In Malia taluka of Junagadh district in Gujarat, a differently-abled woman was given the rights to her late father’s land, which an uncle was trying to usurp; a woman from a minority community got a share in her husband’s property after he forced her to leave the house, and she can now send their two children to school while the husband is on the run; another woman filed divorce proceedings against an adulterous husband and was assured of a monetary compensation, a house in Rajkot, and police protection.

These victories in a cluster of villages in Malia (also referred to as Maliya in some government records) have been won due to the efforts of a group of women to fight pervasive gender injustice. They have formed a Nyaya Samiti – a justice committee – to address cases of domestic violence and other vulnerabilities under a larger federation called the Maliya Mahila Manch. The Aga Khan Rural Support Programme was involved in its formation. Started in 2006, the Manch is a federation of 75 self-help groups consisting of 1,186 women from 56 villages. Its various committees include the Nyaya Samiti, a Swasth Samiti, a Sikhshan Samiti and a Vayvati Samiti – working on issues of justice, health, education, law and liaison with the government.

From left to right: Hamilben Lakha, Hiraben Parmar, Prabhaben Khaniya (a member of the Manch who is not on the Nyaya Samiti) and Kanchanben Khanpara

The Nyaya Samiti has five members from different social and caste segments – Hiraben Parmar, Halimben Lakha, Geetaben Nemavat, Kanchanben Khanpara and Jayaben Khorasa. All the women, in their 40 and 50s, were part of the self-help groups for about five years before the federation collectively selected them as committee members.

When the Samiti came together, its members were given information about judicial proceedings by a government legal advisor at the Junagadh district court. Thus equipped, they began handling complaints and cases. This they do in part by sending legal notices to the accused. Two members, Hiraben and Kanchanben, have some education, and draft the notices on the Manch’s letterhead. Over time, by handling several cases, all five have become familiar with the relevant laws, and the lawyer- advisor also pitches in sometimes.

