When Bhanwari Devi’s 13 year-old daughter was raped in the bajra fields by an upper caste youth, she picked up a lathi and went after the rapist herself. She had no faith in the police and courts. Either way, she was prevented from seeking any redress by the dominant castes of Ahiron ka Rampura. “The village caste panchayat promised me justice,” she says. “Instead, they threw me and my family out of Rampura.” Nearly a decade after the rape, no one in this village in Ajmer district has been punished.

It doesn’t mean much, though, in Rajasthan . On average in this state, one Dalit woman is raped every 60 hours.

Data from reports of the National Commission for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes show that nearly 900 cases of sexual assault of SC women were registered with the police between 1991 and 1996. That’s round 150 cases a year – or one every 60 hours. (Barring a few months of President’s rule, the state was entirely in Bharatiya Janata Party control through this period.) The numbers don’t measure the reality. In this state, the extent of under-reporting of such crimes is perhaps the worst in the country.

In Naksoda of Dholpur district, the victim of one of the most dramatic atrocities has fled the village. In April 1998, Rameshwar Jatav, a Dalit, sought the return of Rs. 150 that he had loaned an upper caste Gujjar. That was asking for trouble. Enraged by his arrogance, a band of Gujjars pierced his nose and put a ring of two threads of jute, a metre long and 2 mm thick, through his nostrils. Then they paraded him around the village, leading him by the ring.

The incident hit the headlines and caused national outrage. It was widely reported overseas as well, both in print and on television. All that publicity, however, had no impact in ensuring justice. Terror within the village and a hostile bureaucracy at the ground level saw to that. And with the sensational and spectacular out of the way, the press lost interest in the case. So, apparently, did the human rights groups. The victims faced the post-media music on their own. Rameshwar completely changed his line in court. Yes, the atrocity had happened. However, it was not the six people named in his complaint who had done it. He could not identify the guilty.

The senior medical officer, who had recorded the injuries in detail, now pleaded forgetfulness. Yes, Rameshwar had approached him with those wounds. He could not remember, though, if the victim had told him how he had come by those unusual injuries.

