The High Court in Jaipur has a pleasant campus. There’s just one element in its garden that many in Rajasthan find jarring. This is perhaps the only Court complex in the country that boasts a statue of 'Manu, the Law Giver' ( see cover photo ).

There being no evidence that an individual named Manu ever existed, the statue was shaped by the artist’s imagination. It proved to be a limited imagination. Manu here fits celluloid stereotypes of a ' rishi' .

In legend, a person of this name authored the Manusmriti . The smritis are really about norms that Brahmins sought to impose on society centuries ago. Norms that are fiercely casteist. There were many smritis , composed mostly between 200 BC and 1000 AD. They were compiled over a long period of time by several authors. The best known of these is the Manusmriti , extraordinary for the differing standards it applies to different castes – for the same crimes.

In this smriti , lower caste lives were worth little. Take the “penance for the murder of a Sudra.” It is the same as what a person killing “a frog, a dog, an owl or a crow” would have to perform. At best, the penance for the murder of “a virtuous Sudra” is one-16th that to be made for the slaying of a Brahmin.

Hardly what a system based on equality before law needs to emulate. The presence in the court of this symbol of their oppression angers Dalits in Rajasthan. Even more galling, the architect of the Indian Constitution finds no place inside the complex. A statue of Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar stands at the street corner facing the traffic. Manu in his majesty faces all comers to the court.

At the Jaipur High Court: Manu in his majesty faces all who come to the court (left). A statue of Babasaheb Ambedkar at the street corner faces the traffic (right)

Rajasthan has lived up to Manu’s ideals. On average in this state, a Dalit woman is raped every 60 hours. One Dalit is murdered a little over every nine days. A Dalit is the victim of grievous hurt every 65 hours. The house or property of a Dalit family suffers an arson attack every five days. And each four hours sees the registration of a complaint falling into 'Other IPC' (Indian Penal Code) cases. Which means cases other than murder, rape, arson or grievous hurt.

The guilty are rarely punished. Conviction rates range between 2 and 3 per cent. And many offences committed against Dalits never even reach the courtroom stage.

Countless complaints end up closed and buried with 'FRs' (final reports). Genuine and serious cases are often scuttled.

“The problem begins right in the village itself,” says Bhanwari Devi, whose daughter was raped in a village in Ajmer district. “The villagers hold a caste panchayat. They pressure the victims to patch up with their attackers. They say: ‘why go to the police? We’ll solve the problem ourselves’."

The solution usually means the victim gives in to the oppressor. Bhanwari was held back from going to the police.

In any case, the very act of a Dalit or Adivasi entering a police station brings its own risks. What happens when they do go? In Kumher village in Bharatpur district, some 20 voices answered at the same time: “Two hundred and twenty rupees entry fee,” they said. “And many times that sum if you want them to move on your complaint.”

Where an upper caste person has attacked a Dalit, the police try to dissuade the victim from filing a complaint. “They’ll ask us,” said Hari Ram, “Kya? Baap bete ko nahin marte hain, kya? Bhai bhai ko nahin marte hain kya? (Doesn’t a father strike his son? Doesn’t a brother hit his brother now and then?). So why not forget it and drop the charge’?”

“There’s another problem,” says Ram Khiladi, laughing. “The police take money from the other side as well. If they pay more, that’s the end for us. Our people are poorer and can’t afford it.” So you can actually pay Rs. 2,000 to Rs. 5,000 and lose it.

Next, the policeman coming down to investigate can end up arresting the complainant. This is more likely to happen if the latter is a Dalit complaining against an upper caste person. Often the constable belongs to the dominant caste group.

“Once when the upper castes attacked me, the DIG posted a policeman outside my door,” says Bhanwari in Ajmer. “That havaldar spent all his time boozing and eating in the Yadav houses. He even advised them on ways of dealing with me. Another time, my husband was beaten up badly. I went to the station alone. They wouldn’t file an FIR and abused me: ‘How dare you come here on your own, you a woman (and a Dalit at that)?’ They were outraged.”

Back in Kumher, Chunni Lal Jatav sums it up: “All the judges of the Supreme Court do not have the power of a single police constable.”

That constable, he says, “makes or breaks us. The judges can’t re-write the laws and have to listen to arguments from learned lawyers of both sides. A havaldar here simply makes his own laws. He can do almost anything.”