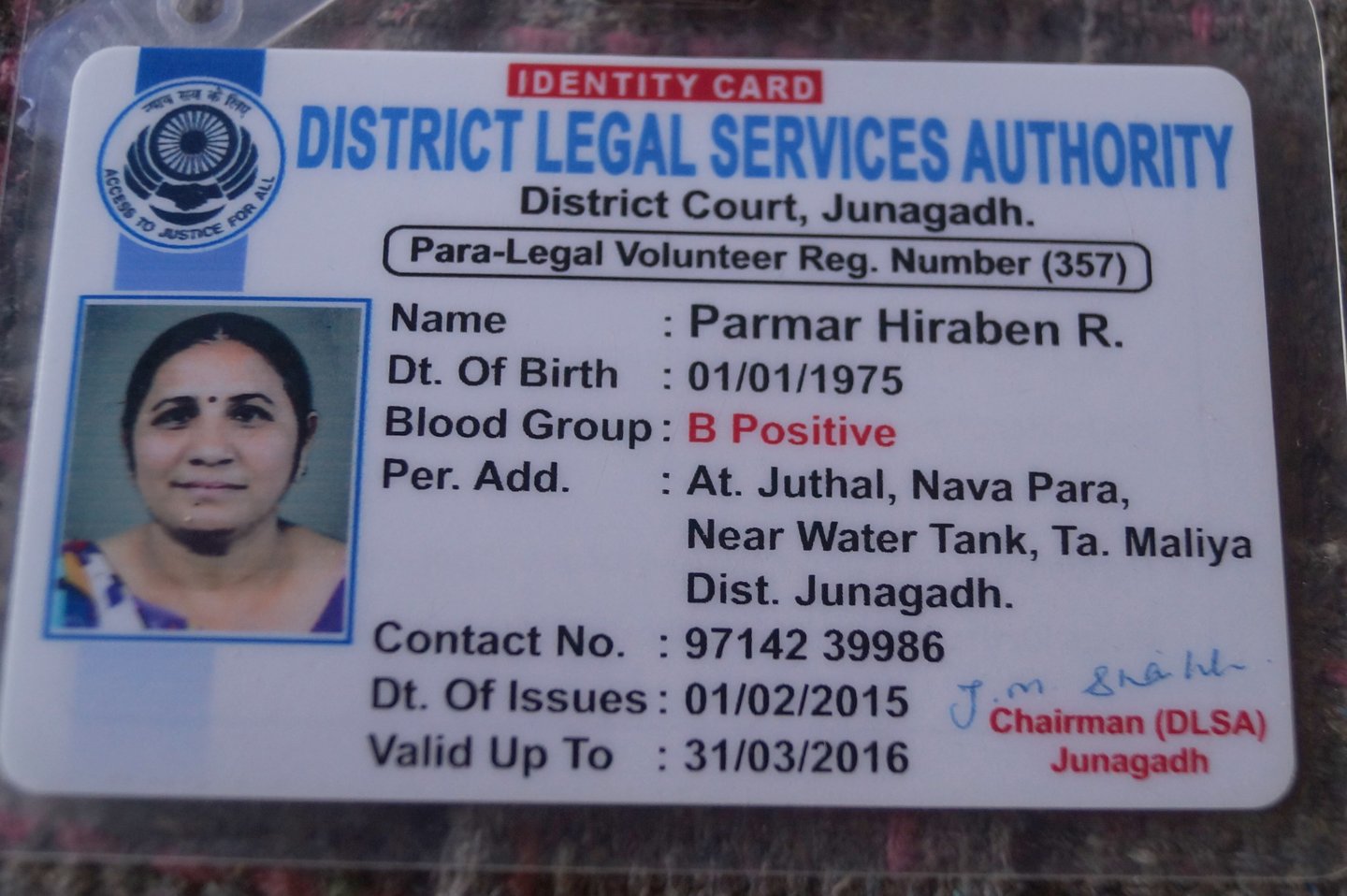

This card, as well as other forms of recognition, help membes of the Nyaya Samiti in their work

The verdicts are processed and delivered in a village ‘court’ on the 14th of every month. The court is a site given to them by the gram panchayat in Bhanduri village.

“A victim can file a case by giving 25 rupees as processing fee,” Hiraben says. “We send a notice to the accused and give a tentative date for the proceedings. We have faced a lot of problems [including] death threats. But when you try to do something good then courage follows automatically.”

The committee listens to both sides and gives a verdict that can be acceptable to both. They have no official status and their methods are based on persuasion, mediation and taking the discussion to the larger community – sometimes, these discussions stretch across an entire day or even more than a day.

If, as has often happened, an accused resists the ‘judgement’, the committee has to enforce it with the support of the police or refer the case to the district court. If a case is successfully resolved, the ‘client’ pays Rs. 500 to the Samiti as processing fee. The client also pays for expenses such as travel to the police station or the court. The Rs. 500 goes to the Samiti’s account and covers minor expenses or the costs of those complainants who cannot afford to pay anything.

Various stories speak of the remarkable ability of the Samiti to fight for justice. “In one of our cases, a husband [a well-off construction contractor] was cheating on his wife,” Hamilben recalls. “On being questioned about his infidelity, he started beating his wife frequently, and left her and their two children to fend for themselves.” A previous client persuaded the woman to seek help from the Nyaya Samiti. She was initially afraid to do so, fearful that it might escalate the beating – but then she came to the Samiti.

A summons was sent to the man. He refused to show up and instead targeted the Samiti members. “He would come with his goons to our office and threaten us, and pelt stones at our houses during the night. We were initially scared, but the police supported us,” Hiraben says.

The determined Samiti women persisted with the case and sent three more summons. When the man still did not turn up, they again approached the police and he was compelled to appear for the judicial proceedings.

The Samiti tries to take an unprejudiced view. Both sides are given the space to come together and speak. After the hearing, each side is given different options to consider, especially regarding their children. In the case of the contractor, after detailed discussions, the Samiti asked him to give one of his houses in Rajkot and Rs. 2.5 lakhs to his wife after they were divorced.

But it is often difficult for the Samiti to ensure compliance. Hiraben says, “In this same case, we took the woman to her house in Rajkot, broke open the lock that her husband had put on it and informed him. The man arrived in the village that night and mercilessly beat his wife. She managed to escape with the children and called me. I requested the sub-inspector of Rajkot to intervene.”

Working on such issues has been an uphill journey for the women on the Samiti. They have had to overcome resistance even from their own families. Their years of self-help group work, which included bringing government schemes to the village, gave them an initial boost and credibility. And over time, their success in settling disputes, in reconciling families or resolving other problems, has given them wider credibility and acceptance.

Hiraben Parmar (right) says: 'Isn’t this a form of empowerment – to speak up against what is wrong?'

Hiraben belongs to a socially-backward caste and lives on the village’s periphery, but her work on the Samiti has earned her respect and repute in her own community as well as among other villagers. “The cases we resolve act as moral support to other victims of violence. Our clients persuade other women and give them the courage to stand up against the tyranny of a male-dominated society. Isn’t this a form of empowerment – to speak up against what is wrong?” she asks, with pride.

The Samiti has resolved 32 cases so far. Such has been the success that families that have migrated to Rajkot, Una, Jamnagar and even Pune are now approaching the Samiti. The district court is supportive; in one instance, the judge, Hiraben recalls, admonished the appellant and said, “Why would you want to waste your money here? Go see the federation [the Maliya Mahila Manch].” It says a lot about these extraordinary women and their efforts.