Polamarasetty Padmaja’s family gave 25 tulam (250 grams) of gold jewellery as dowry when they got her married in 2007. “When my husband finished spending it all, he was done with me too,” says 31-year-old Padmaja, who repairs watches for a living.

Padmaja’s husband sold the jewellery, piece by piece, and spent it on alcohol. “I had to provide for myself and my family, especially my children,” she says. She started repairing watches – and is perhaps the only woman doing this work in Visakhapatnam city of Andhra Pradesh – after her husband left the family in 2018.

Since then, she has been working at a small watch shop at a monthly salary of Rs. 6,000. But when the Covid-19 lockdown began in March, her earnings took a hit. She received only half her salary that month, and nothing at all in April and May.

“I somehow managed to pay the rent from my savings until May,” says Padmaja, who lives in the city’s Kancharapalem locality with her sons Aman, 13, and Rajesh, 10. “I hope that I will be able to keep sending my children to school. I wish for them to study more than I did [till Class 10].”

Padmaja’s income supports the entire household, which includes her parents. Her unemployed husband doesn’t give any financial support. “He comes even now, but only when he doesn’t have money,” says Padmaja. She lets him stay when he visits.

“The decision to learn to repair watches came up unexpectedly," she recalls. “When my husband left, I was lost. I was meek and had very few friends. I didn’t know what to do until one of my friends suggested this.” Her friend’s brother, M. D. Mustafa, taught Padmaja the repair work. He owns a watch shop in Visakhapatnam’s busy Jagadamba Junction area, where the shop that Padmaja works is also located. Within six months, she had picked up the skill.

Polamarasetty Padmaja’s is perhaps the only woman doing this work in Visakhapatnam; her friend’s brother, M. D. Mustafa (right), taught her this work

Before the lockdown, Padmaja repaired about a dozen watches in a day. “I never thought I would be a watch mechanic, but I enjoy it,” she says. With the lockdown, there weren’t many watches to fix. “I missed the clicks, the tick-tocks, and the sound of fixing a broken watch,” she says while replacing the broken ‘crystal’ ( transparent cover) of a customer’s watch.

Managing with barely any income has been a struggle. Even though Padmaja resumed work in June, after the lockdown began easing, she has been receiving only Rs. 3,000 – half her salary – every month. For two weeks in July, the watch shops in Jagadamba Junction remained shut because the area was a containment zone. Business hasn’t picked up yet, she says. “I work from 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. every day. I can’t try my hand at any other job.”

Opposite the shop where she works is Mustafa’s kiosk, on the pavement. A few watches for children and adults, both digital and analog, are displayed on a shelf in the blue-coloured stall. He stocks spare parts and instruments like tweezers, and the eye loupe he uses, below the shelf.

After reopening the kiosk in June, Mustafa’s income fell from Rs. 700-1,000 a day to about Rs. 50. So when he had to shut his shop in July because of the containment, he let it stay that way. "There was no business and my travel expenses were more than my income," he says. And he needs Rs. 40,000-50,000 every six months to replenish stocks. So he has been living off his savings since July.

Mustafa has worked on watches for nearly half a century. “I learned the craft from my grandfather and father, from when I was 10 years old,” says the 59-year-old, who has a BCom degree. They were both horologists (makers and repairers of watches and clocks) who owned shops in Kancharapalem. Mustafa set up his own shop in 1992.

M.D. Mustafa, who has been using up his savings since July, says, ''When mobile phones were introduced, watches began losing their value and so did we''

“Our profession was respected in the past. We were known as watch-makers. When mobile phones were introduced, watches began losing their value and so did we,” he says. Until 2003, he was even a member of the Visakha Watch Makers Association. “It was like a union, with around 60 senior watch mechanics. We met every month. Those were good times,” he recalls. The group disbanded in 2003, and many of his associates have either quit the business or left the city. But Mustafa still carries his membership card in his wallet. “It gives me a sense of identity,” he says.