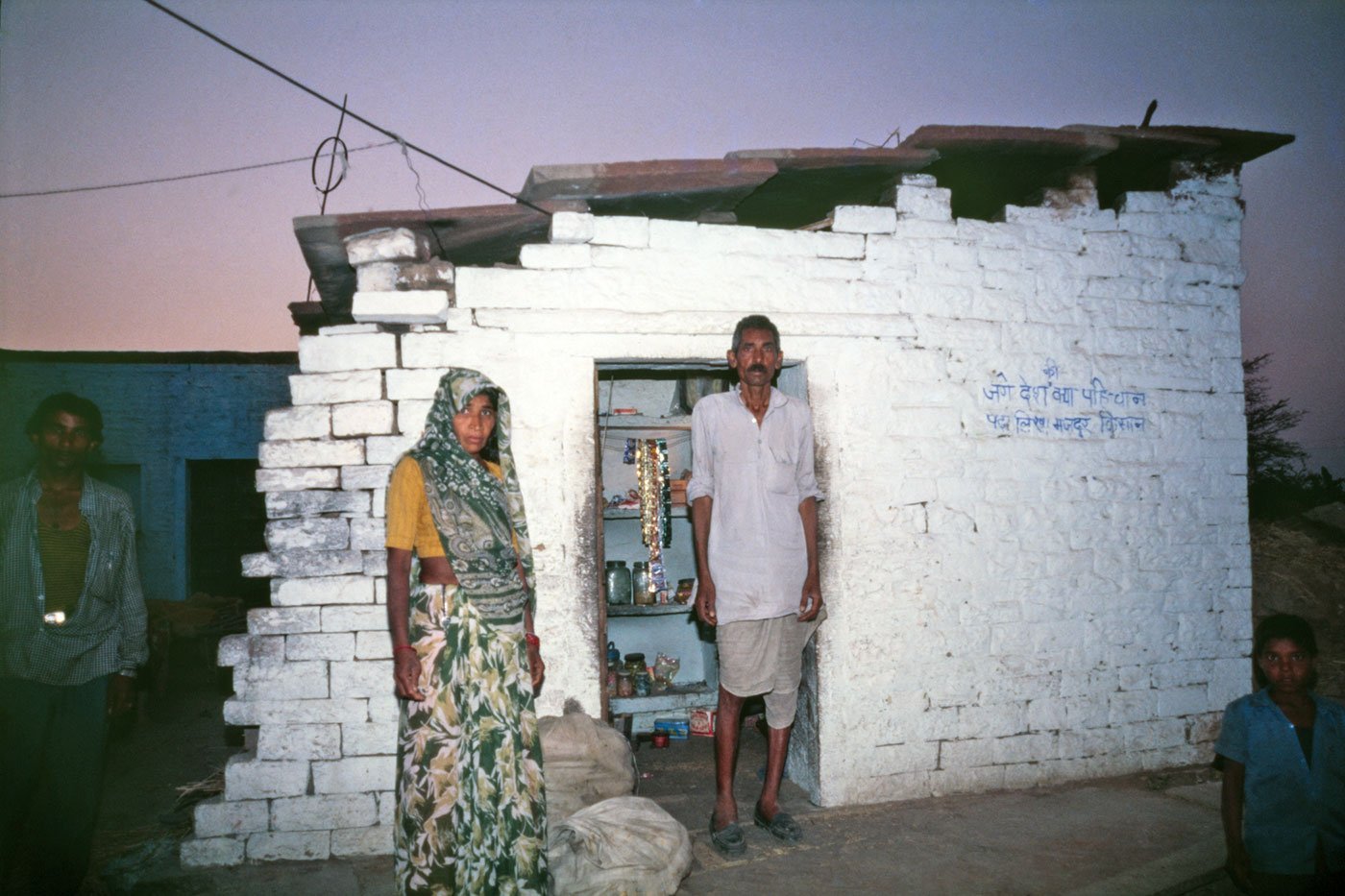

Rameshwar’s Jatav's parents at their home in Naksoda village, where Jatav was paraded with a jute ring in his nostril: 'We live here in terror'

Rameshwar’s father, Mangi Lal, has himself turned hostile as a witness. “What do you expect us to do?” he asked me in Naksoda. “We live here in terror. The authorities were totally against us. The Gujjars can finish us any time. Various powerful people, and some in the police, forced this on us.” Rameshwar has left the village. Mangi Lal has sold one of the just three bigha s of land the family owns to meet the costs of the case thus far.

For the world, it was a barbaric act. In Rajasthan, it just falls into one of thousands of 'Other IPC' (Indian Penal Code) cases. Which means cases other than murder, rape, arson or grievous hurt. Between 1991-96, there was one such case registered every four hours.

In Sainthri in Bharatpur district, residents say there have been no marriages for seven years. Not of the men, at least. That’s how its been since June 1992, when Sainthri was stormed by a rampaging upper caste mob. Six people were murdered and many houses destroyed. Some of those killed were burned alive when the bittora (store of dung and fuelwood) they were hiding in was deliberately set alight.

