India’s legislation: a parliamentary shift

FOCUS

The Indian government made significant legislative changes in the fiscal year 2023-24. This bulletin outlines key amendments made to laws, while foregrounding the nation’s constitutional values

The first Law Minister of India, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, would cast a skeptical eye on proceedings as they unfolded at the New Parliament House. After all, he was the one to say, “If I find the Constitution being misused, I shall be the first to burn it.”

The PARI Library takes a hard look at the important new Bills passed in Parliament in 2023 that threaten citizens’ constitutional rights.

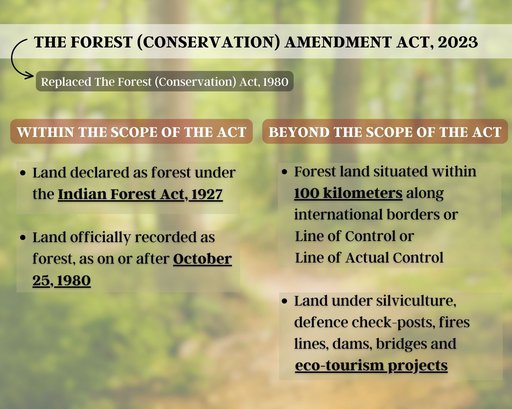

Take the case of the Forest (Conservation) Amendment Act, 2023. India’s forests are no longer inviolate if they lie near borders. Consider the example of the North East of India that shares international borders with multiple countries. The ‘unclassed forests’ of North East make up more than 50 per cent of recorded forest areas that can now, after the amendment, be taken up for military and other uses.

In the digital privacy space, a new law – the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha (Second) Sanhita Act – makes it easier for investigative agencies to seize digital devices like phones and laptops during an investigation – threatening citizens’ most basic right to privacy. Similarly the new Telecommunications Act prescribes using verifiable biometric based identification by an authorised entity of telecommunication services. The acquisition and storage of biometric records raises critical privacy and cybersecurity concerns.

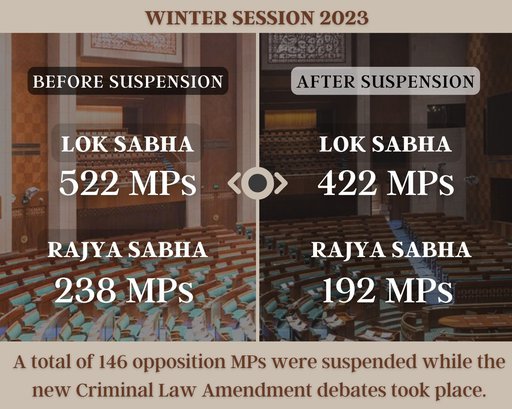

These new legislative measures were adopted in India’s parliamentary sessions in 2023. For the first time in Parliament’s 72-year-old history, a staggering 146 opposition Members of Parliament (MPs) were expelled in the Winter Session conducted in December 2023. This marks the highest number of suspensions in a single session.

With 46 members of the Rajya Sabha and 100 of the Lok Sabha suspended, the opposition benches looked empty when the Criminal Law amendment debate took place.

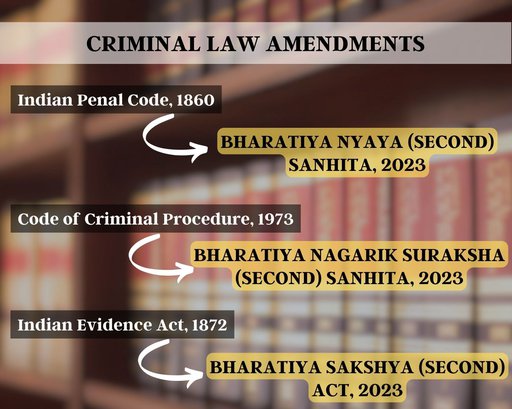

The debate introduced three bills in the Lok Sabha, with the objective of reformation and decolonisation of Indian criminal laws: the Indian Penal Code, 1860; the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973; and the Indian Evidence Act, 1872. Bharatiya Nyaya (Second) Sanhita, 2023 (BNS), Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha (Second) Sanhita, 2023 (BNSS), and Bharatiya Sakshya (Second) Bill, 2023 (BSB) respectively replaced these Principal Acts. Within 13 days these bills received Presidential assent on December 25, and will come into force on July 1, 2024.

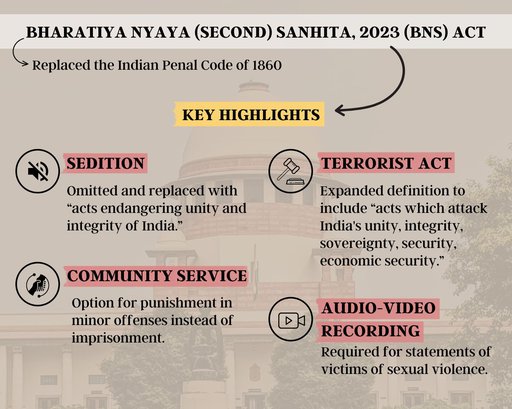

While the Bharatiya Nyaya (Second) Sanhita, 2023 (BNS) Act predominantly reconstructs existing provisions, notable amendments have been introduced through the second iteration of the BNS bill, breaking away from its predecessor, the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC).

