Jai Sakhale sings about people migrating from the village to work in Mumbai, and about the mother who worries for her son working hard in the demanding city

In Mumbai city, money doesn’t grow on trees

My son works hard, his bones are wrung out of energy

“Many women from the villages saw their sons go away to Mumbai to work at the cotton mills. They would stretch their arms and twist them at the wrists continuously when they worked at the mill,” said Kusumtai Sonawane about these

ovi

when we spoke on the phone in June this year. “Some men also worked at construction sites, carrying headloads of gravel or sacks of cement on their backs. At the end of the day, they felt so tired, as if their bones were wrung dry of strength. And the mother felt that a drop of her son’s sweat was worth a lakh of rupees.”

Then, pausing for a moment, she added, “There were others too, who cleaned the city’s gutters.”

Kusumtai, from Nandgaon village of Mulshi

taluka

in Pune district, was present when the original Grindmill Songs Project team recorded Jai Sakhale singing the songs featured here, two decades ago. The songs were recorded on audiotapes in October 1999 and later converted into digital formats. Jai Sakhale was from Lavharde village in Mulshi. She died in 2012. Some of her other songs have been published by PARI (see

The farmer and the rain song

).

The nine

ovi

in this instalment take us back to the times when people from rural Maharashtra migrated to Bombay (now Mumbai). Historical records show that the growth of Bombay into a major trading town in the mid-1700s, and the establishment of the Port Trust and textile mills in the 1800s, brought people from other parts of the country to the city in search of work and income. Rural migrants from the hinterlands of Maharashtra came to the growing city mainly from the Konkan coast and Pune, Nashik and Satara and other towns and villages in the Western Ghats region.

The late Jai Sakhale (left) and her daughter, Lilabai Shinde, with her mother's photo

The tales of life in Mumbai and comparisons with the rural way of living form the basis of these couplets. One song unravels the compulsions of a new kind of existence and the changes it brought to human relationships, even between siblings. Every type of give and take between people living in the city held a commercial value, and this stark reality of life is juxtaposed against the traditional and the familial that was the norm in the villages.

These

ovi

were probably composed in the pre-Independence period and handed down through generations of village women. The first couplet refers to the mother’s pride that her son has learnt to speak English – the language of the

sahebs

– and so he is offered a chair to sit on. In the second

ovi

, the singer compares the crowded city of Mumbai to a place where she finds that every street is full of glass tumblers. And there are so many people that everyone looks alike; it is difficult for the mother to find her son. The tumblers look identical but only one will quench her thirst. She seems to ask: ‘Where is the glass that is my son?’

