When Narayan Gaikwad looks at the handful of castor plants growing in his field, he recalls his Kolhapuri chappals – last used more than 20 years ago. “We used to oil Kolhapuri chappals [slippers] with castor oil. It helped increase its life,” says the 77-year-old farmer, illustrating the close connect between the oil and the footwear famous from the region.

Castor oil has predominantly been extracted in Kolhapur district to grease Kolhapuri chappal s. This footwear, made of buffalo or cow hide, was greased to retain its softness and shape, and the preferred oil for this was from castor plants.

Despite not being native to Kolhapur, castor ( Ricinus communis ) was a popular crop in this region. This thick-stemmed plant with green leaves can be grown all year round. India is the highest castor-producing country globally, with an estimated production of 16.51 lakh tonnes of castor seed in 2020-21. Major castor-producing states in India are Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Odisha and Rajasthan.

“ Majhe vadil 96 varsh jagle [My father lived for 96 years] – and he planted erandi (castor) every year,” says Narayan who continued the tradition and has planted castor in his 3.25 acre farm year after year. He believes his family has been growing castor for over 150 years. “We have preserved these indigenous erandi bean-shaped seeds. They go back at least a century,” adds Narayan, pointing to the seeds he has wrapped safely in newspaper. “ Fakt baiko ani mi shevkin [Only my wife and I are its caretakers now].”

Narayan and his wife Kusum, 66, also manually

extract oil from the castor beans they grow. Despite the proliferation of oil

mills around, they continue with the laborious manual process. “Back in the day, we used to extract oil once every

three months,” says Narayan.

Narayan Gaikwad shows the thorny castor beans from his field

Left: Till the year 2000, Narayan Gaikwad’s field had at least 100 castor oil plants. Today, it’s down to only 15 in the 3.25 acres of land. Right: The Kolhapuri chappal , greased with castor oil, which Narayan used several years back

“When I was a child, almost every household would grow castor and extract the oil. But everyone here has stopped growing castor and started cultivating sugarcane,” says Kusum, who was taught the tricks of castor oil production by her mother-in-law.

Till the year 2000, the Gaikwad family grew more than a hundred castor plants on their land. This number has now decreased to just 15 plants, and they are among the handful of farmers in Kolhapur district’s Jambhali village still growing it. But with the decline in castor bean production in Kolhapur, “now we can hardly extract the oil once every four years,” she adds.

The decline in the demand of Kolhapuri chappals in recent years severely impacted castor oil production in the region. “Kolhapuri chappals are expensive and cost at least Rs. 2,000 now”, Narayan explains. They also weigh almost two kilograms, and have lost their popularity among farmers. Rubber slippers, much cheaper and lighter, are now preferred. And then, “my sons started cultivating sugarcane on a large scale,” says Narayan, explaining the shift away from castor on his land.

When Narayan was 10, he was first taught how to extract castor oil. “Sweep everything and collect them,” he recalls his mother saying as she pointed to over five kilograms of castor beans lying in their farm. The castor plant yields beans within 3-4 months of planting, and the collected beans are dried in the sun for three days.

The process of extracting oil from the dried beans is a laborious one. “We smash the dried beans by treading on them with slippers. This removes the thorny tarfal (hull) and separates the seeds,” Narayan explains. The seeds are then baked on a chuli , a traditional stove made usually of mud.

Once baked, the dried

castor seeds are ready to be crushed for extraction.

Left: A chuli , a stove made usually of mud, is traditionally used for extracting castor oil. Right: In neighbour Vandana Magdum’s house, Kusum and Vandana begin the process of crushing the baked castor seeds

Narayan would help his mother Kasabai crush castor manually on Wednesdays. “We would work in our farm from Sunday to Tuesday and sell the produce [like vegetables and cereal crops] from Thursday to Saturday in the weekly markets nearby,” he recalls. “Wednesdays were the only free day.”

Even today – more than six decades later – the Gaikwads crush only on Wednesdays. This October morning at Kusum’s neighbour and relative, Vandana Magdum’s house, the two work the ukhal-musal to manually crush the seeds.

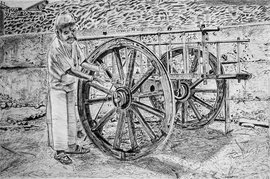

Ukhal – a mortar carved out of black stones – is fitted into the floor of the hall and is 6-8 inches deep. Kusum sits on the floor and helps lift the tall musal made of sagwan wood, while Vandana stands and crushes the castor seeds forcefully with it.

