Eighty-two-year-old Bapu Sutar remembers that day in 1962 very clearly. He had just sold another of his wooden treadle handlooms. Seven feet tall and made by hand in his own workshop, it had fetched him a handsome 415 rupees from a weaver in Kolhapur’s Sangaon Kasaba village.

It would have been a happy memory if it wasn’t the last handloom he would ever make. The orders stopped coming after that; there were no more takers for his handmade wooden treadle looms. “ Tyaveli sagla modla [Everything came to an end then],” he recalls.

Today, six decades later, few in Rendal, in Maharashtra’s Kolhapur district, know that Bapu is the last remaining treadle loom maker in the village. Or that he was once a much sought-after craftsman. “All the other handloom makers of Rendal and nearby villages have died,” says Vasant Tambe, 85, the oldest weaver in the village.

Crafting handlooms out of wood itself is a tradition lost to Rendal. “Even that [last] handloom doesn’t exist,” Bapu says, struggling to be heard amidst the clanking of powerlooms in the workshops surrounding his modest home.

Bapu’s single-room traditional workshop, located within his home, has witnessed the passing of an era. The medley of browns in the workshop – dark, sepia, russet, saddle, sienna, mahogany, rufous and many more – are slowly fading, their lustre dimming with passing time.

Left : Bapu's workshop is replete with different tools of his trade, such as try squares (used to mark 90-degree angles on wood), wires, and motor rewinding instruments . Right: Among the array of traditional equipment and everyday objects at the workshop is a kerosene lamp from his childhood days

The humble workshop is almost a museum of the traditional craft of handmade wooden treadle looms, preserving the memories of a glorious chapter in Rendal's history

*****

Rendal is located 13 kilometres from Ichalkaranji, a textile town in Maharashtra’s Kolhapur district. In the early decades of the 20th century, several handlooms made their way to Ichalkaranji town, which went on to become one of the most renowned textile centres in the state and, eventually, in India. Rendal, given its proximity to Ichalkaranji, also became a smaller textile-manufacturing centre.

It was in 1928 that Bapu’s father, the late Krishna Sutar, first learned to make the giant looms weighing over 200 kilos. The late Date Dhulappa Sutar, a master craftsman from Ichalkaranji, taught Krishna how to make these looms, says Bapu.

“In the early 1930s there were three families in Ichalkaranji that made handlooms,” recalls Bapu, his memory as sharp as a finely woven thread. “Handlooms were proliferating at that time, so my father decided to learn how to make them.” His grandfather, the late Kallappa Sutar, used to make agricultural tools like sickle, spade and kulav (a type of plough), besides assembling the traditional moat (pulley system) for irrigation.

As a child, Bapu loved spending time at his father’s workshop. He made his first loom in 1954, at the age of 15. “Three of us worked on it for 72 hours, over six days,” he smiles. “We sold it for 115 rupees to a weaver in Rendal.” A princely sum, as a kilo of rice, he says, cost 50 paise back then.

By the early ’60s, the price of a handmade loom had risen to Rs. 415. “We made at least four handlooms in a month.” It was never sold as a single unit. “We carried the various parts on a bullock cart and assembled them in the weaver’s workshop,” he explains.

Soon, Bapu learned to make a dobby ( dabi in Marathi) – attached externally to the top of the loom, it helped make intricate designs and patterns on the cloth as it was being woven. It took him 30 hours over three days to make his first sagwan (teakwood) dabi . “I gave it for free to Lingappa Mahajan, a weaver in Rendal, to check if the quality was good,” he recalls.

Sometime in the 1950s, Bapu made his first teakwood ‘dabi’ (dobby) , a contraption that was used to create intricate patterns on cloth as it was being woven . He went on to make 800 dobbies within a decade

Bapu proudly shows off his collection of tools, a large part of which he inherited from his father, Krishna Sutar

Two craftsmen had to work two days to create a 10-kilo dobby that stood nearly a foot tall; Bapu made 800 such dabis in a decade. “A dabi sold for 18 rupees in the 1950s, increasing to 35 rupees by 1960s,” he says.

Towards the late 1950s, says Vasant, the weaver, Rendal had around 5,000 handlooms. “ Nauvari [nine-yard] sarees were made on these looms,” he says, recalling a time, in the ’60s when he would weave over 15 sarees a week.

The handlooms were predominantly made from sagwan . The dealers would bring the wood from Karnataka’s Dandeli town and sell it in Ichalkaranji. “Twice a month, we would take a bullock cart and bring it from Ichalkaranji [to Rendal],” says Bapu, adding the journey took them three hours each way.

