Ramesh Jagtap has had a rough day. He quarrelled with his wife, Gangubai, in the morning. After the fight, she consumed pesticide. He took her in a shared rickshaw to the district’s civil hospital in Osmanabad city, 30 kilometres from Satefal village. “My heartbeats were pounding like never before through the journey,” he says. “Fortunately, we reached in time for the doctors to treat her.”

He rushed back to Satefal in the afternoon. The local branch of the district’s cooperative bank was disbursing payments to settle claims made by farmers under the government’s crop insurance scheme. “I got back and stood in line for over an hour,” Jagtap says. “But the bank had only released a part of the sum.” And that was given to farmers who had taken a token ahead of him.

Jagtap, 50, who cultivates soybean, jowar and wheat on his five acres, could well lose count of the problems he might wake up to tomorrow. He already has a bank loan of Rs. 1.20 lakhs, and owes Rs. 50,000 to a private moneylender. “I had borrowed money during previous years of drought and for my daughter’s marriage,” he says. “Moneylenders abuse us every day as we delay their payment. The fight with my wife started over this. She could not take the pressure and humiliation and poisoned herself in the heat of the moment. I need to repay my loans. I need money to prepare my land ahead of the monsoon season.”

The desperation for funds forced Jagtap to rush back to Satefal, leaving Gangubai in the hospital. He is eligible to receive Rs. 45,000 from the government as crop insurance for the rabi season of 2014-15. On March 4, the government deposited Rs. 159 crores, which belong to 268,000 farmers like Jagtap, in the Osmanabad District Central Cooperative Bank (ODCC). But two months later, only Rs. 42 crores have been distributed.

'Moneylenders abuse us every day as we delay their payment. The fight with my wife started over this. She could not take the pressure and humiliation and poisoned herself'

On April 5, the government deposited Rs. 380 crores as crop insurance for the 2016-17 kharif season. This, too, the famers have not received.

Sanjay Patil-Dudhgaonkar, a farm leader in Osmanabad, who went on a three-day hunger strike on April 19 after the bank kept delaying payments, alleges the ODCC has invested the money and is eating up the interest. “This is the time when farmers start looking for credit,” he says. “It is a critical period and cash in hand goes a long way. Why should a farmer wait months for his own money?” His strike ended when the bank promised to pay up in 15 days – a promise that’s not been kept.

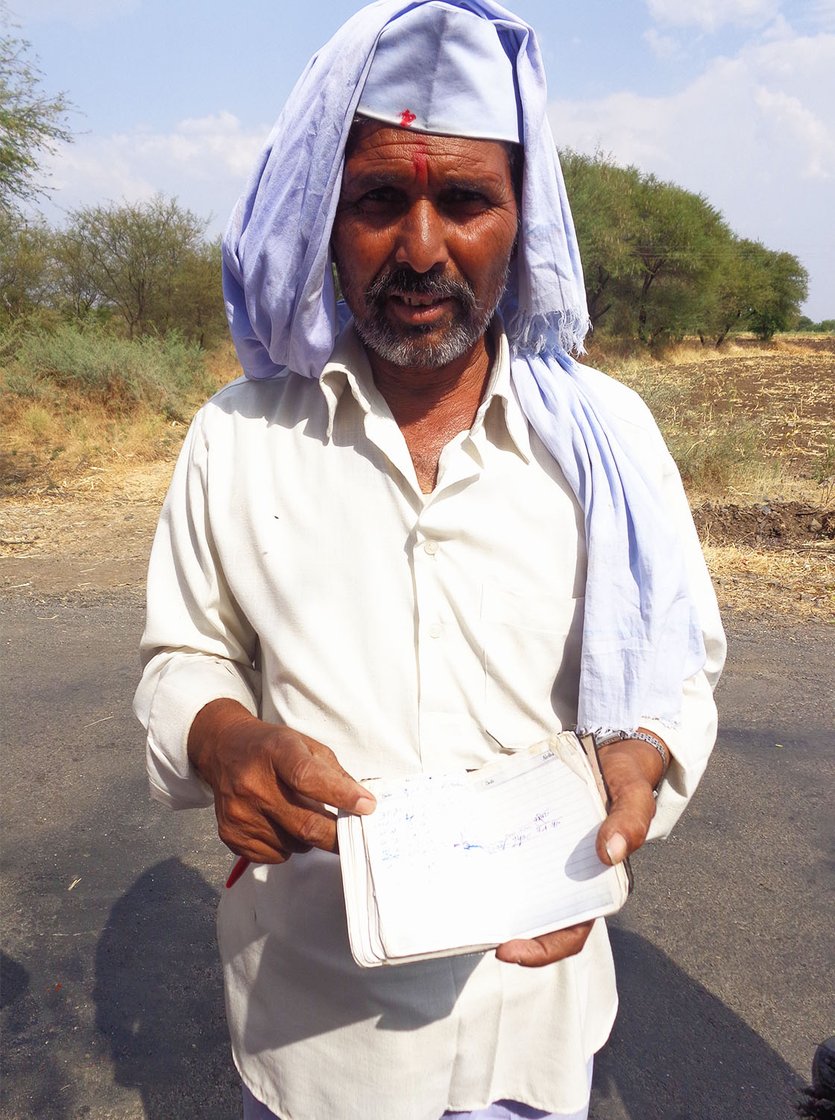

Chandrakant Ugale, 52, from Satefal, says the incessant running around for money makes it difficult to focus on preparing the farmland for the kharif season. “It is not easy to get seeds and fertilisers on credit anymore. Everybody knows our financial condition. Nobody trusts the farmer with money.” The bank is yet to give Ugale his crop insurance payment of Rs. 18,000.

