India has increased its school enrolment by 300 million children this decade, but what is the quality of education? Each year in January, a citizen’s report card (ASER, or Annual Status of Education Report ) is presented on what children are learning in schools – can they read and comprehend basic text, and do they understand numbers?

The report’s qualitative findings are a useful antidote to the government's bland statistics. ASER tests all school-going children for basic learning levels, seeing if they can read texts and solve numerical problems of Class 2. In 2008, for example, the survey found that 44 per cent of school children cannot solve Class 2 maths problems involving basic subtraction or division.

The three-month-long effort, spearheaded by the non-governmental organisation Pratham, brings together over 30,000 motivated volunteers – from students and scientists to investment bankers and pickle-makers – who fan out across India’s towns and villages to test children and look at school infrastructure. An estimated 7 lakh children in 3 lakh households are part of the exercise this year.

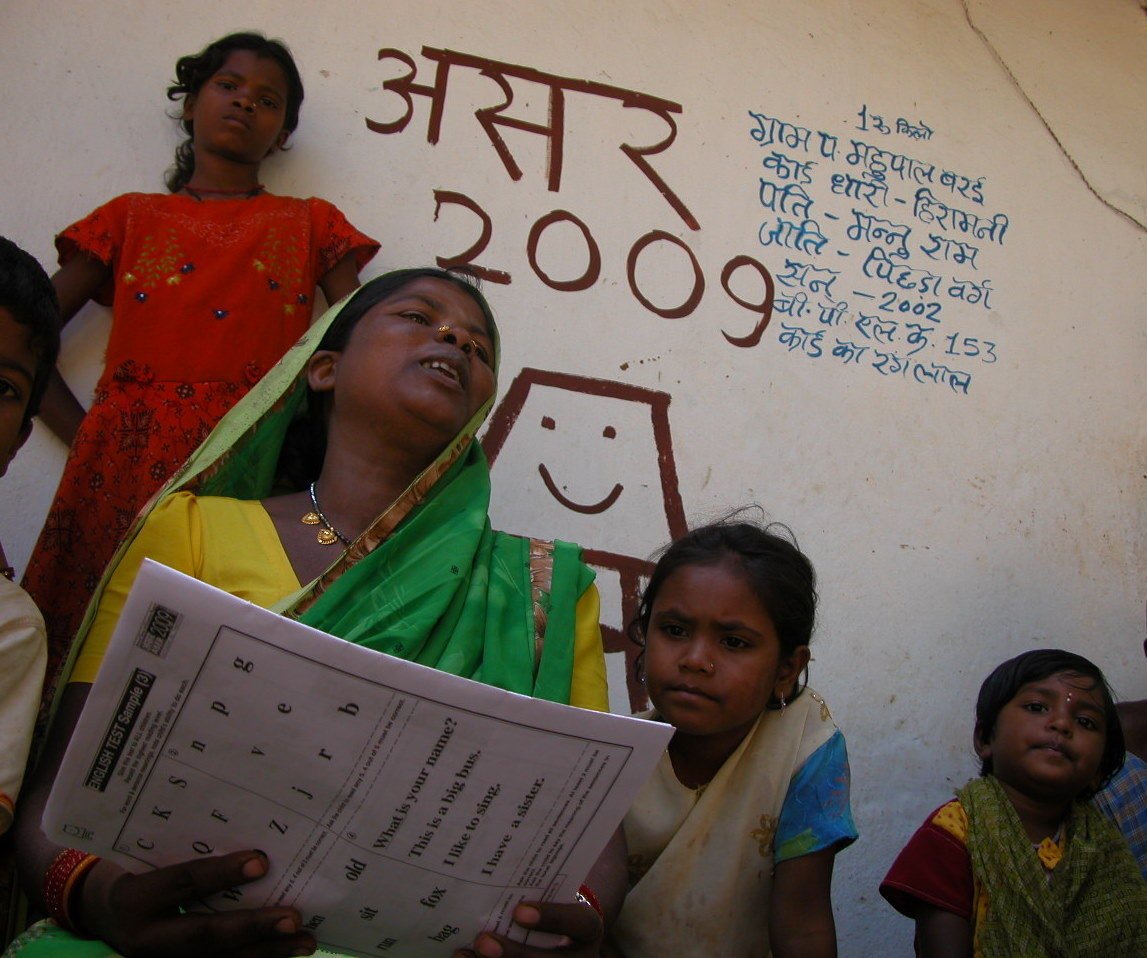

Left: Chhattisgarh has eliminated the career teacher over the past decade, relying entirely on contractual teachers like 21-year-old undergraduate Navan Kumar. Right: After enrolling in the National Adult Literacy Mission, paddy farmer Hiramati Thakur now reads basic texts haltingly

When Pratham instructor Swami Alone tested Gita Thakur, nine, one look at numbers was enough to make the Class 4 child cry. Subtracting 27 from 39 was a struggle, and she finally arrived at an answer – 116. Here’s one possible reason why: her village school has one teacher instead of the mandatory four.

The state of Chhattisgarh has eliminated the career teacher over the past decade, relying entirely on ill-qualified para-teachers hired contractually for government schools on lower pay. Undergraduate Navan Kumar, 21, has filled up an application to become such a contract school teacher. When surveyors tested him, he could not divide 919 by 9. Alone said: “In several villagers we find, teachers do not know basic maths themselves, and so children also learn wrongly.”

India has the damaging distinction of being the country with the most illiterates in the world – over 300 million can neither read and write nor work with numbers. This year, the ASER survey is also testing adult female literacy levels, to see if there is a positive causal link between a mother and her children’s education. Paddy farmer Hiramati Thakur, in her 50s, was yanked out of school as a child, to get married. Her children, now adults, are also dropouts. After enrolling in the National Adult Literacy Mission this year, Hiramati now reads basic texts haltingly. “If a poor person does not study today, he is reduced to a coolie’s life. Whenever I have any free time, I sit with a book, and teach myself.” She smiled, as she asked surveyors: “Can I get a job now?”

Left: The village school is a three-room building without steady water facilities or toilets. Right: BEd students like Madhav Jadhav (foreground) and Satya Prakash fill in while contract teachers are on strike, demanding pay hikes

The village school is a three-room building from Classes 1-7, without dedicated drinking water facilities or any toilets (“ Uska proposal chal raha hai ” [The proposal for that is in process] said a harried official from the Tribal Welfare Department). There wasn’t a single teacher too in the school on this Monday morning.

With thousands of contract teachers on a strike across the state demanding a hike from their current pay of between Rs. 4,000-6,000, BEd students like Madhav Jadhav, 25, and Satya Prakash are filling in, teaching the children three days a week. Classes 1-3 were being taught simultaneously in a cramped room. Jadhav said: “Children’s levels are very low, and they cannot even do basic problems. There is a lot of work to be done.”

The author spent a weekend on the survey in Parchanpal village of Bastar, 290 kilometres south of Chhattisgarh’s capital Raipur, for this snapshot of India’s troubled public schools.