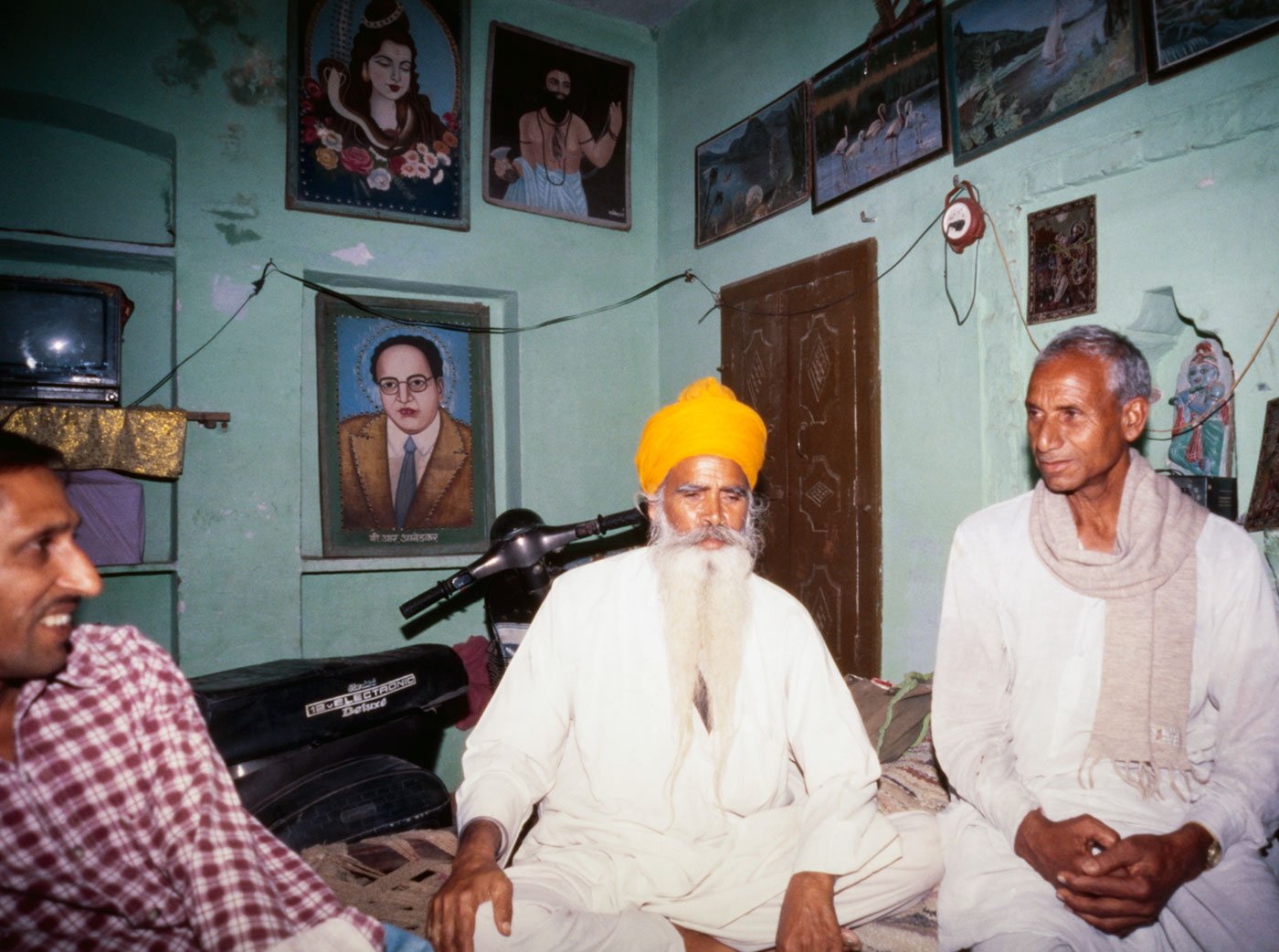

Chunni Lal Jatav (right) of Kumher says astutely: 'All the judges of the Supreme Court do not have the power of a single police constable'

If, after much effort, an FIR is actually lodged, fresh problems arise. That’s apart from the “entry fee” and other moneys paid. The police delay recording witnesses’ statements. And, says Bhanwari, “They also deliberately fail to arrest some of the accused.” These are just declared ‘absconders’. The police then plead inability to proceed without their capture.

In many villages, we came across instances of “absconders” actually moving about quite freely. This, and the inertia in getting witnesses’ statements, leads to fatal delays.