This Act has retained the offense of sedition (now designated under a new nomenclature) while broadening the purview of what constitutes “acts endangering sovereignty, unity, and integrity of India.” The proposed Section 152 goes beyond the erstwhile criteria of “incitement to violence” or “disruption of public order” as provisos for invoking sedition charges. Instead, it criminalises any act that “excites or attempts to excite, secession or armed rebellion, or subversive activities.”

Another notable amendment in the second iteration of the BNS Act is the exclusion of Section 377 of the IPC: “Whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal, shall be punished with imprisonment for life [...].” However, the absence of necessary provisions in the new act leaves individuals of other genders without security against sexual assault.

The Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha (Second) Sanhita Act of 2023, referred to as the BNSS Act, supersedes the Criminal Procedure Code of 1973. This legislation mandates a significant departure by extending the permissible duration of police custody beyond the initial 15 days to a maximum of 90 days following arrest. The extended duration of detention applies specifically to severe offenses carrying penalties such as death, life imprisonment, or imprisonment for a minimum of 10 years.

Furthermore, the Act allows agencies to seize digital devices like phones and laptops during investigations which could potentially breach the right to privacy.

The Bharatiya Sakshya (Second) Act, 2023 by and large preserves the structure of the Indian Evidence Act of 1872 with minimal amendments.

The Forest (Conservation) Amendment Act, 2023 seeks to replace the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980. The amended Act exempts certain types of land under its provisions. These include:

“(a) such forest land situated alongside a rail line or a public road maintained by the Government, which provides access to a habitation, or to a rail, and roadside amenity up to a maximum size of 0.10 hectare in each case;

(b) such tree, tree plantation or reafforestation raised on lands that are not specified in clause (a) or clause (b) of sub-section (1); and

(c) such forest land:

(i) as is situated within a distance of one hundred kilometres along international borders or Line of Control or Line of Actual Control, as the case may be, proposed to be used for construction of strategic linear project of national importance and concerning national security; or

(ii) up to ten hectares, proposed to be used for construction of security related infrastructure; or

(iii) as is proposed to be used for construction of defence related project or a camp for paramilitary forces or public utility projects [...]."

Notably, this amendment does not weigh in on the ecological concerns of climate crisis and environment degradation.

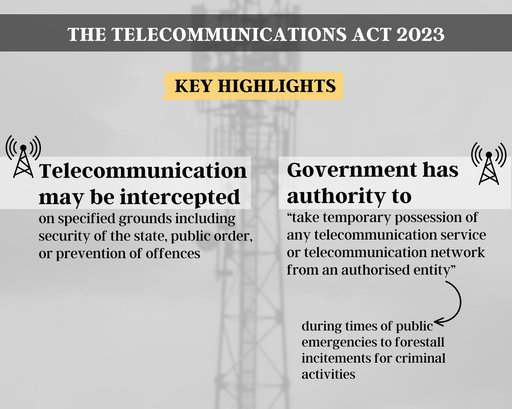

The Parliament also introduced some legislative measures bearing significant implications on India’s digital sector with the passing of the Telecommunications Act 2023, the Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023 (DPDP Act), and the Broadcasting Services (Regulation) Bill 2023. These measures, exerting direct influence on citizen’s digital rights and constitutionally protected privacy rights, control online content and deploy forcible shutdown of the telecommunication network as a regulatory tool.

With opposition voices absent, the Telecommunications Bill swiftly made it to the Presidential desk, securing assent on December 25, a mere four days after it was passed in the Lok Sabha. In its attempt to reform the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885 and the Indian Wireless Telegraphy Act, 1933, this Act upholds modernising regulatory frameworks such as:

“(a) [...] prior consent of users for receiving certain specified messages or class of specified messages;

(b) the preparation and maintenance of one or more registers, to be called as “Do Not Disturb” register, to ensure that users do not receive specified messages or class of specified messages without prior consent; or

(c) the mechanism to enable users to report any malware or specified messages received in contravention of this section.”

The Act also grants the government authority to “take temporary possession of any telecommunication service or telecommunication network from an authorised entity” during times of public emergencies to forestall incitements for criminal activities.

This provision endows officials with substantial powers to monitor and regulate communications across the telecom network in the name of upholding public safety.

These reforms in the original Acts are deemed to be ‘citizen-centric,’ as was declared by the nation’s Home Minister. Tribal communities of the North East – the citizens of our country – who live close to the ‘unclassed forests,’ could potentially lose their livelihoods, culture and history. Their rights won’t be protected under the new Forest Conservation (Amendment) Act.

The criminal law amendments impinge on the citizens’ digital rights as well as the constitutionally protected right of privacy. These Acts pose challenges in navigating the equilibrium between citizens’ rights and the criminal legal proceedings, warranting a careful consideration of the amendments.

The chief architect of the nation’s constitution would surely be interested in finding out what, according to the union government, constitutes ‘citizen-centric.’

Cover design: Swadesha Sharma

AUTHOR

PARI Library

COPYRIGHT

PARI Library

PUBLICATION DATE

15 ಏಪ್ರಿಲ್, 2024