Your university, I told them in 2011, is likely situated, at least partly, on the land of a village whose inhabitants were displaced a record number of times. That is in no way your fault or responsibility. But do be respectful of that.

They were respectful of that – though it came to them as a bit of a shock – the keen and focused bunch of students at the Central University of Odisha, Koraput. They were mainly from the department of Journalism and Mass Communication. And the story of Chikapar disturbed them. A village that was arbitrarily displaced – three times. On each occasion in the name of ‘development’.

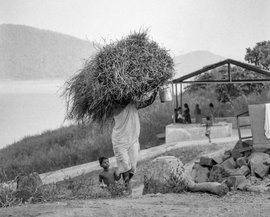

And my mind went back to late 1993-early 1994, when Mukta Kadam, a Gadaba Adivasi ( in the lead photo on top with her grandchild) , told me of how they had been evicted on an angry monsoon night in the 1960s. She had herded her five children before her, luggage on their heads, guiding them through jungle in darkness and pouring rain. “We didn’t know where to go. We just went because the saab log told us to go. It was terrifying.”

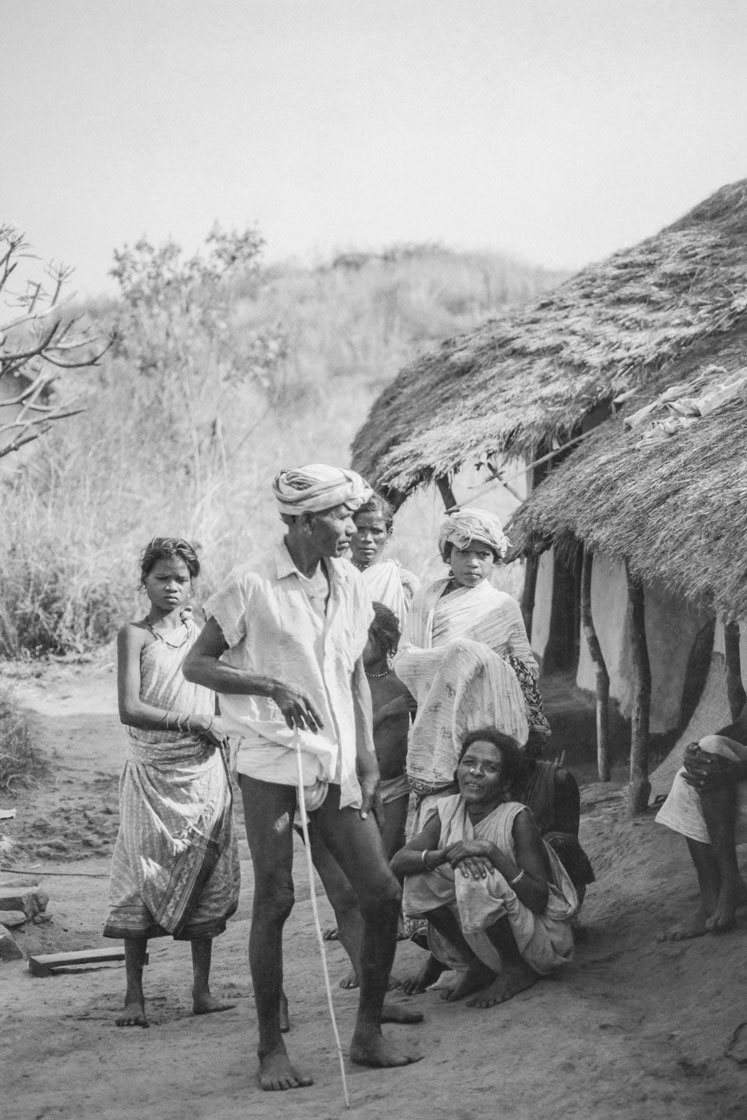

They were making way for the Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) MIG Fighter project. A project that was never to fully arrive or happen in Odisha. But the land was never returned to them. Compensation? “My family owned 60 acres of land,” says Jyotirmoy Khora, a Dalit and activist who continued the struggle for justice of Chikapar’s displaced over decades. “And, many, many years later, we got Rs. 15,000 as [the total] compensation – for 60 acres.” The evictees rebuilt their village once again, on land owned by them and not the government. This they nostalgically also called ‘Chikapar.’