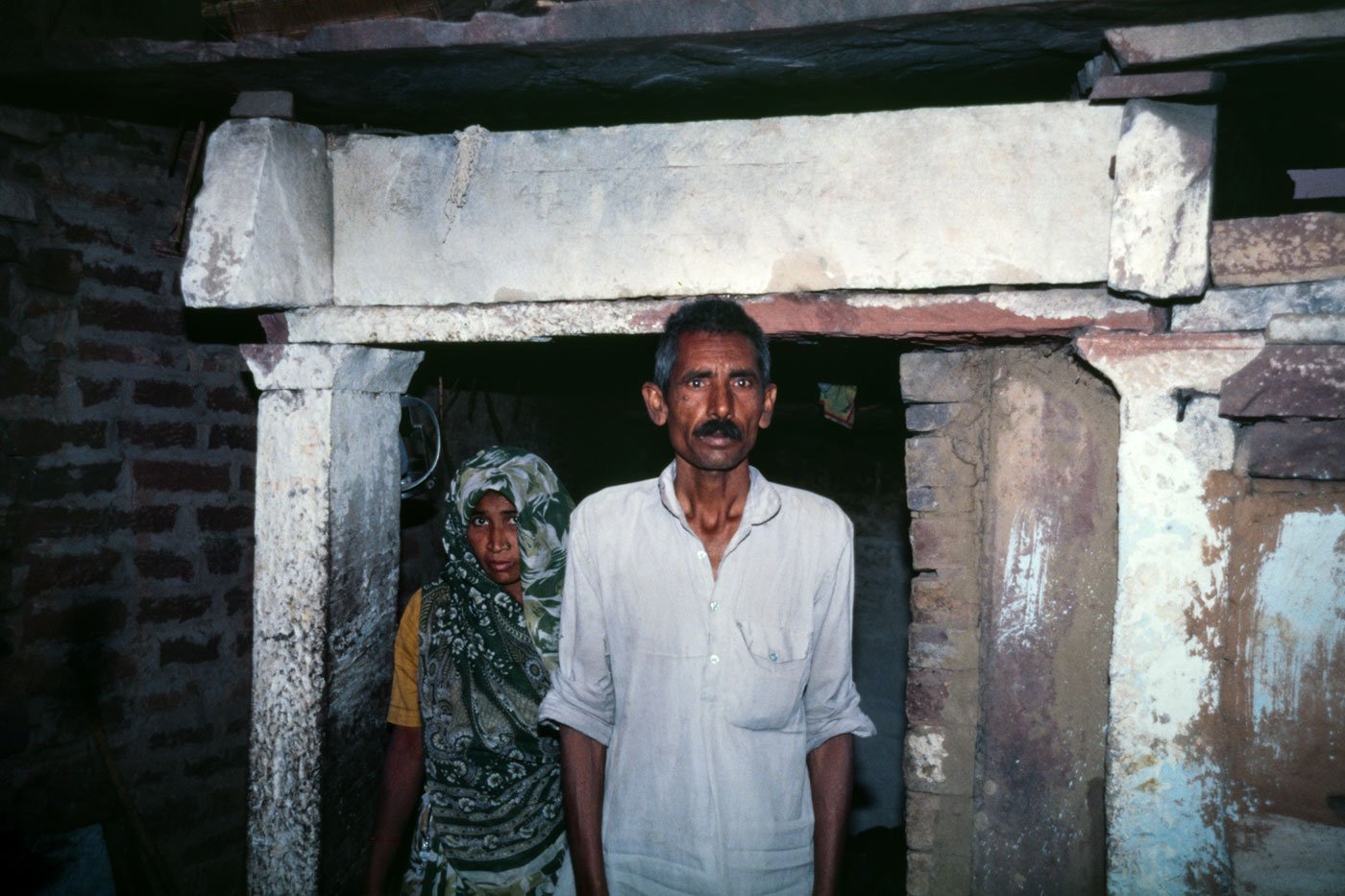

It also leaves the Dalits at the mercy of their attackers in the village, often forcing them to compromise their own case. In Naksoda in Dholpur district, the upper castes inflicted a unique torture on Rameshwar Jatav. They pierced his nose and put a ring of two threads of jute, a metre long and 2 mm thick, through his nostrils. Then they paraded him around the village, leading him by the ring.