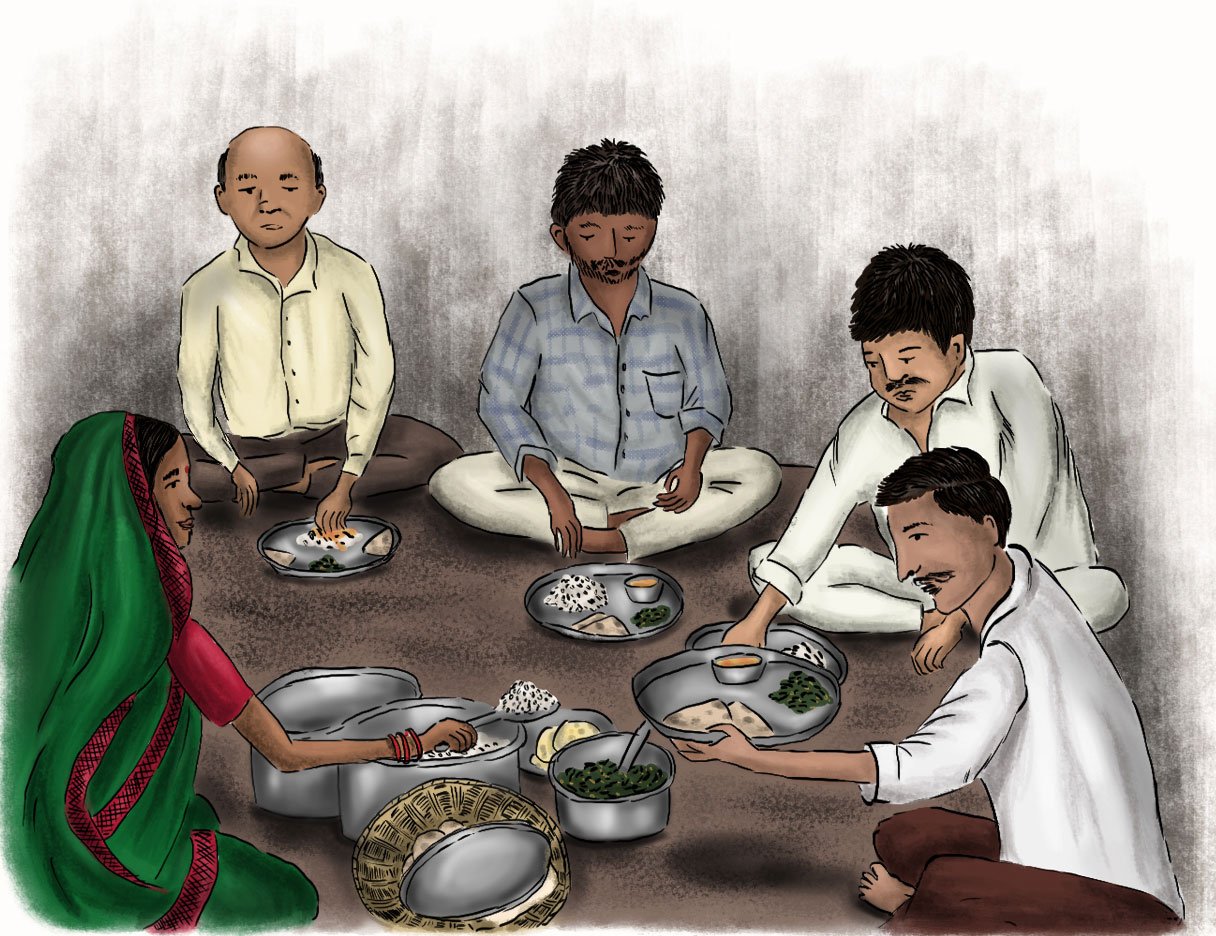

In the third verse, the singer-narrator spots what seems like a novelty to her, and observes a practice that’s contrary to tradition. The taps seen in Mumbai’s lanes get her attention. She realises that a woman here does not have to draw water from a well, or walk long distances to fetch it from a river, as the narrator would have to in her village. In the second line, she says that a woman running a

khanaval

, or food mess, charges even her own brother for a meal – which wasn’t the norm at home. The commercial nature of dealings in Mumbai is revealed here.

Left: Workers in the cotton mills of 19-century Mumbai used to strain their arms a lot, leaving them bone-tired at the end of the day. Right: Migrants in the city preferred the affordable meals served at a khanaval, or food mess, usually run by a woman. Illustrations: Antara Raman

The singer says in the fourth couplet that she has walked all over Mumbai in search of her son, right up to the Kulabyachi Dandi (‘Colaba’s tip’) “on the left side”. It is a reference to the city’s old British quarter, Colaba, and the part of it that forms the southernmost tip of Mumbai.

In the following three couplets, Jai Sakhale sings about a woman’s migration to Mumbai. Although she could not afford oil for her hair in the village, her life has changed after going to the city. She no longer sits on the floor like she used to in her village home. But the woman misses her village, and instead of eating fish like many do in Mumbai, when she returns home she looks for

kurdu,

a leafy vegetable, in the fields. She is excited and dresses well when she leaves her village to go to Mumbai. But barely halfway there, while travelling through the scenic Khandala

ghat

, her mind starts to wander. She anticipates the difficult times ahead and remembers her parents – for they will not be with her in the city.

In the last two ovi , the singer gives voice to a mother’s feelings for her young son working in Mumbai – possibly in a cotton mill. Money doesn’t grow on trees, she says, and her son works so hard every day that his bones are wrung out of all energy. Even after days upon days of hard work, he earns very little. But, she says, her son’s labour and sweat is worth a lakh of rupees.