“There were no mixer grinders earlier,” says Kusum, explaining the age-old popularity of the tool.

Thirty minutes into the process, Kusum shows drops of castor oil forming. “ Aata yacha rabda tayar hoto (A rubber-like thing will soon form),” she explains, pointing towards the dark mix smearing her thumb.

After two hours of pounding, Kusum collects the

mix from the

ukhal

in a utensil and

adds boiling water to it. At least five litres of boiling water is required for two kilograms of

crushed castor seeds, she explains. On a

chuli

(stove) outdoors, the mix is further boiled. As Kusum struggles to keep her

eyes open amidst the rising smoke, “We are used to this now,” she says coughing.

Left:

Ukhal

– a mortar carved out of black stone – is fitted into the floor of the hall and is 6-8 inches deep. Right: A

musal

made of sagwan wood is used to crush castor seeds

Kusum points

towards her thumb and shows the castor oil’s drop forming. She stirs the mix of crushed castor seeds and water

As the mix begins to simmer, Kusum pulls a thread from my shirt and adds it in. “ Kon bahercha aala tar tyacha chinduk gheun takaycha, nahi tar te tel gheun jaate [If an outsider comes to your house during this process, we pull off a thread from their cloth. Otherwise, they steal the oil],” she explains. “It’s a superstition," Narayan is quick to add, "In the old days, it was believed that any outsider would steal the oil. That is why they put this thread.”

Kusum stirs the concoction of water and crushed castor seeds with a daav (a large wooden spoon). After two hours, the oil separates and begins to float to the top.

“We never sold the oil and always gave it for free,” says Narayan, recalling how people from villages neighbouring Jambhali would come to his family for castor oil. “For the past four years, no one has come to take the oil,” Kusum says as she filters the oil out with a sodhna (strainer).

To this day, the Gaikwads have never considered selling castor oil for a profit.

The yields from producing castor are anyway negligible. “The vyaparis (traders) from Jaysingpur town nearby buy castor beans for as low as Rs. 20-25 per kilogram,” says Kusum. In industries, castor oil is used in coatings, lubricants, waxes and paints. It’s even used in soaps and cosmetics.

“Now people don’t have the time to extract oil

manually. When required, they buy readymade castor oil directly from the

market,” says Kusum.

Left: Crushed castor seeds and water simmers. Right: Narayan Gaikwad, who has been extracting castor oil since the mid-1950s, inspects the extraction process

After stirring the castor seeds and water mixture for two hours, Narayan and Kusum separate the oil floating on top from the sediments

Even in these times, the Gaikwads are keen to preserve castor’s time-tested benefits. “ Dokyavar erandi thevlyavar, doka shaant rahte [If you keep a castor leaf on your head, it helps you remain calm],” says Narayan. “Consuming a drop of erandi oil before breakfast kills all the jantu [bacteria] in the stomach.”

“A castor plant is a farmer’s umbrella,” he adds, pointing towards the tapering ends of its glossy leaves which help repel water. This is especially useful during the long rainy season between April and September. “Crushed castor seeds are also great organic fertilisers,” Narayan says.

Despite its many traditional uses, castor plants are fast disappearing from Kolhapur’s farms.

The growing demand of sugarcane crops in

Kolhapur has worsened

erandi’

s waning

popularity. Data from the Gazetteers Department, Government of Maharashtra,

show that sugarcane was cultivated on

48,361 acres

of land in Kolhapur during 1955-56. Land under

sugarcane cultivation crossed

4.3 lakh acres

in 2022-23.

Kusum filters the castor oil using a tea strainer. 'For the past four years, no one has come to take the oil,' she says

' A castor plant is a farmer’s umbrella,' says Narayan (right) as he points towards the tapering ends of the leaves that help repel water during the rainy season

“Even my children have not even learned how to grow and extract castor oil,” Narayan says. “They don’t have the time.” His sons, Maruti, 49, and Bhagat Singh, 47, are farmers and grow several crops, including sugarcane. His daughter, Minatai, 48, is a homemaker.

When asked about the difficulties in extracting castor oil manually, Narayan replies, “There’s no problem. It’s a good exercise for us.”

“I love preserving plants, so I plant castor every year,” he states with conviction. The Gaikwads make no monetary profit from the labour they put into growing castor. Yet, they intend to carry their tradition forward.

In the midst of 10-foot-tall sugarcane, Narayan and Kusum have held on to their castor plants.

This story is part of a series on rural artisans by Sanket Jain, and is supported by the Mrinalini Mukherjee Foundation.