Despite the

media attention the case got, all witnesses– including Rameshwar’s father,

Mangi Lal –

have turned hostile. And yes, the victim himself has absolved

those charged with the crime.

In a case of an atrocity against a Dalit in Naksoda village, the witnesses, including the victim's father Mangi Lal (right), turned hostile. 'We have to live in this village', he says. 'Who will protect us?'

“Any atrocity case,” senior advocate Banwar Bagri, himself a Dalit, told me at the court in Jaipur, “has to be processed very quickly. If delayed beyond six months, there is hardly any chance of conviction. The witnesses can be terrorised in the village. They turn hostile.”

There is no witness protection programme. Besides, delays mean that already biased evidence gets further rigged as the upper caste group in the village strikes a deal with local police.

If the case does get off the ground, there’s the problem of lawyers. “All vakils are dangerous,” says Chunni Lal Jatav. “You could end up with someone who bargains with your enemy. If he gets paid off, you’re finished.”

And costs are a real problem. “There is a legal aid scheme, but it’s too complex,” says advocate Chetan Bairwa, among the few Dalits at the High Court in Jaipur. “The forms need details like your yearly income. For many Dalits on daily and seasonal wages, this is confusing. Also, awareness of their rights being low, many don’t even know about the aid fund.”

That Dalits are poorly represented in the legal fraternity does not help. At the court in Jaipur, there are about 1,200 advocates, of whom about eight are Dalits. In Udaipur, that’s nine out of some 450. And in Ganganagar, six out of 435. At higher levels, under-representation is worse. There are no Scheduled Caste judges at the High Court.

There are Dalit judicial officers or munsiffs in Rajasthan, but these, says Chunni Lal in Kumher, don’t matter. “They are too few and they don’t even want to be noticed, let alone draw attention to themselves.”

When a case reaches the court, there is the peshkar [court clerk] to take care of. “If he isn’t paid off, you can have hell with your dates,” I was told in several places. And anyway, “the whole system is so feudal,” says Chunni Lal. “That’s why the peshkar , too, has to have his cut. In several magistrates’ offices, all the judicial officers sit and have lunch that is paid for by the peshkar . I recently exposed this to journalists who wrote about it."

And lastly, there’s the abysmally low conviction rate itself. But that isn’t all.

“You can have a good judgement,” says Prem Krishna, senior advocate at the High Court in Jaipur. “And then find that the attitude of the implementing authorities is terrible.” Prem Krishna is also president of the Peoples Union for Civil Liberties, Rajasthan. “In the case of the Scheduled Castes there is both economic inability plus a lack of political organisation. Even Dalit sarpanchas are trapped in a legal system they can’t fathom.”

In Raholi, suspended Dalit sarpanch Anju Phulwaria, having spent tens of thousands of rupees fighting her case, faces financial ruin

In Raholi, Tonk district, suspended sarpanch Anju Phulwaria, having spent tens of thousands of rupees fighting her case, faces financial ruin. “We’ve taken our girls out of a good private school and put them in the government school.” The very school where teachers were responsible for instigating students to deface Dalit properties.

In Naksoda, Mangi Lal has spent over Rs. 30, 000 fighting the nose-piercing case – one on which he and his son, the victim, have given up. The family has sold a third of its meagre land to meet the costs.

Rajasthan’s new chief minister, Ashok Gehlot, appears keen to change some of this. He says his government is willing to consider a random survey of 'FRs' – final reports or closed cases. If deliberate cover-ups are found, “then those guilty of undermining the investigation will be punished,” he told me in Jaipur. Gehlot intends to bring in “amendments to the panchayat laws to ensure that weaker sections are not wrongfully deposed” from posts like sarpanch .

Quite a few sarpanchas like Anju Phulwaria were, in fact, victimised during the Bharatiya Janata Party regime. By reversing that process, Gehlot can only gain politically. But he has a huge, hard task ahead. The system’s credibility has never been lower.

“We have not the slightest faith in the legal or judicial process,” says Ram Khiladi. “We know the law is for the big people.”

This is, after all, Rajasthan, where Manu casts a long shadow inside the court. And where Ambedkar is an outsider.

The crime data in this two-part story for the period 1991-96 were from the report of National Commission for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes for Rajasthan of 1998. Many of these numbers might actually have worsened since then.

This two-part story was originally published in The Hindu on July 11, 1999. It won the first Amnesty International Global Award for Human Rights Journalism, in the prize's inaugural year, 2000.