Violence against women in India

FOCUS

A PARI Library bulletin on how abuse and harassment of women, often with brutal force, limits their mobility and compromises their safety

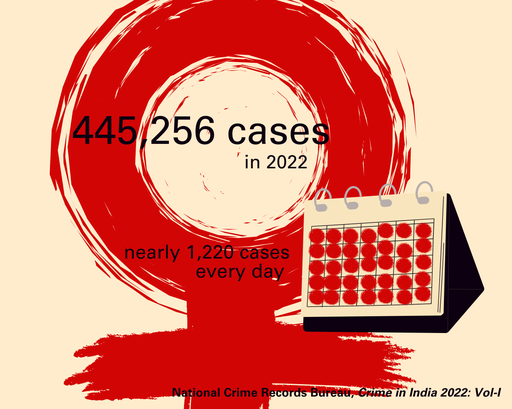

Precisely 4,45,256 cases were registered in the year 2022 as ‘crime against women’ in India. This amounts to nearly 1,220 cases everyday – those reported officially and gathered by the National Crime Records Bureau, that is. The actual incidence of such gendered violence is bound to be greater than the official numbers.

Violence against women has insidiously permeated into every aspect of daily living. Workplace harassment, trafficking of women, sexual abuse, domestic violence, sexism in art and language – all hinder the safety and security of women.

It's a well-documented fact that women hesitate to report cases of crimes committed against them, further marginalising their voices. Take for instance the case of Barkha, a 22-year-old Dalit woman from Uttar Pradesh. Barkha states that the police refused to lodge an FIR for her complaint of rape and kidnapping when she first approached them because the main accused was a local political leader. Another rape survivor, Malini, who is a resident of Haryana, says, “the police asked me to take some money from the accused and to just let it [the crime] go. When I refused to compromise, they scolded me and said, "We will put you in lock-up if you don’t compromise”.”

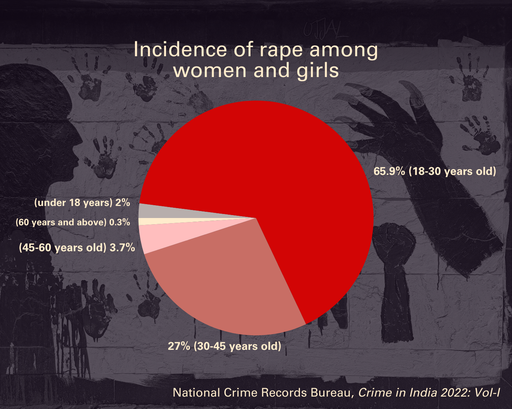

Police negligence, informal khap panchayats and lack of access to medical and legal resources work in tandem, discouraging women from seeking reparations for violence against them. A 2020 report, Barriers in Accessing Justice: The experiences of 14 rape survivors in Uttar Pradesh, India shows that in six of the reviewed cases, police registered an FIR (first information report) only after complaints were escalated to senior police officers. In the remaining five cases where an FIR was filed, it was done only after a court order. Markers like caste, class, disability and age augment one’s exclusion from state mechanisms which are in place to redress gender-based violence. As per a report by Dalit Human Rights Defenders Network, perpetrators targeted girls younger than 18 years of age in 62 per cent of the 50 case studies of sexual violence against Dalit women. The Crime in India 2022 report also notes that the the incidence of rape cases in highest among women aged between 18 to 30 years.

Girls and women with psychological or physical disabilities are more prone to sexual violence in India, this report notes, due to the barriers in communication as well as their dependency on caretakers. Even when complaints are registered, like in the case of 21-year-old Kajri who is living with psychiatric disability, the legal process itself becomes the punishment. Kajri was kidnapped in 2010 and spent 10 years as a victim of trafficking, sexual assault, and child labour. Her father says, “it’s been difficult to continue my job in one place because I need days off to take Kajri to give police statements, tests etc. I get fired when I ask for frequent leave.”