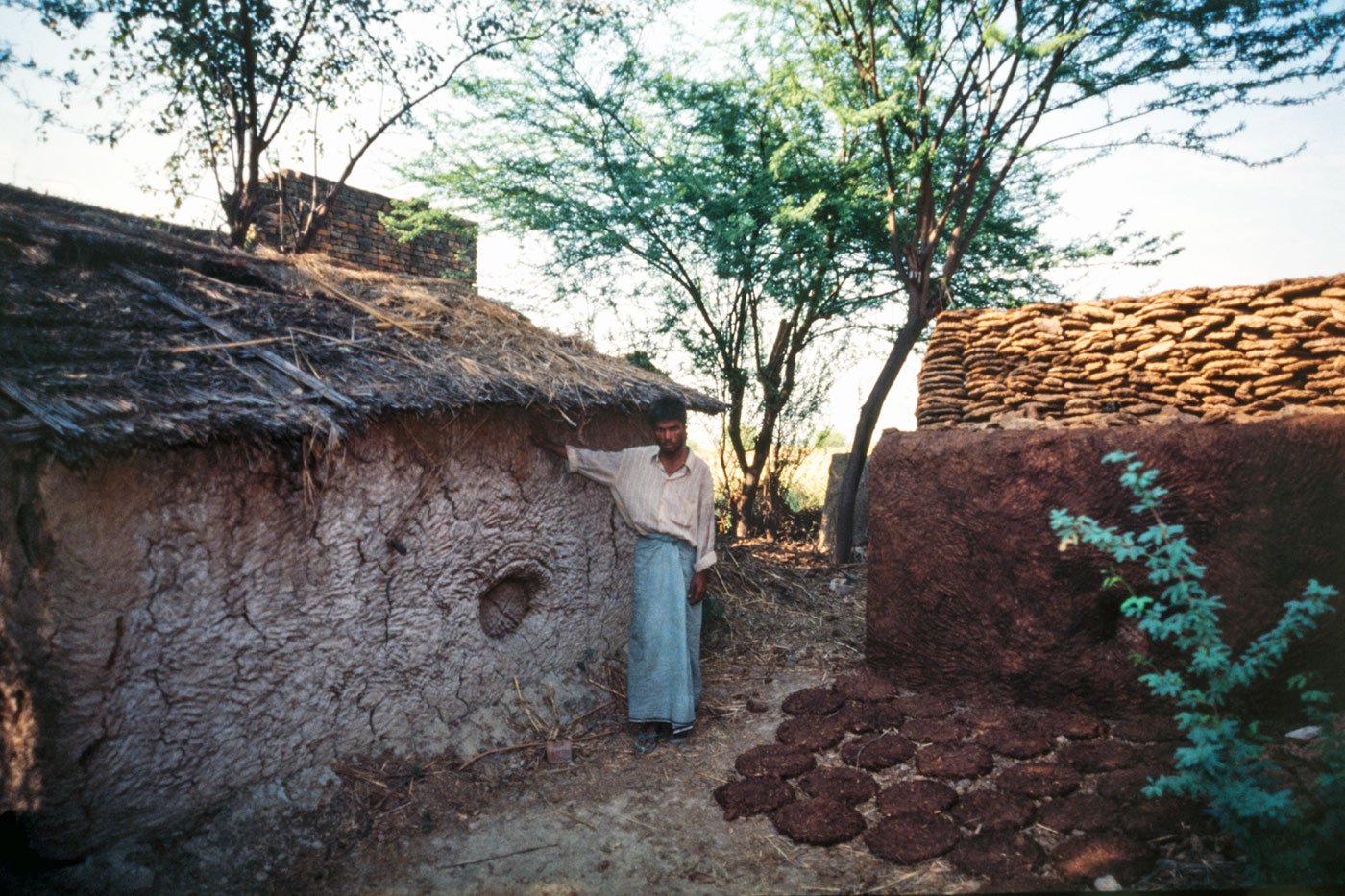

In Sainthri village, a similar dung and fuelwood bittora in a shed was stormed by a rampaging upper caste mob, killing six people

“The women of Sainthri are able to get married because they leave the village when they do so,” says Bhagwan Devi. “But not the men. Some men have left this village to get married. People don’t want to send their daughters here. They know that if we are attacked again, no one, neither police nor courts, will help us.”

Her cynicism is grounded in reality. Seven years after the murders, charges are yet to be framed in the matter.

That too, doesn’t mean much. One Dalit is murdered in this state a little over every nine days.

