“Ghulam Nabi, your eyes will deteriorate. What are you doing? Go to sleep!”

That’s what my mother used to say when she found me carving wood late into the night. I rarely stopped even after her scolding! I have practised my craft for over 60 years to reach where I am today. My name is Ghulam Nabi Dar and I am a wood-carver from Srinagar city, Kashmir.

I don’t know when I was born but I am in my 70s, and have lived in this city’s Malik Sahib Safakadal locality my whole life. I studied at a nearby private school and dropped out in Class three because of my family’s financial situation. My father, Ali Muhammad Dar, used to work in the neighbouring Anantnag district but he returned to Srinagar when I was 10.

He started selling vegetables and tobacco in the city to support us – his family of my mother, Azzi, and 12 children. As the eldest, I helped my father and so did my brother Bashir Ahamad Dar. When there wasn’t much work, we used to wander around and my

mamu

[maternal uncle] once complained about this to my father. It was my

mamu

who suggested we do wood-carving work.

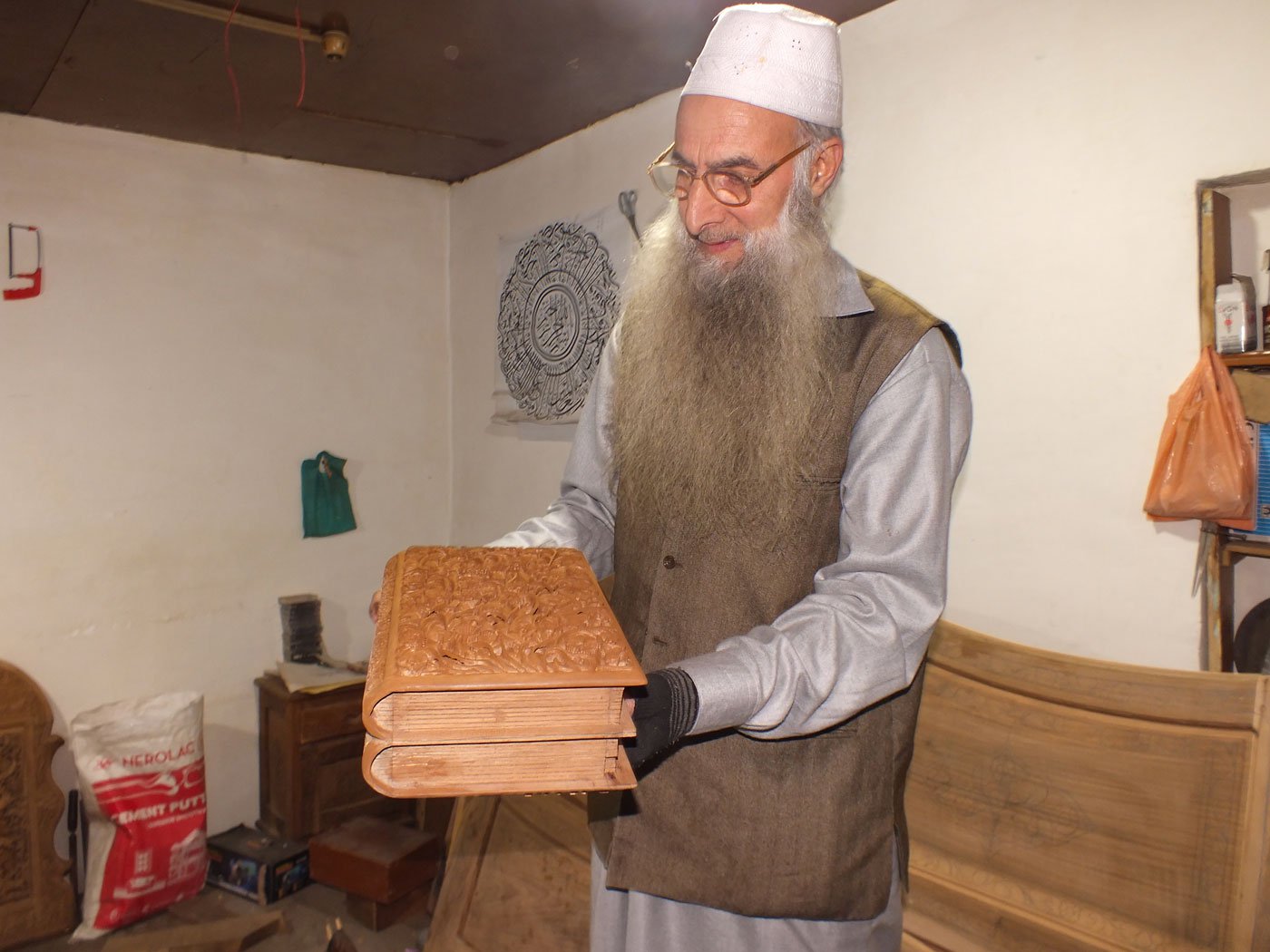

Ghulam Nabi Dar carves a jewelry box (right) in his workshop at home

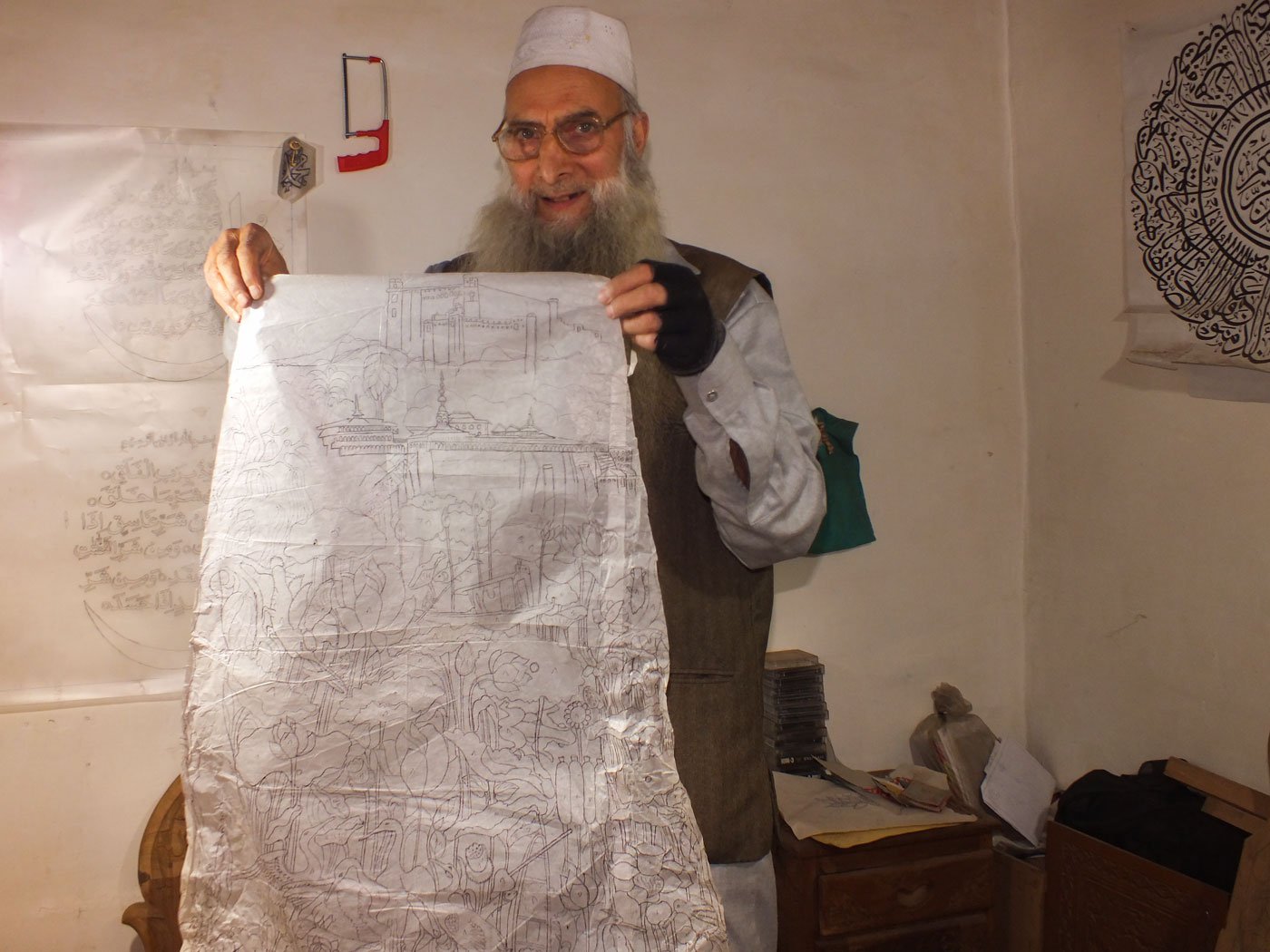

He draws his designs on butter paper before carving them on the wood. These papers are safely stored for future use

So we brothers began working for different artisans, carving polished walnut wood. Our first employer paid us both roughly two and a half rupees each. And that was only after we had worked for two years with him.