Bapu would buy a ghanfoot (cubic feet) of sagwan for Rs. 7, which increased to Rs. 18 in the 1960s and stands at over Rs. 3000 today. Besides this, sali (iron bar), pattya (wooden plates), nut bolts and screws were also used. “Every handloom required roughly six kilos of iron and seven ghanfoot teak,” he says. In the 1940s, iron cost about 75 paise a kilo.

Bapu’s family sold their handlooms in the villages of Kolhapur’s Hatkanangle taluka and Karadaga, Koganoli, Boragaon villages in the bordering Chikodi taluka of Karnataka’s Belagavi district. The craft was so meticulous that only three artisans, Ramu Sutar, Bapu Baliso Sutar, and Krishna Sutar [all relatives], made handlooms in Rendal in the early 1940s.

Crafting handloom was a caste-based occupation performed mostly by members of the Sutar caste, listed as Other Backward Class in Maharashtra. “Only Panchal Sutar [sub-caste] used to make it,” says Bapu.

Bapu and his wife, Lalita, a homemaker, go down the memory lane at his workshop. The women of Rendal remember the handloom craft as a male-dominated space

A frame loom that was once used by Vasant Tambe, Rendal's oldest weaver and a contemporary of Bapu Sutar. During the Covid-19 lockdown, Vasant sold this handloom to raise money to make ends meet

It was also a male-dominated occupation. Bapu’s mother, the late Sonabai, was a farmer and a homemaker. His wife, Lalita Sutar, in her mid-60s, is a homemaker, too. “Women in Rendal would spin the thread on a charkha and wind it on a pirn. The men would then weave it,” says Vasant’s wife, Vimal, 77. According to the Fourth All-India Handloom Census (2019-20) , though, women make up 2,546,285 workers, or 72.3 per cent, of handloom workers in India.

To this day, Bapu remains in awe of the master artisans of the ’50s. “Kallappa Sutar from Kabnur village [Kolhapur district] would get loom orders from Hyderabad and Solapur. He [even] had nine labourers,” he says. For a time when only family members assisted with loom making, and barely anyone could afford hired help, Kallappa’s nine labourers were no mean achievement.

Bapu points towards a 2 x 2.5 feet sagwan box that he loves dearly and keeps locked in his workshop. “It has over 30 different types of spanners and other metallic tools. They may seem like normal tools to others, but for me they are a reminder of my art,” he says, visibly moved. Bapu and his elder brother, the late Vasant Sutar, inherited 90 spanners each from their father.

Two wooden racks, as old as Bapu, host an archive of chisel tools, hand planes, hand drills and braces, handsaws, vices and clamps, mortise chisel, try square, traditional metallic dividers and compass, marking gauge, marking knife, and more. “I inherited these tools from my grandfather and father,” he says proudly.

