The only thing that mattered to Bharti Kaste, 23, was her family. She dropped out of school after Class 10 and took up a job so that her younger sisters could continue their education. She worked as a helper at a company, labouring relentlessly to ensure her father and elder brother who were also working, could breathe a bit easy. All she cared about or thought of was her family. That was until May 2021.

After that there was no family to think about.

On May 13, 2021, five of Bharti’s family members went missing overnight in their village, Nemawar in Madhya Pradesh’s Dewas district. It included her sisters, Rupali, 17, and Divya, 12, her mother Mamata, 45, and her cousins, Pooja, 16, and Pavan, 14. “I couldn’t get in touch with any of them,” she says. “We panicked when they didn’t return home after a day.”

Bharti filed a missing complaint with the police, who then began investigating the disappearance.

One day turned into two, and two days turned into three. The family members didn’t return. With each passing day, the fear about their absence grew stronger. The knot in Bharti’s stomach tightened. The silence in her home grew louder.

Her worst fears deepened.

Five of Bharti's family went missing on the night of May 13, 2021 from their village, Nemawar in Madhya Pradesh’s Dewas district

On 29 June 2021, a full 49 days after the five went missing, the police search brought the tragic news. Five bodies were exhumed from a farmland belonging to Surendra Chauhan, an influential member of the dominant Rajput community in the village. Chauhan is associated with right-wing Hindu outfits and said to be close to Ashish Sharma, the BJP MLA from their constituency.

“Even though we expected it deep down in our hearts, it still came as a shock,” says Bharti, whose family belongs to the Gond tribe. “I can’t describe what it's like to lose five members of the family in one night. We were all hoping for a miracle.”

In one night in Nemawar, a tribal family lost five members.

The police arrested Surendra and six other accomplices for the massacre.

*****

The population of tribals in MP stands at around 21 per cent and includes Gond, Bhil and Sahariya tribals among others. Despite their significant number, they are not safe: the state records the most atrocities against the Scheduled Tribes – between 2019-2021, says Crime in India 2021 published by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB).

In 2019, the state recorded 1,922 atrocities against STs, which rose to 2,627 two years later. This is a 36 per cent increase and more than double the national average of 16 per cent.

In 2021, India recorded 8,802 crimes against STs – Madhya Pradesh made up 30 per cent of those with 2,627 atrocities. That is seven a day. While the more gruesome ones make the national headlines, intimidation and subjugation in their daily lives goes unreported.

'I can’t describe what it's like to lose five members of the family in one night,' says Bharti from a park in Indore

Madhuri Krishnaswamy, leader of Jagrit Adivasi Dalit Sangathan (JADS), says the sheer volume of crimes against the tribal communities in Madhya Pradesh makes it difficult for an activist to keep track of them. “The important thing is that some of the most chilling cases have come in the political fiefdoms of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party leaders,” she adds.

In July this year, an unsettling video from the state’s Sidhi district had gone viral: a drunk man, Parvesh Shukla, was seen urinating on a tribal man. Shukla, a BJP worker, was arrested soon after the video surfaced on social media.

However, the law doesn’t act as swiftly when there is no video to garner public outrage. “The Adivasi communities are often displaced or moving from one district to another,” she says. “That makes them vulnerable. Further, the laws allow powerful and dominant communities to dehumanize and assault them.”

The massacre of Bharti’s family in Nemawar by Surendra was allegedly over his affair with her sister, Rupali.

The two were seeing each other for quite some time but their relationship came to an abrupt end when Surendra announced his engagement to another woman. It caught Rupali by surprise. “He had promised her they would get married after she turned 18,” Bharti says. “But in reality, he just wanted to have a physical relationship. He used her and then decided to marry somebody else.”

A furious Rupali threatened to expose Surendra on social media. He summoned her to his farmland one evening, offering to amicably resolve the matter. Pavan accompanied Rupali but was stopped at a distance by Surendra’s friend. Rupali met Surendra where he was waiting in a deserted patch of the farm with an iron rod. As soon as she arrived, he smacked her on the head and killed her on the spot.

