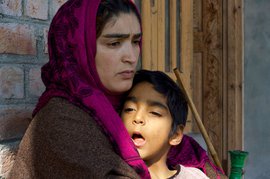

Munni, who is from Kundli village in Sonipat district of Haryana, works at construction sites. She has brought her children to the protest grounds for the food. “I have small kids who wanted to eat something," she says. "I brought them here with me. I don't know what this is about, I think they are fighting about the crops and harvest.”

Besides a place to receive regular meals, the protest site has also become a source of livelihood for many like Pooja, a waste worker, who used to collect trash from various offices. She lives in Sersa block of Kundli, Haryana, and comes to the Singhu protest grounds to collect bottles and boxes, along with her husband. “I sweep the floors and pick up the garbage," she says. "They give me food and milk for my daughter. We come here every day since they set-up camps. We like everything they serve. Sometimes it is bananas and oranges, other times they give soaps and blankets. I sell the bottles and make Rs. 200-300 per day. It helps me pay for my children’s expenses. I hope Waheguru gives them what they want for they have been very kind to us.”

Volunteers from an asram in Karnal, Haryana, prepare hot flavoured milk for the farmers to keep them warm at night. The milk contains dryfruits, ghee, dates, saffron and honey. Fresh milk is procured from the dairies in Karnal every morning.

Volunteers from a welfare society in Kapurthala district of Punjab, preparing hot pakodas as an evening snack. This is usually the most crowded stall at the protest ground.

Akshay is 8 years old and Sahil is 4. “Our parents work at a factory. My mother leaves early in the morning so she can’t make breakfast for us. That is why we come here to eat every day," they says. "I love Sprite," adds Akshay, "and he [Sahil] likes biscuits. ”

Friends Aanchal and Sakshi, 9 and 7 years old (sititng on the ground), say, “Our neighbour told us to go to the border, there is plenty of food there.”

The protest site also provides a medical camp and free medicines to not just the farmers but anyone who visits the stall. Many people living in the adjoining areas are visiting these camps.

Kanchan, 37, from Hardoi district in Uttar Pradesh, said she works at a factory for Rs. 6,500 a month. “I have had fever for a few days. I have already spent so much money on my treatment. Someone at my factory told me that they are giving free medicines at the Singhu border. I came here and got the medicines I wanted. I really want to thank our brothers who are helping everyone in need. They have given us food and medicines that would otherwise cost me hundreds of rupees.”

Sukhpal Singh, 20, Tarn Taran, Punjab, distributing toothpaste, soap, and biscuits. As the roadblock continues at the Delhi-Haryana border, a long line of tractors is not only serving the protesting farmers but also the poor people living in the vicinity, distributing all kinds of items – from sanitary napkins to blankets, food to medicines, even toothbrushes and soap.