अशी साहेबाची बोली बाळायानाला आली

माझ्याई बाळान् ला अन् खुडची बसायाला दिली

मुंबई ग शहरामधी गलोगलीनी गलास

माझ्याई बाळाचा कुठ करु मी तलाश

मुंबई शहरामधी गलोगलीनी नळ

सख्या भावापाशी बहिण घेती खानावळ

मुंबई मुंबई बाई सर्वी हिंडूनी पाहिली

कुलाब्याची दांडी डाव्या बाजूला राहीली

नार गेली मुंबईला नार बसना भोईला

आपल्या देशाला ग बाई त्याल मिळना डोईला

नार निघाली मुंबईला नार खाई ना म्हावर

आपल्या देशाला हिंड कुर्डची वावर

नार निघाली मुंबईला नार लई नटयली

खंडाळ्याच्या घाटामधी आई बाप आठवली

मुंबई ग शहरामधी नाही पैसा झाडाला

माझ्याई बाळाच्या पिळ पडला हाडाला

मुंबई शहरामधी नाही पैसा फुकाचा

माझ्याई बाळाच्या बाई घाम गळतो लाखाचा

aśī sāhēbācī bōlī bāḷāyānālā ālī

mājhyāī bāḷān lā an khuḍacī basāyālā dilī

mumbaī ga śaharāmadhī galōgalīnī galāsa

mājhyāī bāḷācā kuṭha karu mī tapāsa

mumbaī śaharāmadhī galōgalīnī naḷa

sakhyā bhāvāpāśī bahiṇa ghētī khānāvaḷa

mumbaī mumbaī bāī sarvī hiṇḍūnī pāhilī

kulābyācī dāṇḍī ḍāvyā bājūlā rāhīlī

nāra gēlī mumbaīlā nāra basanā bhōīlā

āpalyā dēśālā ga bāī tyāla miḷanā ḍōīlā

nāra nighālī mumbaīlā nāra khāīnā mhāvara

āpalyā dēśālā hiṇḍa kurḍacī vāvara

nāra nighālī mumbaīlā nāra laī naṭayalī

khaṇḍāḷyācyā ghāṭāmadhī āī bāpa āṭhavalī

mumbaī ga śaharāmadhī nāhī paisā jhāḍālā

mājhyāī bāḷācyā piḷa paḍalā hāḍālā

mumbaī śaharāmadhī nāhī paisā phukācā

mājhyāī bāḷācyā bāī ghāma gaḷatō lākhācā

My son can speak English, the

sahebs

’ language

They offered my son a chair to sit on

In Mumbai, the lanes are filled with glass [tumblers]

Where shall I find my son [in this crowd]

There are taps in every lane of Mumbai

A sister charges even her brother for meals

I have gone all over Mumbai and seen all of it

The Kulabyachi Dandi is on the left side

The woman who went to Mumbai, she no longer sits on the floor

Back in her village, she didn’t even have oil for her hair

The woman is leaving for Mumbai, she does not eat fish [there]

She returns to her village and looks for

kurdu

[a leafy vegetable] in the fields

The woman was all dressed up to go to Mumbai

At Khandala

ghat

, she remembered her mother and father

In Mumbai city, money doesn’t grow on trees

My son works hard, his bones are wrung out of energy

In Mumbai city, money doesn’t come for free

My son’s sweat is worth a lakh of rupees

Performer/ Singer:

Jai Sakhale

Village: Lavharde

Taluka: Mulshi

District: Pune

Caste: Nav Bauddha (Neo Buddhist)

Age: Died in 2012

Education: None

Children: 1 daughter (Lilabai Shinde – contributor to the Grindmill Songs Project)

Date: Her songs were recorded on October 5, 1999

Illustrator: Antara Raman is a recent graduate of Visual Communication from Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Bengaluru. Conceptual art and storytelling in all its forms are the biggest influences on her illustration and design practice.

Poster: Sinchita Maji

Read about the original Grindmill Songs Project founded by Hema Rairkar and Guy Poitevin.