At a shop not far from Mustafa’s kiosk, Mohammad Tajuddin speaks of the changes too: “This job is fading away due to advancing technology. Maybe no one will be left to repair watches one day.” Tajuddin, now 49, has been repairing watches for 20 years.

Originally from Eluru city in West Godavari district of AP, Tajuddin shifted to Visakhapatnam with his wife and son four years ago. “Our son got full scholarship to study civil engineering at a technology institute here,” he says.

“The lockdown gave me time to explore different kinds of watches, but it took away my salary,” he adds. He received only half of his monthly salary of Rs. 12,000 from March to May. The next two months went by without a salary.

Tajuddin used to work on about 20 watches a day, but he had hardly any to repair during the lockdown. He fixed a few watches from home. “I mostly repaired batteries, replaced the glass [‘crystal’] or strap for cheap, unbranded watches,” he says. In August, though, he received his full pay.

Watch-repairing is not the tradition of any specific community, and receives no support from any quarter, says Tajuddin. Watch-repairers must receive government aid, he adds.

Mohammad Tajuddin (top row) used to work on about 20 watches a day, but he had hardly any to repair during the lockdown. S.K. Eliyaseen (bottom right) says, 'Perhaps some financial support would do, especially in these hard times'

“Perhaps some financial support would do, especially in these hard times,” agrees S.K. Eliyaseen, a watch-repairer at a popular store in Jagadamba Junction. He too was not paid his salary of Rs. 15,000 from April to June, and received only half in March, July and August. “My children’s school kept calling and asking us to pay fees and buy new books,” says the 40-year-old father of two kids, aged 10 and 9. “We were running the house on my wife’s earnings.” His wife Abida, a primary school teacher, earns Rs. 7,000 a month, and they borrowed Rs. 18,000 from her parents for the fees and books.

Eliyaseen was 25 when he started working in this field . “Repairing watches was my wife’s family business. It interested me so much that I made my father-in-law teach me after we got married,” he says. “This skill has given me the strength and means to survive,” adds Eliyaseen, who grew up in Visakhapatnam and didn’t go to school.

