Everyday lives of queer people in rural India

FOCUS

In this bulletin, PARI Library spotlights the voices and data around the queer community who live away from big metros and cities, and face social exclusion in their personal and professional lives

Confinement, forced marriage, sexual and physical violence and ‘corrective’ therapies are the kind of threats and experiences members of the LGBTQIA+ community often face, as this 2019 report, Living with Dignity, published by the International Commission of Jurists, says.

Take the case of Vidhhi and Aarush (names changed) who had to leave their respective homes in Thane and Palghar districts in Maharashtra, to live together in Mumbai. Vidhhi and Aarush (who identifies as a trans man) moved into a rented room in the city. “The landlord is not aware of our relationship. We must hide it. We don’t want to vacate the room,” Aarush says.

LGBTQIA+ persons are often denied housing, forcefully evicted, and harassed by family, landlords, neighbours and the police. Many face homelessness, says the Living with Dignity report.

Stigma and harassment force many transgender people, especially in rural India, to leave home and find a safer space. A study of transgender persons in West Bengal released by the National Human Rights Commission in 2021 found that “the family pressurises them to mask their gender expression.” And nearly half of the people left their households because of the discriminatory behaviour of their family, friends and society.

“Just because we are transgender, does it mean we don’t have izzat [honour]?” asks Sheetal, a trans woman, speaking from years of bitter experience – in school, at work, on the streets, almost everywhere. “Why does everyone treat us with contempt?” she asks in this story titled, ‘ People stare at us as if we are evil spirits ’.

In Kolhapur , Sakina (her assumed name as a woman) tried to tell her family about her desire to be a woman. But they insisted that she (who they saw as male) marry a girl. “At home I have to live as a father, as a husband. I cannot fulfil my wish to live as a woman. I live a dual life – as a woman in my mind and as a man in the world.”

Prejudicial attitudes towards people belonging to the LGBTQIA+ community prevail in many parts of our country. The transgender community, for instance, is deprived of many of the rights available to cisgender people in the spheres of education, employment, healthcare, voting, family and marriage, shows this study on the human rights of transgender as third gender.

In Himachal Pradesh’s Dharmshala town, the first Pride march held in April 2023 was met with suspicion by some locals like Navneet Kothiwala. “I don’t think this is right, they [queer people] shouldn’t fight for this because what they are asking for is not natural – how will they have children?”

Transgender persons are regularly subjected to discrimination and isolation, and denied access to accommodation as well as jobs. “We do not like to beg, but people don’t give us work,” says Radhika Gosavi who realised that she was a transgender around the age of 13. “Shopkeepers often tell us to get lost. We bear everything so we can earn enough to eat,” she adds.

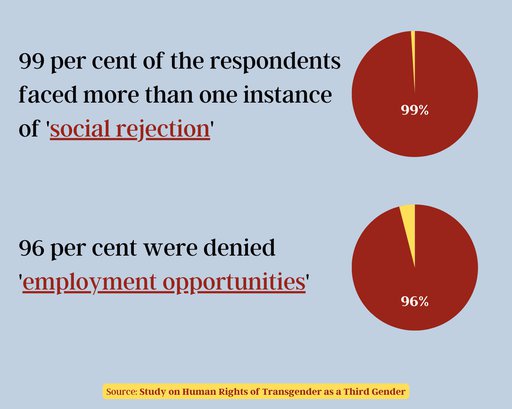

Social rejection and denial of rightful job opportunities is a real problem for transgender people. A Study on Human Rights of Transgender as a Third Gender (conducted in Uttar Pradesh and Delhi) showed that 99 per cent of the respondents reported encountering more than one instance of ‘social rejection’ and around 96 per cent had been denied ‘employment opportunities’.

“If we have to go anywhere, the rickshaw driver will often not take us and people treat us like untouchables in trains and buses. No one will stand or sit next to us but they will stare at us as if we are some evil spirits,” says transgender person, Radhika.