Surendra then sent a message to Pavan that Rupali had tried to kill herself and she needed to be taken to the hospital. He told Pavan to get Rupali’s mother and sister who were there at the house. In truth, Surendra wanted to kill all the people in the family that knew Rupali had been summoned by him. One by one, Surendra killed them all, and buried them on his land. “Is this a reason to kill an entire family?” asks Bharti.

From 2019 to 2021, there was a 36 per cent increase in atrocities against STs in Madhya Pradesh

When the bodies were exhumed, Rupali and Pooja’s bodies didn’t have clothes on them. “We suspect he raped them before the murder,” says Bharti. “It destroyed our lives.”

According to the latest NCRB data , Madhya Pradesh has witnessed 376 incidents of rape in 2021 – more than one per day – with 154 of them being minors.

“We didn’t exactly live a rich life before but we still had each other,” says Bharti. “We worked hard for each other.”

*****

Tribal atrocities by dominant communities occur for a variety of reasons. One of the most common excuses to attack tribal communities is a land conflict. When tribals are given state land it reduces their dependence on landlords for a livelihood, thereby threatening their hegemonic dominance in the village.

In 2002, when Digvijay Singh was the Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh, nearly 3.5 lakh landless Dalits and Adivasis were promised land titles in order to empower them. Over the years, some of them even received the necessary paperwork. But possession remains with the dominant caste landlords in a majority of the cases.

When the marginalised communities have asserted their rights, they have paid for it with their lives.

In late June 2022, the administration reached Rampyari Sehariya’s Dhanoriya village in Guna district to mark the land that belonged to her. When the administration finally drew up the boundary for her, it was the day she had been dreaming of and the culmination of a two-decade long struggle for land ownership for the Sahariya Adivasi family.

But two families from the dominant Dhakad and Brahmin communities were in possession of that land.

Jamnalal's family belongs to the Sahariya Adivasi tribe. He is seen here chopping soyabean in Dhanoriya

On July 2, 2022, as Rampyari walked towards her 3-acre land to inspect it, she was beaming with pride, she was a landowner now. But when she reached her farmland, members of the two dominant families were operating a tractor on it. Rampyari intervened and asked them to vacate the land, which led to an argument. She was beaten up at the end of it, and set on fire.

“When we heard what happened, her husband, Arjun ran to the farmland and found his wife in a burnt state,” says Jamnalal, 70, Arjun’s uncle. “We immediately took her to the district hospital in Guna, from where she was referred to Bhopal because her condition was critical.”

Six days later, she succumbed to her burns. She was just 46 years old. She is survived by her husband and four kids, all of whom are married.

The family, which belongs to the Sahariya tribe, earned its livelihood through labour work. “We had no other source of income,” says Jamnalal, while chopping soyabean in a farmland in Dhanoriya. “When we finally got hold of the land, we thought we could at least cultivate food for self-consumption.”

Ever since the incident, Rampyari’s family has left their village of Dhanoriya in fear. Jamnalal, who is still in the village, doesn’t reveal where they stay. “We were all born in the village, we grew up here,” he says. “But only I will die here. I don’t think Arjun and his father will return.”

Five people have been arrested and charged with Rampyari’s murder. The police stepped in and arrested the culprits with alacrity.

![Jamnalal continues to live and work there but Rampyari's family has left Dhanoriya. 'I don’t think Arjun [her husband] and his father will return,' he says](/media/images/06a-IMG20230930112937-PMN-Living_in_fear-t.max-1400x1120.jpg)

![Jamnalal continues to live and work there but Rampyari's family has left Dhanoriya. 'I don’t think Arjun [her husband] and his father will return,' he says](/media/images/06b-bIMG20230930113251-PMN-Living_in_fear-.max-1400x1120.jpg)

Jamnalal continues to live and work there but Rampyari's family has left Dhanoriya. 'I don’t think Arjun [her husband] and his father will return,' he says

*****

When people commit atrocities, the victims go to the state machinery for justice. But in the case of Chain Singh, it was the state machinery that killed him.

