The forest enters the classroom at Vidyodaya School, Gudalur, when ‘Shanthi Teacher’ starts the mathematics session. Adivasi children, mostly nine-year-olds in this class, scurry outside, climbing trees and scouring the forest floor for long sticks. Later, they will mark these into metre lengths and measure the walls of their homes. Lessons on simple measurement begin this way.

Much of the curriculum at this school in Gudalur taluk of Tamil Nadu’s Nilgiris district incorporates the forests and the Adivasi way of life. Morning assembly has tribal songs and dances. Afternoons are spent learning tribal crafts. Regular ‘nature’ walks in the forest, sometimes led by one of the parents, teach the students about plants, pathways, observation and the importance of silence.

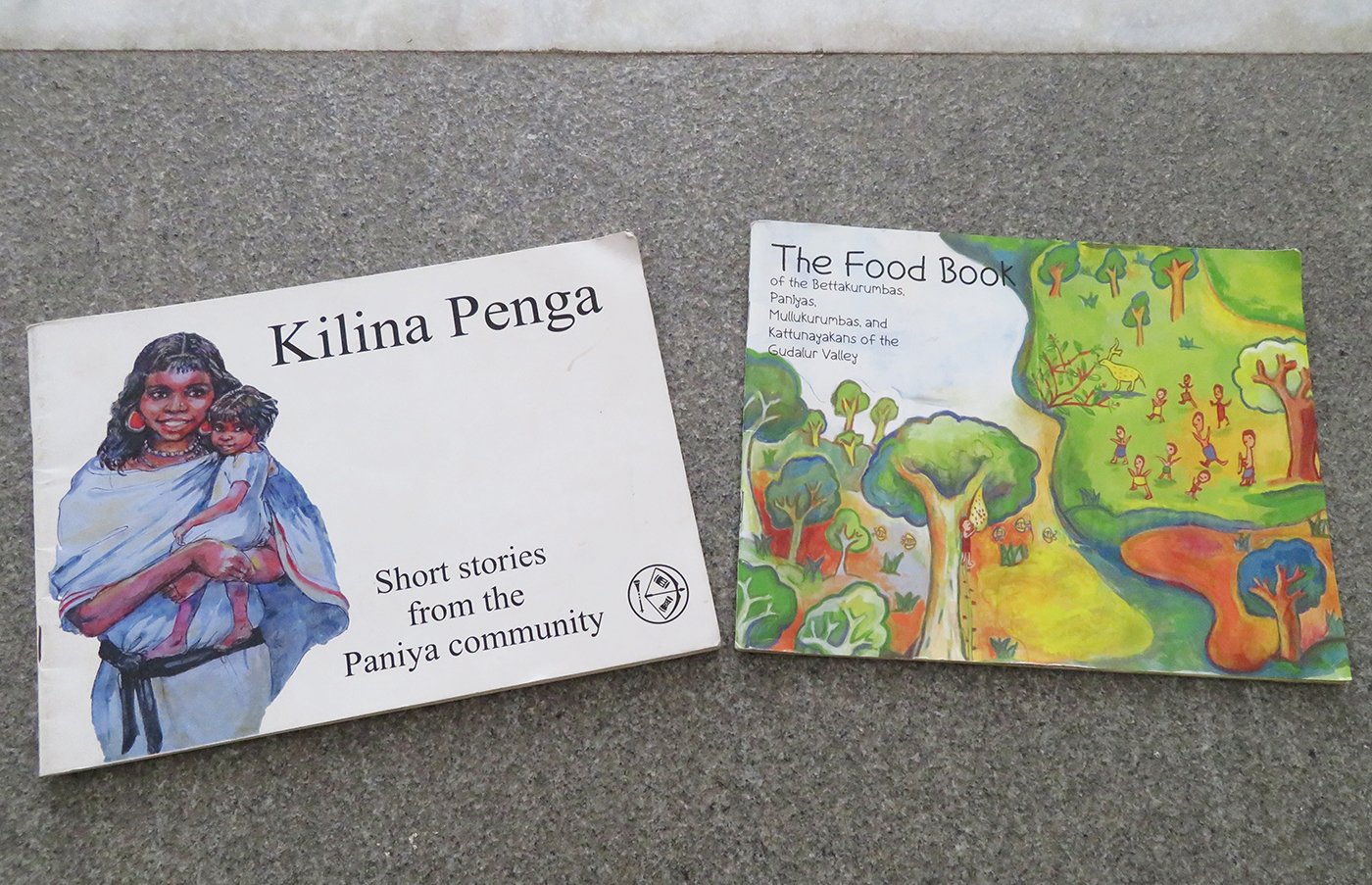

A Vidyodaya textbook called The Food Book has exercises that draw on the hunting, fishing, culture and cultivation traditions of local tribes. In library class, a student can pick up Kilina Penga ( Sister of the Parrots ), a book of short stories of the Paniyan tribe, curated by the school. Parents often visit, sometimes as guest lecturers on tribal customs. “We want to ensure that schooling nurtures Adivasi culture and does not alienate tribal children from their parents,” says Rama Sastry, former principal and main architect of the school’s inclusive curriculum. Having Adivasi teachers, sympathetic and committed to these aims, helps. As Janaki Karpagam, a senior teacher and Paniyan Adivasi herself, puts it: “If our culture is taught in schools, there is no shame and children will never forget.”

The students sing Adivasi songs during their morning assembly (left) and use sticks found in the forest for measurments in maths class (right)

Vidyodaya was started in the early 1990s as an informal primary school. In 1996, the Adivasi Munnetra Sangam, a representative body of tribals in Gudalur, approached Vidyodaya, asking that it become a model school. “The tribals had been led to believe that they were ‘uneducatable’, but when they saw the few tribal children in our school flourishing, they were convinced that it was the system and not the children at fault,” says B. Ramdas, managing trustee of the Viswa Bharathi Vidyodaya Trust, which manages the school. He ran the school with his wife Rama, the principal, in their home.