Our second teacher was our neighbour, Abdul Aziz Bhat. He used to work for a big handicraft company in Kashmir that had international customers. Our workshop in Srinagar’s Rainawari locality was filled with many other skilled craftspersons. Bashir and I worked here for five years and every day our work began at 7 a.m. and would go on till after sunset. We would carve wooden jewellery boxes, coffee tables, lamps and more. I would return home and practise on little pieces of wood.

There was a room in the factory where finished work was kept, and it was always locked up, out of sight. One day, I snuck in. When I saw all the designs of trees, birds and many more creations shining in every corner of this room, it was paradise for my eyes. I made it my life’s mission to master this art and thereafter would often sneak in to observe different designs and then try them out. I got caught looking by another worker who accused me of stealing. But later he saw my dedication to the craft and let me go.

No one ever taught me the things that I learnt through observation in that room.

Left: Ghulam carves wooden jewellery boxes, coffee tables, lamps and more. This piece will be fixed onto a door. Right: Ghulam has drawn the design and carved it. Now he will polish the surface to bring out a smooth final look

Ghulam says his designs are inspired by Kashmir's flora, fauna and landscape. On the right, he shows his drawing of the Hari Parbat Fort, built in the 18th century, and Makhdoom Sahib shrine on the west of Dal Lake in Srinagar city

Earlier, people carved designs of chinar tree [ Platanus orientalis ], grapes, kaindpoosh [rose], panpoosh [lotus] and more. People have forgotten kaindpoosh designs and now prefer easy carving. I’ve tried my best to bring back some old designs and create at least 12 original designs; two got sold. One of them was a duck carved on a table and the second was a creeper plant design.

In 1984, I submitted two designs for a state award given by the Directorate of Handicrafts, Jammu and Kashmir. I won for both my submissions. One of these designs was based on a panchayat meeting, from a scene out of a village in Kashmir. In this design, people from different communities, Sikhs, Muslims, Pandits are seated around a table, along with children and hens. There is

samavar

[utensil] filled with

chai

, cups for it, a hookah and tobacco on the table. Around the table there were children and hens.

After winning, I felt motivated to submit my work for the national award in 1995. This time I carved on a box. Each corner had a different facial expression and emotion: joy shone through laughter, crying shown with tears, anger and fear. In between these figures, I made 3D flowers. I won this award on my first try too. The president of India, Shankar Dayal Sharma, presented this award to me on behalf of the Development Commissioner (Handicrafts) and Development Commissioner (Handlooms), Ministry of Textiles, Government of India. It recognised my efforts towards, “keeping alive the ancient traditions of Indian handicrafts.”

After this, people who used to give 1,000 rupees for a piece of work started to give me 10,000 rupees. Mehbooba, my first wife passed away around this time, and my parents insisted I marry again since we had three young children. My son and daughter studied till Class 12 and my youngest daughter till Class 5. Abid, the oldest, is 34 now and works with me. He won the state award on his first try in 2012.