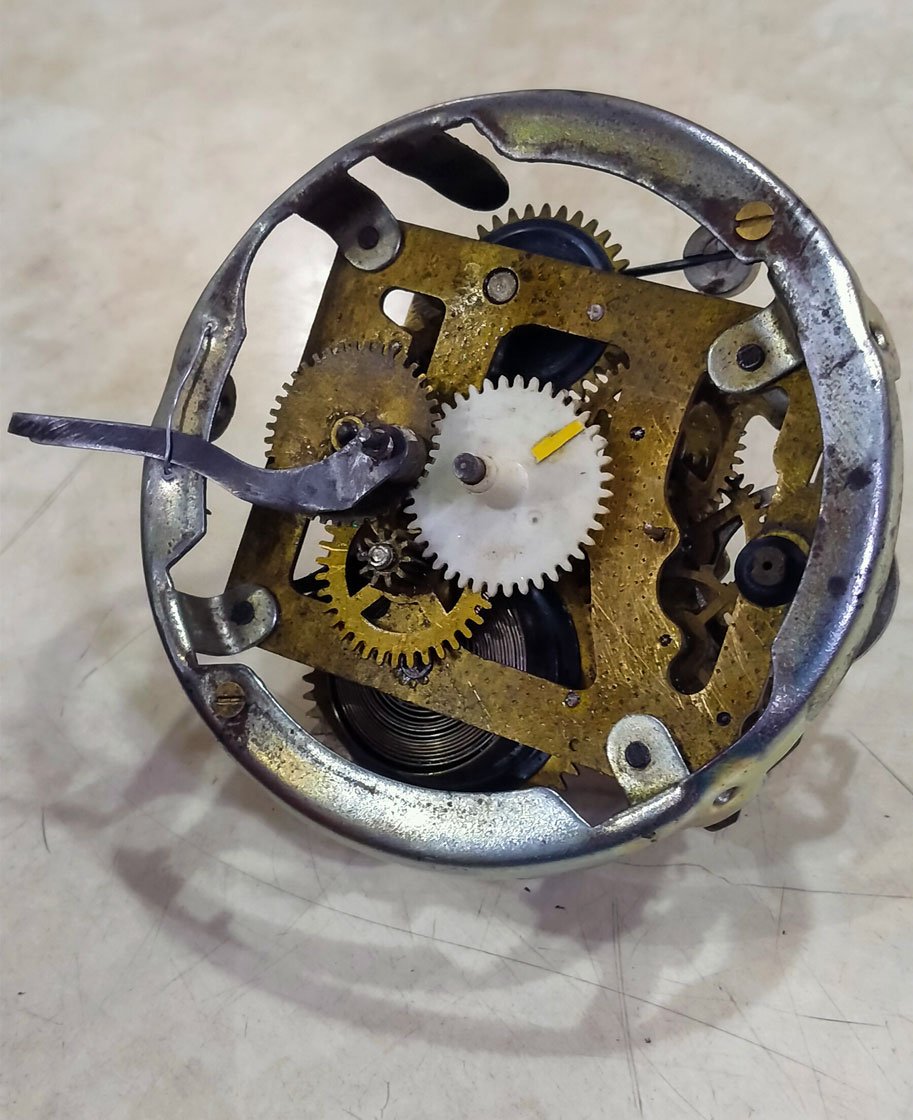

While he can’t afford to own the expensive watches he works on, Eliyaseen is content with handling them. But the big watch brands usually ignore repairing, he adds, and don’t employ anyone for the task. The ‘movement’ (the watch’s internal mechanism) is often just replaced with a new one instead of correcting the fault. “We watch-mechanics can repair the movement,” he says. “We can repair something that is unnecessarily replaced by the top watch brands of the world. I am proud of my work.”

Though their own skills too are highly fine-tuned, Eliyaseen, Mustafa and other watch mechanics of Jagadamba Junction revere 68-year-old Mohammed Habibur Rehman. He can repair any kind of watch, they say, including vintage timepieces such as pendulum clocks. He also handles the complex mechanisms of older clocks in an instant, and specialises in diving and quartz watches. “Only a few are left who truly appreciate a pendulum clock,” says Habibur ( in the cover photo on top ). “Nowadays it’s all digital.”

'Even before the coronavirus, I had very few watches to repair. Now it's one or two a week', says Habibur, who specialises in vintage timepieces (left)

The owner of the shop where Habibur works had asked him to stay at home because of the coronavirus. “I come anyway. I have watches to repair,” he says. He has received a salary of only Rs. 4,500 a month for the past 5-6 years, down from Rs. 8,000-12,000 until 2014, when a new owner who took over the shop didn’t think there would be much demand for his expertise in vintage watches.

“Even before the coronavirus, I had very few watches to repair. I used to repair 40 a month maybe. Now it's one or two a week,” says Habibur. He didn’t get his salary in April and May, but has been paid in full since June. "If they cut my salary, it would be hard to survive.” Habibur and his wife, 55-year-old Zulekha Begum, manage their home expenses with their combined incomes. Before the lockdown, she earned around Rs. 4,000-5,000 a month by stitching clothes.

Habibur came to Visakhaptnam looking for work when he was 15. Back home, in Parlakhemundi town of Odisha’s Gajapati district, his father was a watch-maker. When he was in his 20s, there were about 250-300 watch mechanics in Visakhapatnam, he recalls. “But now there are hardly 50,” he says. “Maybe after the pandemic ends, there’ll be none left.”

He has passed on his skills to the youngest of his four daughters; the other three are married. “She likes it,” he says of the 19-year-old who is studying for a BCom degree. “ I hope she goes on to become one of the best watch-mechanics of all time.”

Habibur has another dream: he wants to establish his own brand of watches. “To repair a watch is almost like mending time itself,” says Habibur. ““I don’t care about my age. When I work with a watch, it doesn’t matter how much time goes by. I work on it as long it takes. I begin to feel 20.”