V. B. Chandak, chief officer (administration and accounts), at ODCC, says the Reserve Bank of India has not released enough notes and the bank is struggling to pay up. “We are still distributing as quickly as we can,” he says. “We will try to clear the funds within 15 days.”

Left: The bank is yet to give Chandrakant Ugale, a farmer from Satefal, his crop insurance payment of Rs. 18,000. Right: Baburao Navle, a farmer from Shelgaon village, whose principal loan of Rs. 4 lakhs has spiralled to Rs. 17 lakhs

Even as Chandak tries to defend his bank, 10-15 people barge into his cabin, furious. They throw documents at him, accuse him of rupturing their financial plans and demand cash. They all want to withdraw their fixed deposits, which have matured, some for years. Among them is Sunita Jadhav, around 45 and a widow, who wants to withdraw her deposit of Rs. 30.000, which matured a year ago. “My daughter is getting married on May 7,” she says. “I am not going back without my money.”

Jadhav lives in Jalkut village, 50 kilometres from Osmanabad city. She has spent nearly a day’s wage – Rs. 200 – on commuting to the bank. And she has visited the ODCC several times for more than six months. She takes out a wedding card from her purse and says, “I have worked hard to save up this amount.” Jadhav works as a labourer at a brick kiln. Her brother, who lives with her, recently lost his job as a waiter at an eatery in Jalkut. “A day spent in begging for my own hard-earned money means losing out on my daily wage as well,” she says. “The local branch asks me to visit the headquarters. Here they tell me to go to the local branch.”

Chandak listens to all of them and politely says the bank has no funds. He is right. The ODCC is in a mess, to put it mildly. The bank is unable to repay close to Rs. 400 crores of fixed deposits, but is doing little to recover its non-agricultural loans of over Rs. 500 crores. Of this, just two sugarcane factories in the district – Terna and Tuljabhavani – owe the bank Rs. 382 crores.

Moreover, the loans that the ODCC has given to farmers – this credit is routed through 467 Vividh Karyakari Seva Sahakari Societies – point at large-scale corruption. The Societies owe the ODCC Rs. 200 crores more than the amount to be recovered from farmers. Where this money has gone is anybody’s guess.

The bank is unable to repay close to Rs. 400 crores of fixed deposits, but is doing little to recover its non-agricultural loans of over Rs. 500 crores

While doing little to address these issues, the ODCC had threatened 20,000 farmers who owe the bank Rs. 180 crores with public humiliation and sent them notices in mid-November. The threat was retracted only after reports in the news media. “The non-agriculture debts belong to influential [politically-connected] people,” says a bank official. “When we visit them for a reminder, we start by saying we were in the vicinity and then mention the loan as a passing reference.”

While not recovering debts from defaulters, the ODCC ‘adjusted’ crop insurance payments that farmers were to receive against crop loan repayments the farmers were yet to make. ‘Adjust’ here means an amount from the insurance payout due to them was deducted as part repayment towards the crop loans they had taken. “The collector said on March 22 that we can ‘adjust’ up to 50 per cent of the amount,” says Chandak. That is, as much as half the insurance payout due to a farmer could be deducted in this fashion. “On March 31, the decision was rolled back. We will return the money of those we have adjusted if we get clear-cut orders from the government.”

Dudhgaonkar says it is no surprise that the government diverted Rs. 5 crores of insurance payments in this way between March 22 and March 31, while recovering not even Rs. 50 lakhs of non-agricultural loans in the previous six months.

The ODCC has been aggravating the stress of farmers in other ways too. A few years ago, the bank started restructuring the debts of farmers by clubbing their term loans and crop loans together. The interest rate on a crop loan (for agricultural activities like buying seeds and fertilisers) is 7 per cent; of this, 4 per cent is paid by the state. A term loan (used for capital investment) could charge double the interest rate. Through restructuring, the bank merges the two loans and converts them into a new term loan, which magnifies the farmers’ dues.

Left: Sunita Jadhav of Jalkut village: 'My daughter is getting married on May 7. I am not going back without my money'. Right: Furious depositors at the Osmanabad District Cooperative Bank, demanding their money back

Baburao Navle, a 67-year-old farmer from Shelgaon village, says his principal loan amount was just under Rs. 4 lakhs. After restructuring, it has spiralled to Rs. 17 lakhs over the years. The bank emphasises the farmers’ consent to the conversion, but the farmers claim they have been deceived. “We were told to sign a document to avoid raids and confiscations at our homes,” says Navle, who cultivates wheat, jowar and bajra on his four acres. Twenty five farmers from his village collectively owe more than Rs. 2 crores to the ODCC – the original amount was around Rs. 40 lakhs. “Is it not the bank’s responsibility to inform us fully before asking for our signatures?”

Almost all the district cooperative banks of Marathwada – where many farmers have accounts – are on thin ice. The banks, unable to confront powerful defaulters and in financial distress themselves, can barely be the economic backbone of farmers – who are then driven to private moneylenders.

Back in Satefal, while Jagtap is talking to me about his problems, several people passing by on their motorbikes join in. Everyone is returning from the bank. A few relieved, many dejected. The branch has distributed crop insurance only to 71 farmers from Satefal that day. Jagtap has decided to go back to the hospital. “My wife will ask if I received the insurance,” he says. “What will I tell her…?”