In the same village lives Tan Singh, a survivor of the bittora fire ( see cover image ). The medical record shows he suffered 35 per cent burns in that event. His ears have been more or less destroyed. The little compensation he got – because his brother was one of those killed – has long ago disappeared in medical expenses. “I had to sell my tiny plot of land to meet the costs,” says the devastated young man. That includes several hundreds of rupees each time on repeated trips to Jaipur – on just travel alone.

Tan Singh has become just a statistic . A Dalit is the victim of grievous hurt every 65 hours in this state.

In Raholi in

Tonk district, an attack on Dalits incited by local school teachers saw several

cases of arson. “The losses were very bad,” says Anju Phulwaria. She was the

elected

–

Dalit

–

sarpanch

, but, she says, “I was

suspended from the post on false charges.”

She’s not surprised that no one’s been punished for the act.

On average, one dalit house or property suffers an arson attack every five days in Rajasthan. In every category, the chances of the guilty being punished are very few.

Arun Kumar, the soft-spoken chief secretary, government of Rajasthan, disagrees with the idea of a structured bias against Dalits. He believes that the alarming numbers reflect the commitment of the state in registering such cases. “This is one of the few states where there is hardly any complaint about non-registration. Because we are diligent about it, there are more cases and thus high crime statistics.” He also believes the conviction rate in Rajasthan is better than in the rest of the country.

Anju Phulwaria was the elected Dalit sarpanch of Raholi but, she says, 'I was suspended from the post on false charges'

What do the figures say? Former Janata Dal Member of Parliament Than Singh was a member of a committee investigating crimes against Dalits in the early '90s. “The conviction rate was around three per cent,” he told me at his Jaipur residence.

In Dholpur district, where I visited the courts, I found it to be even less. In all, 359 such cases were committed to Sessions between 1996 and 1998. Some had been transferred to other courts or were pending. But the conviction rate here was under 2.5 per cent.

A senior police officer in Dholpur told me: “My only regret is that the courts are burdened with so many false issues. Well over 50 per cent of SC /ST complaints are false. People are put to needless harassment by such cases.”

His is a widely held view among the largely upper caste police officers of Rajasthan. (A senior government official refers to the force as the CRP – the “Charang-Rajput Police.” These two powerful castes dominated the force right up to the '90s.)

The idea that ordinary people, particularly the poor and weak, are liars is deep-rooted in the police. Take rape cases across all communities. The national average of such cases found to be false after investigation is around five per cent of the total. In Rajasthan, rape cases declared “false” average around 27 per cent.

This is like saying that women in the state tend to lie five times more than women in the rest of the country. The more likely explanation? A huge bias against women is deeply embedded in the system. The ‘false rape’ data covers all communities. But a detailed survey would likely establish that Dalits and Adivasis are the worst victims of that bias. Simply: the level of atrocities they suffer is far higher than other communities.

I had been assured everywhere I went in Rajasthan that Dalits were grossly misusing the law in general and the provisions of the SC and ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, in particular. Above all, the much feared Section 3 of the Act under which those guilty of casteist offences against Dalits and Adivasis can be imprisoned for up to five years along with a fine.

In reality, I could not find a single case where such serious punishment had been meted out to offenders.

In Dholpur itself, the few punishments handed out in cases generally involving offences against Dalits seemed unlikely to deter the guilty. They ranged from fines of Rs.100 or Rs. 250 or Rs. 500 to one month’s simple imprisonment. The most severe punishment I came across was six months simple imprisonment. In one case, the guilty had been put on “probation” with bail. The concept of probation is one this reporter had never run into in such cases anywhere else.

Dholpur’s is not an isolated instance. At the SC / ST Special Court in Tonk district headquarters, we learned that the conviction rate was just under two per cent.

So much for the numbers. What are the steps and the barriers, the process and the perils facing a dalit going to court? That’s another story.

This two-part story was originally published in The Hindu on June 13, 1999. It won the first Amnesty International Global Award for Human Rights Journalism, in the prize's inaugural year, 2000.