Parents came and built a mud and thatch room to get them going, extending from the home-school. Later, to increase enrolment, grandparents were signed up as escorts – travelling up to five kilometres, rounding up the young ones and bringing them to school with stories and songs to keep them engaged on the journey. They were paid a ‘tea allowance’ of Rs. 350 per month by the school, as they sat in the tea shops waiting for the return journey!

Now Shanthi Kunjan, 42, a Paniyan Adivasi, heads this free primary school in the Nilgiris district. Both teachers and students are Adivasis, mostly Paniyan. The rest are Betta Kurumba, Kattunayakan and Mullu Kurumba. The Census of India 2011 counts 10,134 Paniyans, only 48.3 per cent of them literate. That’s 10 per cent lower than the average for all Scheduled Tribes, and way below the national literacy rate of 72.99 per cent.

With a BA in History, Shanthi defies the statistics of her tribe. At her home in Valayavayal hamlet near Devala town, 17 kilometres away, the shelves of the sitting room are filled with story cards and small story books that the neighbourhood children help themselves to. The calendar is circled with exam dates for her school-going son and her daughter’s post graduate books are neatly stacked. Learning and academics vie for space with a television set and the jumble of everyday life.

The Adivasi way of life is woven into the Vidyodaya school's curriculum. In the afternoons, students make bead chains and learn tribal crafts (right)

Schooling was not seen as a priority for a young Adivasi girl living in the forests of the Nilgiris. The eldest of eight children, Shanthi spent most of her childhood playing and caring for her younger siblings under the watchful eye of her grandparents. Her parents were daily wage labourers – her father scouring the forests to procure the prized leaf kuvaillai used in packing fish, and her mother working on the tea estates of this area. At age six, she joined the Government Tribal Residential (GTR) school in nearby Devala.