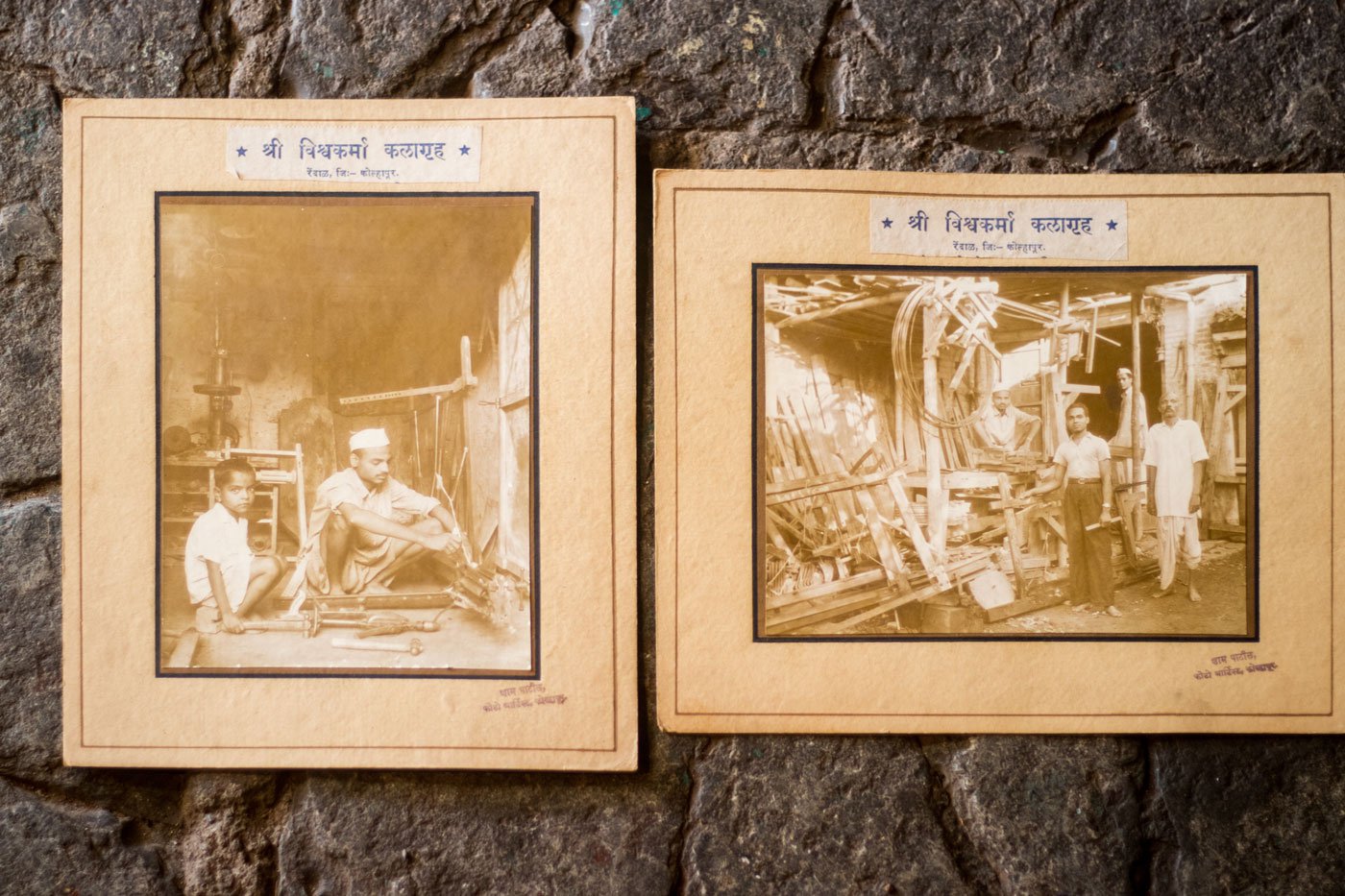

Bapu remembers the time when he would invite a photographer from Kolhapur — there were no photographers in Rendal in the 1950s – to help him preserve memories of his craft. Shyam Patil would charge him Rs 10 for six photographs and travel expenses. “Rendal has many photographers today, but none of the traditional artists are alive to be photographed,” he says.

Left: The pictures hung on the walls of Bapu's workshop date back to the 1950s when the Sutar family had a thriving handloom making business. Bapu is seen wearing a Nehru cap in both the photos . Right: Bapu and his elder brother, the late Vasant Sutar, inherited 90 spanners each from their father

Left: Bapu now earns a small income rewinding motors, for which he uses these wooden frames. Right: A traditional wooden switchboard that serves as a reminder of Bapu's carpentry days

*****

Bapu sold his last handloom in 1962. The years that followed were challenging – and not just for him.

Rendal itself witnessed massive changes during that decade. The demand for cotton sarees declined sharply, forcing weavers to start weaving shirting fabric. “The sarees we made were simple. With time, nothing changed in these sarees and, eventually, the demand fell,” says Vasant Tambe.

That’s not all. Powerlooms, with their promise of quicker production, higher profits, and ease of labour, started replacing handlooms. Almost all the handlooms in Rendal ceased to function . Today, only two weavers, 75-year-old Siraj Momin and 73-year-old Babulal Momin, use a handloom; they too are considering abandoning it soon.

“I loved making handlooms,” Bapu recalls joyfully, adding that he had made more than 400 frame looms in less than a decade. All by hand, with no written instructions to follow; neither he nor his father ever penned down the measurements or design for the looms. “ Mapa dokyat basleli. Tondpath jhala hota [All the designs were in my head. I knew all the measurements by heart],” he says.

Even as powerlooms took over the market, a few weavers who could not afford them started buying second-hand handlooms. During the ’70s, the price of used handlooms rose to as much as Rs. 800 apiece.