The residents of Chikapar were displaced thrice, and each time tried to rebuild their lives. Adivasis made up 7 per cent of India's population in that period, but accounted for more than 40 per cent of displaced persons on all projects

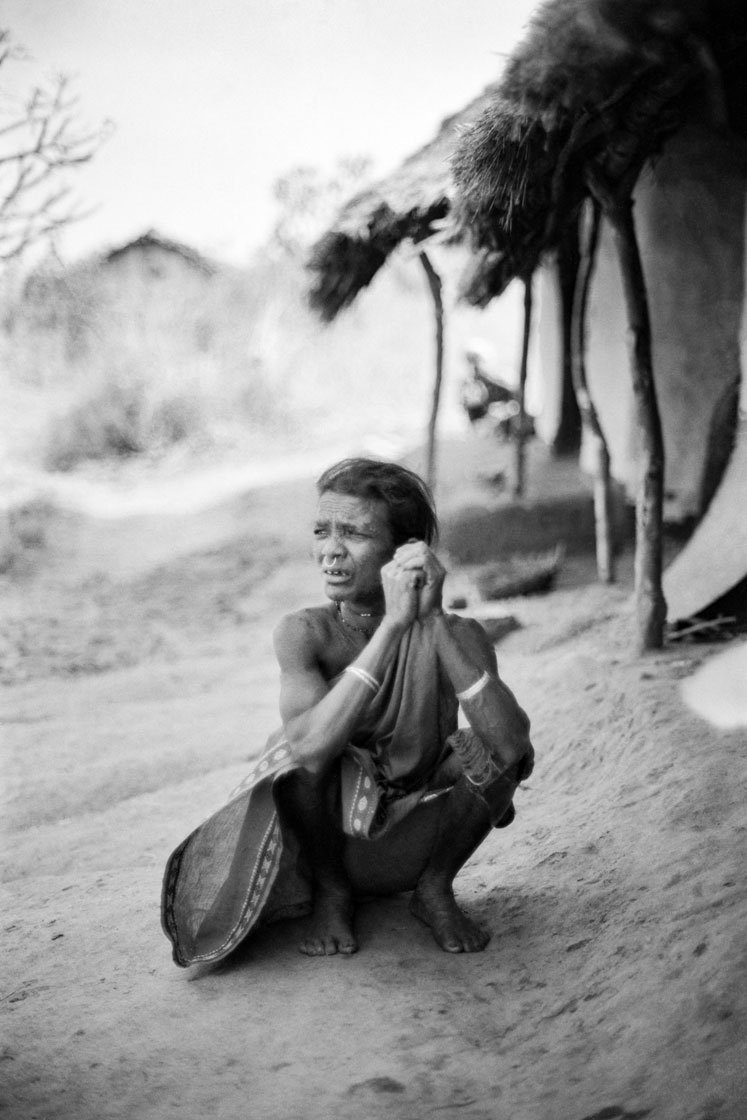

The Gadabas, Parojas and Doms (a Dalit community) of Chikapar were not a poor people. They held quite some wealth in large tracts of land and livestock. But they were mainly Adivasis and some were Dalits. Which made then sitting ducks for displacement. Adivasis have endured the most of forced displacement for development. Over 25 million human beings were displaced by ‘projects’ across India between 1951 and 1990. (And the draft National Policy in the 90s conceded that almost 75 per cent of them “were still awaiting rehabilitation.”)

Adivasis made up some 7 per cent of the national population in that period but accounted for more than 40 per cent of the displaced persons on all projects. For Mukta Kadam and other Chikaparians, worse was to follow. In 1987, they were thrown of out of Chikapar-2 – for a Naval Munitions Depot and the Upper Kolab project. This time, Mukta told me “I left, herding my grandchildren.” They rebuilt yet again at a site you could call Chikapar-3.

When I visited and stayed there in early 1994, they had received notices for a third eviction, possibly for a poultry farm, or probably for a Military Engineering Services depot. Chikapar was literally being chased by development. This would also make it the only village in the world to have taken on the Army, Air Force and Navy – and lost.

Mostly, the land originally taken for the HAL was never used for the officially stated purpose. But some of it and the different sites they had settled on were parcelled out for various uses – to all but the original owners themselves. Some bits of that, I learned in 2011, had gone to institutions of, or affiliated to, the Central University of Odisha. Jyotirmoy Khora was continuing his battle for justice – and to get family members of the displaced some jobs at least, in HAL.

A far more detailed version of this story, in two parts, appears in my book Everybody Loves a Good Drought, but ends at 1995 .