There are 25 GTRs spread over the Nilgiris district, meant to serve tribal children – with free tuition, food and board. But most teachers are from the plains, rarely show up, and wait to be transferred, says Mullukurumba Gangadharan Payan, 57, a former GTR educator. “The classroom and hostel are all just one room. The facilities are poor, so children don’t stay overnight. Computers and books exist but are locked up.”

“I learnt nothing,” says Shanthi, speaking for the many Paniyan children with her. She only spoke Paniyan and understood little as the medium of instruction was Tamil. The lessons are all about rote learning. Incidentally, India’s Constitution (Article 350 A) exhorts every state “to provide adequate facilities for instruction in the mother-tongue at the primary stage of education to children belonging to linguistic minority groups...”

Today, as an experienced teacher, she sees the flaws clearly. “If the children in the school can’t communicate, they become scared and prefer to stay away. That is how fear begins.”

During library class, students from the Paniyan, Betta Kurumba, Kattunayakan and Mullu Kurumba tribes can read books about their local traditions

Most children at the GTRs are first generation learners, whose parents and grandparents cannot help them with school. So attendance is poor, learning negligible and dropping out common. All of Shanthi’s siblings went to GTRs, and all but one dropped out. This is not unusual, as Census data shows: between Class 1 and 10, the dropout rate for Adivasi communities is 70.9 per cent. For other social groups, it is 49 per cent.

Shanthi’s education took a turn for the better when missionary sisters urged her parents to send Shanthi with them to their school in Periyakodiveri village near Sathyamangalam town in Erode district, five hours away by road. She would stay there for the next five years, completing her Secondary School Leaving Certificate (Class 10) and then returning home to marry Kunjan, a Paniyan boy and unskilled labourer.

Once back in Devala, many wanted to recruit Shanthi; she was the most highly educated Adivasi in the area. She turned down nursing job offers. But when a team from ACCORD, a Gudalur-based non-governmental organisation, came calling for educated Adivasis to join a two-year teacher training programme, she was ready. “I always wanted to be a teacher, the kind that wields a large stick and bosses others around,” she says, laughing.

Left: Shanthi, a first-generation learner, with her mother, Karupri. Right: After school, brothers Murali and Arjun walk home to Gundital, Sreemadurai

Her husband Kunjan, who has a few years of formal schooling, was supportive and they even moved house to be close to the training centre. Her mother and sisters would drop in to help with the housework and care for her infant daughter. Her course mates were 14 other young Adivasis and they were given a monthly stipend of Rs. 800. The course ran from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. every day, and on Saturdays there were visits to tribal villages to assess the challenges they would soon be up against.

Despite Shanthi’s determination and her family’s support, it was tough to juggle roles. Some of her batch mates gave up, but she stayed: “I was very interested to learn. I had a chance to try science experiments – something I had never done.” The lessons on tribal history made her look at herself and her community differently. She completed her training and went on to study further, earning a Bachelor’s degree in History through Madras University’s Distance Education Programme.

Shanthi joined Vidyodya 15 years ago and is proud of the fact that today all young Paniyan children in her neighbourhood attend one of the over 100 schools registered in Gudalur taluk. But areas like Muchikundu, where she lived before an elephant tore down her house, are quite remote and enrolment is still a challenge. “I want to reduce dropout rates by talking to parents,” she says.

Many of the parents are wage labourers earning Rs. 150 a day and they worry about money for fees, uniforms, books and transport, which could range from Rs. 8,000 to Rs. 25,000 annually, depending on the kind of school – government or private. Travel costs especially from the more remote areas can be high too. Vidyodaya charges no fees and subsidises transport, each child having to pay Rs 350 per year, and only if they can.

Meanwhile, back in school, the bell has rung and children begin to sweep their classroom, and put away books, files and craftwork. Shanthi is checking the register and signing out. The local jeep-taxi is waiting and she gets in along with some of the children from her neighbourhood, the youngest ones vying for her lap on the 45-minute journey home through the forests and towns of the Nilgiris. It’s just another day at school for her and her Adivasi colleagues and students.