“Hume pata hi nahi humaara beta ekdam kaise mara, company ne hume bataya bhi nahi [We don’t exactly know how our son died. The company didn’t even tell us this],” says Neelam Yadav.

The 33-year-old is standing inside their house in the town of Rai in Sonipat, avoiding all eye contact as she speaks. Around six months ago, Ram Kamal, her brother-in-law’s son, whom she has raised since her marriage in 2007, died while at work in a local food retail factory where the 27-year-old worked in the AC repair unit.

It was June 29, 2023 and Neelam remembers it as a slow and sunny day. Her three young children – two girls and a boy, and her father-in-law, Shobhnath had just finished lunch that she had cooked, the regular meal of daal bhaat (lentil soup and rice) . She was cleaning the kitchen while Shobhnath lay down planning to take a short afternoon nap.

Around 1 p.m. the doorbell rang. She washed her hands and while fixing her dupatta, went to see who it was . Two men in blue uniforms stood at the door, playing with their bike keys. She recognised them as from the company where Ram Kamal worked. Neelam remembers one of them speaking and informing her, “Ram has got an electric shock. Come to the Civil Hospital quickly.”

“I

kept asking how he was, if he was alright, in his senses. They just said he

wasn’t,” Neelam says, her voice breaking .She and Shobhnath did not waste time looking for public transport, and instead requested the men to immediately take

them to the hospital on their bikes. It took them around 20 minutes to reach

the hospital.

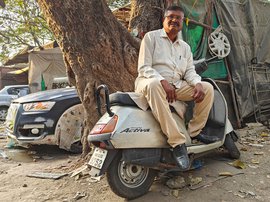

Left: Six months ago, 27-year-old Ram Kamal lost his life at work in a food retail factory. He worked as a technician in an AC repair unit. Right: Ram's uncle Motilal standing outside their house in Sonipat, Haryana

Left: The cupboard dedicated for the safekeeping of Ram Kamal’s documents and evidence of the case. Right: Ram lived with his uncle and aunt at their house in Sonipat since 2003

Motilal, Neelam's husband and Ram's uncle, was at work when he received the call from his wife. He works at a construction site in Samchana, Rohtak and arrived at the hospital on his scooter, covering the distance of 20 kilometres in about half an hour.

“They

had kept him in the postmortem unit,” his 75-year-old grandfather, Shobhnath says. His aunt, Neelam

remembers wanting to cry: “I was not able to look at him. They had covered him

with a black cloth. I kept calling for him,” she says.

*****

The now deceased young man had been sent by his parents, Gulab and Sheila Yadav, to live with his aunt and uncle. He was only seven years old and Motilal had fetched him from their home in Nizamabad tehsil in Azamgarh district of Uttar Pradesh. “We have raised him,” Motilal said.

Ram Kamal had been working at the factory since January 2023 and earned Rs. 22,000 per month. He sent half the salary back home to his family of four – his mother, father, wife and eight-month-old daughter.

“His

little daughter was his support system, now what will happen to her? The

company people didn’t ask about her once,” says Shobhnath. The company’s owner is yet to visit the family.

!['If this tragedy took place at their home [the employers], what would they have done?' asks Shobhnath, Ram's grandfather.](/media/images/04a-5-NA.max-1400x1120.jpg)

'If this tragedy took place at their home [the employers], what would they have done?' asks Shobhnath, Ram's grandfather. Right: It was two co-workers who informed Neelam about Ram's status

Ram did not come home the night before his death, Neelam recalls: “He said he was too busy with work. Ram had been on the work site for about 24 hours at a stretch.” The family did not know much about his work hours. Some days, he had to skip meals. On other days, he slept in the company’s shack at the factory. “Our son was very hard-working,” Motilal smiles. In his free time, Ram was fond of video-calling his daughter, Kavya.

From some of the other employees at the factory, the family came to know that Ram had been repairing a cooling pipeline – a task for which he had not been provided with any safety equipment or precautions. “When he went to the area with his AC-pipe spray and plier, he was not wearing slippers and his hands were wet. If the company manager had cautioned him, we wouldn’t have lost our son today,” says his uncle, Motilal.

A day after learning about the loss, Ram's father Gulab Yadav came to Sonipat for the last rites of his son. Days later, he visited the Rai Police Station in Haryana, to lodge a complaint against the company for negligence. Sumit Kumar, the Investigating Officer assigned to the case, tried to persuade Ram’s family to settle, says the family.

“The

police asked us to settle for one lakh [rupees]. But nothing will happen. Now,

only a court case will do,” Motilal says.

The police at the station in Rai, Sonipat, asked Ram's family to settle

Incidents of factory workers’ deaths are not uncommon in Sonipat which has emerged as an industrial hub over the past couple of decades. Most of the workers here are migrants from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Delhi

Feeling that the police were brushing him off, Motilal decided to file a court case a month after the incident had taken place. The lawyer representing Ram in Rai’s labour court, Sandeep Dahiya, charges Rs. 10,000 for paperwork alone. For the family, with a monthly income of around Rs. 35,000, it is a high sum to pay. “We don’t have any other option, but I have no idea how many rounds we’ll be required to undertake in courts,” Motilal, who is now the single-earning member of the family, says.

The police officer also could not help Gulab and Motilal recover Ram’s scooty bike that he used to travel to the factory, located about 10 kms from their house. Before visiting the company to ask for the bike, Motilal had called the police station. An officer told him to speak directly with the supervisor on site. However, the supervisor, dismissed Motilal’s request: “When I went to recover the bike the supervisor asked why we didn’t settle? Why had we filed a case.”

Motilal also does not know where Ram's worker ID card is. “The FIR calls him a contractual worker. But his salary was sent through the main company. He was assigned an employee ID, but they haven’t given it to us yet.” He also adds that the company has not provided any CCTV footage.

The supervisor claims that, “it was the boy’s

negligence. He had already serviced an AC… His hands and legs were wet, which

led to the electric shock.” He dismisses any lack of responsibility on his part.

Left: Ram Kamal’s postmortem report states the entry wound was found on his left finger, but the family are skeptical about the findings. Right: Article about Ram's death in Amar Ujala newpaper

The postmortem report states that Kamal’s “electric entry wound is present over the dorsolateral aspect of the left little finger.” However, the family does not believe this to be true, especially since Ram was right-handed. Neelam says, “After an electric shock, people have burn marks, their face becomes black. His was absolutely clear.”

Incidents of factory workers’ deaths are not uncommon in Sonipat which has emerged as an industrial hub over the past couple of decades. Most of the workers here are migrants from Uttar Pradesh, followed by Bihar and Delhi (Census 2011). The police says they see at least five cases of workers injured in nearby factories every month. “In various cases, when the employee gets injured, the case does not reach the police station. Compromise is made already,” he says.

With Ram’s case now in court, Dahiya says there is scope for appropriate negotiation. “So many people die, who asks after them? This is a case of IPC 304 and I will fight for the little girl's future,” he said. Section 304 of the Indian Penal Code deals with cases of “culpable homicide not amounting to murder.”

Despite financial and emotional roadblocks, Ram’s family is also adamant. Shobhnath says, “If this tragedy took place at their home [the employers], what would they have done? We are doing the same,” and adds, “ jo gaya vo toh vaapis na aayega. Par paisa chaahe kam de, hume nyaay milna chahiye [The one we have lost will never return. Even if they don’t give enough compensation, justice is what we want].”