In August 2022, Chain Singh and his brother Mahendra Singh were returning on a bike from a forest near their village of Raipura in Madhya Pradesh’s Vidisha district. “We needed some wood for the house work,” says Mahendra, 20. “My brother was riding the bike. I sat at the back, balancing the wood we had managed to collect.”

Raipura nestles close to the densely forested areas of Vidisha, which means the area is pitch dark after sunset. There are no street lights. The brothers could only rely on the headlight of their bike to navigate the uneven terrain.

After carefully crossing the bumpy roads through the forested area, Chain Singh and Mahendra, who belong to the Bhil tribe, reached the main road only to find two jeeps full of forest guards right in front of them. The headlight of the bike directly pointed at the jeeps.

“My brother stopped the bike immediately,” says Mahendra. “But one of the forest guards shot at us. There was no aggression from our end. We were merely carrying wood.”

Chain Singh, 30, died on the spot. He lost control of the bike and collapsed. Mahendra, at the back, was hit too. The wood they had collected fell off his hands and he fell on the ground along with the bike before passing out. “I felt like I would die too,” says Mahendra. “I thought I was floating in heaven.” The next thing he remembers is waking up at the hospital.

Mahendra's (in the photo) brother Chain Singh was shot dead by a forest guard near their village Raipura of Vidisha district

Omkar Maskole, the district forest officer of Vidisha, said the judicial enquiry is going on regarding the incident. “The accused was suspended but he is now back in service,” he said. “Once the judicial enquiry submits its report, we will take the appropriate action accordingly.”

Mahendra is skeptical that the forest ranger who shot his brother will be charged. “I hope there are some consequences for what he did,” he says. “Otherwise what message are you sending? That it is simply okay to kill a tribal man. Are our lives so dispensable?”

The incident has upended the family of Chain Singh, who was one of only two earning members of the household. The other is Mahendra who still walks with a limp even over a year on. “My brother is gone and I can’t work much as a labourer because of the injury,” he says. “Who will look after his four small kids? We have an acre of farmland, where we cultivate chana for self-consumption. But there has been almost zero cash flow for a year.”*****

Bharti has not been able to earn any money either since the incident.

Ever since her family was massacred in Nemawar, she left the village with her father, Mohanlal and elder brother, Santosh. “We didn’t have any farmland over there,” says Bharti. “We just had our family. When there was no family, we didn’t see any point in living there. It brings back memories, and it didn’t feel very safe either.”

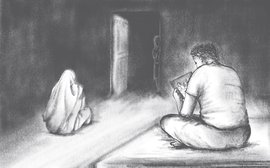

Bharti's father and brother wanted to let go of the case and start afresh. 'Maybe they are scared. But I want to ensure the people who killed my family get punishment. How can I start afresh when there is no closure?' she says

Since then Bharti has had a fallout with Mohanlal and Santosh. They don’t live together anymore. “I live with my relatives here in Indore, and they live in Pithampur” she says. “My father and brother wanted to let go of the case and start afresh. Maybe they are scared. But I want to ensure the people who killed my family get punishment. How can I start afresh when there is no closure?”

Rupali wanted to be a doctor. Pavan aspired to be in the army. Bharti, who has even begged in the streets to ensure her siblings get food on the table, can’t think of anything else but justice.

In January 2022, she carried out a ‘Nyay yatra’ from Nemawar to Bhopal on foot. The 150 kilometer journey, which spanned a week, was supported by the opposition Congress party. Mohanlal and Santosh didn’t take any part in it. “They don't speak to me much,” she laments. “They don’t even ask how I am doing.”

The government of Madhya Pradesh announced Rs. 41 lakh to the family for the lost lives. The amount was divided in three – Bharti, Mohanlal and Santosh, and her uncle’s family. She is currently surviving on that. She lost her job because she couldn’t focus at all. She wants to return to school and complete her education that she had left midway to look after her family. But only after she sees the case through.

Bharti is afraid that the case against Surendra might be diluted because of his political connections. She is meeting with credible and affordable lawyers to make sure that doesn’t happen. In the past two years, almost everything in Bharti’s life has changed except one: she is still thinking about her family.