“The apricots taste different now.”

“I remember having snow up to my knee.”

“We always had rain, but never this much damage. We are afraid.”

“It’s getting hotter earlier now.”

“We don’t know why it’s happening –and we are unprepared.”

“The glaciers have receded by at least a kilometre.”

“There is no doubt that climate change is happening.”

From the city of Leh to the villages of Nubra Valley and across generations and occupations these are voices desperate to be heard. The damage that the people here have seen over the past six years because of flash floods, mudslides, landslides and severe rains adds up to crores of rupees.

Gulam Mohammed, owner of Shayok Guesthouse, knows about the growing climate changes in his village, Turtuk, and in the neighbouring village of Chulungkha. He says: “The problem is that we were and still are unprepared for the changes that will come.”

Nubra is a high altitude cold desert with bitingly low temperatures, scanty rainfall and epic glaciers. Turtuk sits on a hilltop in this region, surrounded by mighty mountains and green fields along the grand Shayok river. Once a stopover on the ancient Silk Route, the village is 3,000 metres above sea level. It is 10 kilometres away from the Line of Control (LoC) between India and Pakistan, and an eight-hour drive north of Leh.

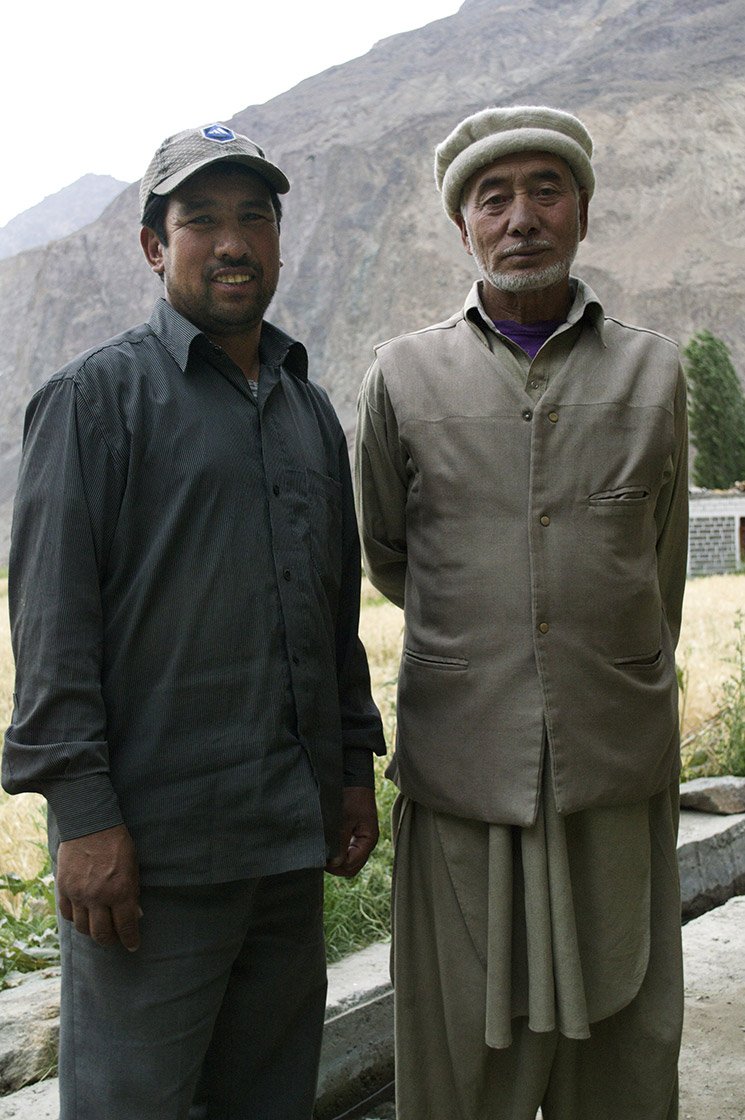

Gulam Mohammed (left) and Mohammed Ibrahim, the village headman

The area’s proximity to the LoC meant it was closed to tourism. This changed in 2010, after sustained lobbying by the locals – the same year, a sudden cloudburst caused widespread destruction in Leh, killing hundreds of people. Turtuk too received heavy rainfall that year, and has had unusual rain since then, which causes all kinds of damage. “We suffered during those rains,” says Mohammed Ibrahim, the village

goba

(headman). “Water seeped into homes and destroyed stored food, the rain ruined farmland. We sent reports to the government officials, but some people are still waiting for support.”

The old houses, built using seven layers of wood, stone, mud, brush, grass and clay were not designed for heavy rain. “Earlier, when people had tin roofs, it was to display wealth,” Gulam Mohammed says. “Now, you have to find a way of getting a tin sheet because you can’t afford the rain damaging your home, especially during drying [of apricots and other fruits] season.”

An old Balti roof with a new layer of tin sheet

According to Ibrahim Ashoor, an extension officer at the department of agriculture in a nearby town called Diskit, and one of the owners of Ashoor Guesthouse in Turtuk, there are other signs of change too: “Over the last 25 years, fruit has started ripening faster, and we are harvesting barley and buckwheat about 10 days earlier. The biggest problem is that we just don’t know how much it will rain or snow.”