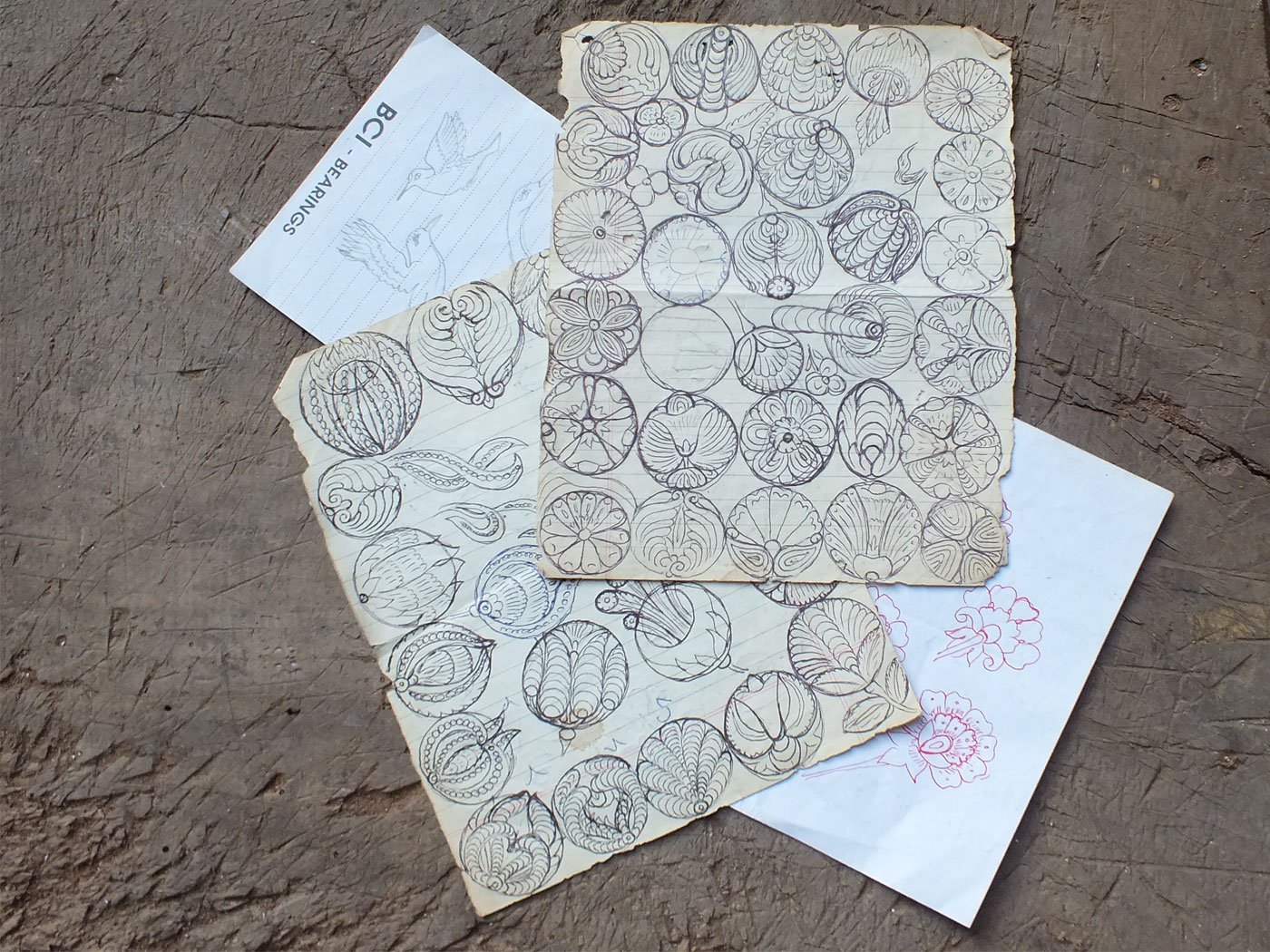

'Over the years, some important teachers changed my life. Noor Din Bhat

was one of them,' says Ghulam. He has carefully preserved his teacher's

40-year-old

designs

Left: Ghulam's son Abid won the State Award, given by the Directorate of Handicrafts, Jammu and Kashmir, in 2012. Right: Ghulam with some of his awards

Over the years, some important teachers changed my life. Noor Din Bhat was one of them, famously known in Narwara [locality] of Srinagar as Noor-ror-Toik. He was one of my favourites.

I met him when he was bed-ridden and paralyzed on the right side of his body. I was in my 40s at the time. People used to bring him planks of wood from factories or a coffee table, and he used to carve them from his bed. He supported his wife and son with this income and taught this craft to few young people like my brother and me. When I asked him if he would teach us, he jokingly said, “You’re a little late.”

My teacher taught me how to use the tools, sandpaper and create designs. Before he passed away, he instructed me to go to a garden to observe flowers if I ever felt frustrated or stuck: “See the curve and lines in Allah’s creations and learn.” He inspired me to teach this craft to others and take it forward.

Earlier, my hand used to move a lot faster; I could work like a machine. Now I have become old and my hands are not as fast. But I am always thankful.