Bapu demonstrates how a manual hand drill was used; making wooden treadle handlooms by hand was an intense, laborious process

Left: The workshop is a treasure trove of traditional tools and implements. The randa , block plane (left), served multiple purposes, including smoothing and trimming end grain, while the favdi was used for drawing parallel lines. Right: Old models of a manual hand drill with a drill bit

“There was no one to make handlooms then. The prices of raw materials too increased, so the cost [of making handlooms] rose,” explains Bapu. “Also, several weavers sold their handlooms to weavers in Solapur district [another important textile centre].” With input and transport costs rising, making handlooms was no longer viable.

Bapu laughs when asked how much it would cost to make a handloom today. “Why would anyone want a handloom now?” he counters before making some calculations. “At least Rs. 50,000.”

Until the early 1960s, Bapu would augment his income from making looms by repairing handlooms, charging Rs. 5 for a visit. “Depending on the fault, we would increase the rates,” he remembers. Once the orders for new handlooms stopped coming, in the mid-1960s, Bapu and his brother, Vasant, started exploring other ways to make ends meet.

“We went to Kolhapur, where a mechanic friend taught us how to rewind and repair a motor in four days,” he says. They also learned how to repair powerlooms. Rewinding is an armature winding process done after the motor burns out. In the 1970s, Bapu would travel to the villages of Mangur, Jangamwadi and Boragaon in Karnataka’s Belagavi district and to Rangoli, Ichalkaranji and Hupari in Maharashtra’s Kolhapur district to rewind motors, submersible pumps and other machines. “Only my brother and I knew how to do this in Rendal, so we had a lot of work then.”

Some 60 years on, as work gets increasingly difficult to come by, a frail Bapu cycles to Ichalkaranji and to Rangoli village (5.2 km from Rendal) to repair motors. He takes at least two days to rewind one motor and earns around Rs. 5,000 a month. “I am not an ITI [Industrial Training Institute graduate],” he laughs, “but I can rewind the motors.”

Once a handloom maker of repute, Bapu now makes a living repairing and rewinding motors

Left: Bapu setting up the winding machine before rewinding it. Right: The 82-year-old's hands at work, holding a wire while rewinding a motor

He earns some additional money by cultivating sugarcane, jondhala (a variety of jowar), and bhuimug (groundnut) on his 22- guntha (0.5 acre) farmland. But given his advancing age, he is unable to work too hard on his farm. Frequent flooding also ensures that yield and revenue from his land remain modest.

The last two years have been particularly hard on Bapu, with the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdowns affecting work and income. “For several months, I didn’t get any orders,” he says. He also faces competition from the growing number of ITI graduates and mechanics in his village. Besides, “the motors manufactured now are of good quality and don’t require much rewinding.”

Things are not looking pretty in the handloom sector either. According to the Handloom Census 2019-20, Maharashtra was down to 3,509 handloom workers. In 1987-88 when the first Handloom Census was conducted, India had 67.39 lakh handloom workers. By 2019-2020, that figure fell to 35.22 lakh workers. India has been losing over 100,000 handloom workers every year.

Weavers remain grossly underpaid, with the Census finding that 94,201 of India’s 31.45 lakh handloom households are in debt. Handloom workers average 207 working days in a year.

The proliferation of powerlooms and the continued neglect of the handloom sector have badly hurt both hand weaving and loom crafting. Bapu is saddened by the state of affairs.

“No one wants to learn hand weaving. So how will the occupation survive?” he asks. “The government should start [handloom] training centres for younger students.” Unfortunately, no one in Rendal has learned the craft of making wooden handlooms from Bapu – at 82, he is the sole keeper of all knowledge related to a craft that stopped being practised six decades ago.

I ask him if, someday, he would like to make another handloom. “They [the handlooms] have fallen silent today, but the traditional wooden equipment and my hands still have life,” he says. He stares at the walnut brown wooden box and smiles wistfully, his gaze and his memories fading into the shades of brown.

Bapu's five-decade-old workshop carefully preserves woodworking and metallic tools that hark back to a time when Rendal was known for its handloom makers and weavers

Metallic tools, such as dividers and compasses, that Bapu once used to craft his sought-after treadle looms

Bapu stores the various materials used for his rewinding work in meticulously labelled plastic jars

Old dobbies and other handloom parts owned by Babalal Momin, one of Rendal's last two weavers to still use handloom, now lie in ruins near his house

At 82, Bapu is the sole keeper of all knowledge related to a craft that Rendal stopped practising six decades ago

This story is part of a series on rural artisans by Sanket Jain, and is supported by the Mrinalini Mukherjee Foundation.