LGBTQIA+ persons face discrimination while accessing public spaces – including shopping malls and restaurants. They are denied entry, refused to provide services, subjected to invasive surveillance and discriminatory pricing. Completing education becomes an added challenge. K. Swesthika and I. Shalin, kummi (traditional song) dancer-performers from Madurai, had to discontinue their studies for BA and Class 11 respectively due to the harassment they faced for being trans women. Read: Trans artists in Madurai: bullied, isolated, broke

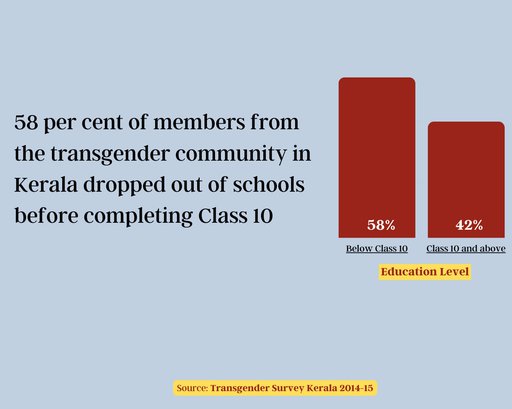

This survey, published in 2015 (a year after the Supreme Court passed a judgement recognising transgender as a third gender) shows that 58 per cent of members from the transgender community in Kerala dropped out of schools before completing Class 10. The reasons for discontinuing education include severe harassment at school, lack of reservation and unsupportive home environment.

*****

“‘In the women’s team, there is a man playing’ – these were the sorts of headlines,” remembers Boni Paul, who identifies as a man and is an intersex person. He is a former footballer who was selected for the national team to play in the 1998 Asian Games but was subsequently removed, owing to his gender identity.

Intersex people are born with sex characteristics (including genitals, gonads and chromosome patterns) that do not fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

“I had a uterus, one ovary and there was a penis inside. I had both ‘sides’ [reproductive parts],” says Boni. “My type of body exists not just in India but across the world. Athletes, tennis players, footballers, there are many players like me.”

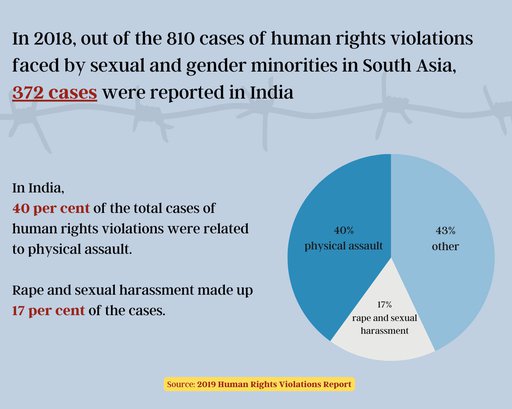

Boni says that he would not leave his house because of fear of society. Members of the LGBTQIA+ community often face threats to their personal safety and abuses that amount to torture or degrading treatment as per international law, notes this report . In fact, in India, physical assault made up 40 per cent of the total cases of human rights violations recorded in 2018, followed by rape and sexual harassment (17 per cent).

This report shows that except for Karnataka, no state government in the country has undertaken awareness campaigns addressing legal recognition of third gender as an identity since 2014. The findings in the report also highlight harassment faced by the transgender community from police officials.

During the first covid-19 lockdown in India, notes Corona Chronicles, several persons with differences in sex development failed to access the required healthcare support due to “minimal knowledge about their specific problems and needs.” Many such reports in PARI Library's Health of Sexual and Gender Minorities section are critical to illustrate and understand the state of LGBTQIA+ health in India.

While the covid-19 pandemic has devastated many folk artists across Tamil Nadu, trans women performers were among the worst hit – with barely any work or income, and no access to aid or state benefits. Sixty-year old Tharma Amma, a trans woman folk artist from Madurai city says, “We do not have a fixed salary. And with this corona [pandemic] we lost even our few chances to earn a living.”

She would earn a total of between Rs. 8,000 and Rs. 10,000 a month for the first half of the year. For the next half, Tharma Amma managed to make up to Rs. 3,000 a month. The pandemic-lockdowns changed all that. “While male and female folk artists easily apply for pension, it is very difficult for trans persons. My applications have been turned down many times,” she says.

Change is coming, at least on paper. In 2019, the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act was passed in the Parliament, applying to the whole of India. The Act says that no person or establishment shall discriminate against a transgender person in relation to education; healthcare services; employment or occupation; the right to movement; purchasing or renting any property; standing for or holding public office; or accessing any goods, accommodation, service, facility, benefit, privilege or opportunity available to the general public.

The Constitution prohibits discrimination of any kind on the grounds of sexual identity. It also says that states can introduce special provisions for women and children to ensure that they are not discriminated against or denied their rights. However, it does not specify that such provisions can be introduced for queer persons.

Cover design: Swadesha Sharma and Siddhita Sonavane

AUTHOR

PARI Library

COPYRIGHT

PARI Library

PUBLICATION DATE

27 ਜੂਨ, 2023