“There is no doubt about climate change,” says Sonam Lotus, director of the India Meteorological Department in Srinagar, Kashmir. “There is an imbalance between nature and human activity. The small changes that policymakers are implementing are coming too late. We need bigger actions – from new laws on managing resources to conservation.”

Jayaraman Srinivasan of the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, and one of the authors of the periodic reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change confirms, “It is the rate of change that is concerning. Data shows that between 1973 and 2008, the temperature in Ladakh rose by three degrees Celsius, while in the rest of India it rose by only one degree. This is impacting the snow and rain cycles. When it rains in the desert – short but extreme spells – it is catastrophic; these places are not equipped to handle it.”

The Turtuk 'nala' is critical to the local ecology

Turtuk, ceded to India after the India-Pakistan war in 1971, is made up of three parts – Farol, Yul and Chutang. It is home to the Balti community whose territory – Baltistan – extends into Pakistan. Around 400 families live in Turtuk, according to Census 2011.

To conserve the fragile mountain environment, the Balti people have evolved intricate ecological systems such as canal water- sharing complete with a chunpa , or water watchman, whose job it is to ensure equal distribution of water. Every year the chunpa alternates the field that receives water first during sowing season. They have also evolved a food storage system, a cattle grazing schedule and milk sharing system, waste systems and even a polo team selection system!

Zakir Hussain, the 'chunpa' in Farol. Right: The canal system with dividers in each field

But the old ways are under siege. In recent years, along with shifts in the environment, there have been shifts in the economy and culture too. Zakir Hussain, the chunpa for Farol is worried about the future of Turtuk, “No one wants to farm anymore. Everyone wants a guesthouse. No one wants to raise cows and goats or take them grazing. If you go further up the mountains, you can see plastic clogging the streams. I didn’t want the chunpa position this year because it’s too much work. Over the last few years, because snowfall has lessened, there is less water in the beginning of March which is our sowing season, and it has caused fights among people.”

Ten more guesthouses are scheduled to come up in Turtuk by next year – at present there are around seven. For the community, tourism is an attempt to catalyse the local economy during the summer months, but the attendant cultural shifts are impacting the village. Now, as visitors go by, Balti children shout out greetings in English or Ladakhi, a sign that they will know a very different Turtuk than their parents (who speak the Balti language). But Kulsam Banu Bangchupa, a member of the panchyat , or local council, is adamant about building more guesthouses: “We don’t make money from our land. We need cash for illness or education, or our homes and other things.”

Gulam Mohammed adds, “We used to make everything here. But people don’t want to do that anymore. Our food comes from the public distribution system and our clothing is bought in Diskit.”

Kulsamji in her kitchen wearing a 'hamachanitu', the traditional Balti headgear of married women

Future tense

The elders in Turtuk know how much things have changed. “When we were young men going up into the mountains, the glaciers were much closer,” says Mohammed Ishupa, “They have receded at least a kilometre.” Another elder, Mohammed Ibrahim adds, “There is no snow now, so how can we have glaciers?”

Dr. Shakil Romshoo, glaciologist and head of the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Kashmir in Srinagar, says, “There has been a 20 per cent loss of glaciers in the last 60 years across the Indian Himalayan area. While there is not enough robust evidence about our glaciers, the government is starting to realise how important mass balance is for the future of our water.”

A cross section of men from the Balti community. Extreme left: Ibrahim Ashoor. Seated (l to r): Abdul Kadir, Mohammed Ibrahim, Ali Mohamed. Standing (l to r): Abdul Kareem, Mohammed Hassan, Gulam Mohammed, Mohammed Ishupa

The locals are bitter that people in Leh have got help during calamities, but this small village in a corner of the world gets little attention. When sudden rainstorms caused landslides in 2014 and 2015, houses and fields were ruined, in villages like Bogdong, Chulungkha, Tiger and Sumur. The people in Chulungkha say that local officials have visited but they are still awaiting financial help.

In Diskit, Habibullah Girdawar of the state revenue department in Nubra, speaks of the extent of the loss. In 2014, the damage to people’s homes and farms in Nubra Valley amounted to about Rs 3 crores, and in 2015 it went up to Rs. 15 crore, he says. These losses are debilitating for small farmers and landowners in harsh climates where there are no other income options.

The landslide cut through the heart of their fields; the rubble was once all working farms

“I

have never seen damage like this,” said Zulika Bano, the

goba

of Tiger village. “Like a

patient who first gets sick is unsure about how to handle the pain, it’s the

same with our village. We don’t know what’s coming or why, or how to face it.

But we’ll have to come together as a community to handle it."

Walking through Turtuk, Gulam Mohammed points to places where the area is vulnerable, like the bridge that connects both sides of the village. If a landslide were to occur, it would block the water from the Turtuk nala and flood the entire village.

“We have faced these problems before, but we still don’t know what to do. Maybe it won’t get so bad in my lifetime, but who can say about later?”

This article was written as part of a media fellowship awarded to the author by the environment news website The Third Pole and Earth Journalism Network, a voluntary, international group of journalists.

Special thanks to Gulam Mohammed, the Ashoor family, and the communities in the Nubra Valley.