In the essay Conceptualising Brahmanical Patriarchy in Early India, Prof. Uma Chakravarty writes of the enduring “obsession with creating an effective system of control and the need to guard them [women] constantly.” This control, as the essay notes, is often undertaken by rewarding women who subscribe to patriarchal norms and shaming those who do not. Regulatory norms which violently limit women’s mobility are often rooted in the fear of women's sexuality and financial independence. “Earlier they [her in-laws] would say that I was going to meet with other men whenever I would go to see any pregnant woman in the village or take them to the hospital. Being an ASHA, this is my duty,” says 30-year-old Girija. A resident of Uttar Pradesh’s Mahoba district, Girija faces pressure from her in-laws to quit her job as an Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA). “Yesterday my husband’s grandfather hit me with a lathi [stick] and even tried to throttle me,” she adds.

When women do manage to work and get paid for it, workplace harassment is the next gendered hurdle. As per a survey of garment sector workers in National Capital Region and Bengaluru, 17 per cent of women workers reported instances of sexual harassment at the workplace. “Male managers, supervisors and mechanics – they would try to touch us and we had no one to complain to,” notes Latha, a factory worker in the garment industry (read: When Dalit women united in Dindigul). Aiming to strengthen the collective bargaining power of female workers, the Vishaka Guidelines (1997) recommends organisations to form a Complaints Committee which should be headed by a woman and have as women not less than half of its members. Despite the existence of such directives on paper, their implementation continues to be feeble. Violence against women pervades at work and home.

In the 2019-21 National Family Health Survey (NFHS), 29 per cent of women aged 18-49 years reported having experienced physical violence at home since the age of 15. Six per cent reported experiencing sexual violence. However, only 14 per cent of the women who had ever experienced sexual or physical violence sought help to stop it – from family, friends, or government institutions. There is a growing number of cases of violence women suffer from partners. “Meri gharwali hai, tum kyon beech mein aa rahe ho [She is my wife. Why are you interfering]?,” Ravi would say when someone objected to his beating his wife. In just the year 2021, about 45,000 girls were killed by their partners or other family members around the world.

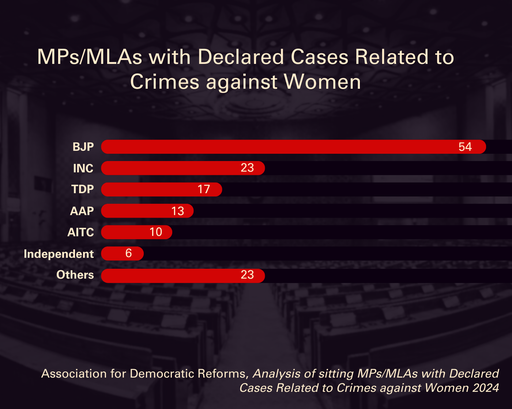

Without doubt, the endorsement of violence in romantic relationships portrayed in popular culture is a factor. In Impact of Indian Cinema on Young Viewers, depictions of “chedh khaani” or eve teasing (better termed as street sexual harassment) is seen as harmless banter by 60 per cent of the youth. The sinister normalisation of gendered violence is noted in another recent publication, Analysis of sitting MPs/MLAs with Declared Cases Related to Crimes against Women 2024, which states that as high as 151 sitting MPs/MLAs have cases of crimes against women declared in their candidature affidavits.

Add to this alarming mix the culture of victim-shaming, especially towards those who have experienced sexual violence: Radha, who was raped by four men from her village in Beed district, was then accused of being “characterless” and defaming her village when she spoke out against them.

The list of such crimes is long, and their patriarchal roots are deeply enmeshed in our society. Read more about violence against women in PARI Library's section on Gender-based violence here.

Cover design: Swadesha Sharma

AUTHOR

PARI Library

COPYRIGHT

PARI Library

PUBLICATION DATE

15 அக், 2024