The sling on his fractured arm was bothering Narayan Gaikwad. He took it off, adjusted his cap and looked for his blue diary and pen. He was in a hurry.

“ Majha naav Narayan Gaikwad. Mi Kolhapuratana aaloy. Tumhi kuthun aalay? [My name is Narayan Gaikwad. I have come from Kolhapur. Where have you come from?],” asked the 73-year-old farmer from Kolhapur’s Jambhali village.

He addressed his question to a group of Adivasi cultivators from Ahmadnagar district, who were taking shelter from the sun in a tent at Azad Maidan in south Mumbai. They were all among the farmers from 21 districts of Maharashtra gathered there on January 24-26 to protest against the new farm laws. Narayan had travelled with his injured hand for nearly 400 kilometres from his village in Shirol taluka , where he owns three acres of land.

After introducing himself, Narayan began talking about the problems he and others are facing in their village. “I am a farmer and I can relate to the issues,” he told me when we met on January 25. He was making notes in Marathi, with his fractured right arm. Even though his movements were causing him pain, he said, “It’s important to understand the struggles of farmers and agricultural labourers and so I listen to their problems.”

Later, he told me that he had spoken to more than 20 farmers from 10 districts at Azad Maidan.

Narayan’s arm was injured in the first week of January when a coconut frond fell on him while he was working on his farm. He cultivates sugarcane and

jowar

. He also grows vegetables without using chemical fertilisers. He ignored his injury at first, but when the pain didn’t reduce even after a week he went to a private doctor in Jambhali. “The doctor examined it and said it was a sprain. He asked me to tie a

patti

[crepe bandage],” he said.

Left: Farmers at the sit-in protest in Mumbai’s Azad Maidan. Right: Narayan (wearing a cap) and others from Shirol taluka at a protest rally in Ichalkaranji town

The pain persisted, however, and after seven more days Narayan went to the primary health centre (PHC) in Shirol, about 12 kilometres away. There, he got an X-ray done. “The doctor told me, ‘What kind of a person are you? Your hand is fractured since more than a week, and you are roaming carefree’,” Narayan told me. The PHC didn’t have plaster casts, so the doctor referred him to the Civil Hospital in Sangli, 15 kilometres from Shirol, where a cast was applied on Narayan’s arm later that day.

When he was leaving home for Azad Maidan on January 24, his family tried to stop him. But his spirit wasn’t dampened. “I told them, if you stop me, I will not only go to Mumbai but won’t return.” He travelled wearing a sling to hold up his arm.

His wife, Kusum, 66, who also farms on their land, packed 13 bhakris and laal chutney (made of red chillies), and sugar and ghee with it, for Narayan’s journey. She knew he wouldn’t eat even half of it. “He always distributes food to the protestors,” she told me when I visited Jambhali after the Mumbai protest. In two days, he ate only two bhakris and gave the rest to four Adivasi women farmers. “We are not bourgeois. Farmers have marched from several remote villages, and the least I can do is help them with food,” said Narayan, a member of the All India Kisan Sabha, affiliated with the Communist Party of India (Marxist).

The sit-in protest in Mumbai from January 24-26 had been organised by the Samyukta Shetkari Kamgar Morcha for Maharashtra’s farmers to express their solidarity with lakhs of farmers protesting at Delhi’s borders since November 26.

The three laws that the farmers have been protesting against are The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020 ; The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020 ; and The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020 . They were first passed as ordinances on June 5, 2020, then introduced as farm bills in Parliament on September 14 and hastened into Acts by the present government on the 20th of that month.

The farmers see these laws as devastating to their livelihoods by expanding the space for large corporates to have even greater power over farmers and farming. The new laws also undermine the main forms of support to the cultivator, including the minimum support price (MSP), the agricultural produce marketing committees (APMC), state procurement and more. They have also been criticised as affecting every Indian as they disable the right to legal recourse of all citizens, undermining Article 32 of the Indian Constitution.

Narayan (left) has met hundreds of farmers at protests across India. "He always distributes food to the protestors," says Kusum Gaikwad (right)

At Azad Maidan, it wasn’t for the first time that Narayan was sitting down to understand other farmers’ concerns. “I always talk to fellow protestors to know more about their lives,” he said. Over the years, he has met hundreds of farmers at protests and meetings across India and many have become friends. He has been to Delhi, Samastipur in Bihar, Khammam in Telangana and Kanniyakumari in Tamil Nadu, besides attending protests in Mumbai, Nagpur, Beed and Aurangabad in Maharashtra.

After the new laws were passed in September 2020, he says he took part in 10 protests across Kolhapur district. In the last four months, Narayan has spoken to several farmers from villages in Kolhapur, like Jambhali, Nandani, Haroli, Arjunwad, Dharangutti, Shirdhon and Takavade. “Of the hundreds of farmers I have spoken to, none of them want this law. Why was there a need to make these laws?” he asked, with anger in his voice.

On December 8, 2020, when farmers and farm workers observed a one-day bandh (shut-down) across India, he was in Shirol taluka’s Kurundvad town. “We were denied permission to take out a rally, but the people from the town cooperated and supported the farmers. You will never see Kurundvad’s shops closed otherwise – never,” he said.

To meet the farmers of nearby villages and attend protests, Narayan would wake up at 4 a.m. and complete his work by 10, and then ride his motorcycle to the villages. He returned by 5 p.m. to shoo away birds trying to feast on his crops, he said.

On December 20, he went to Nashik, about 500 kilometres from Jambhali, to join the 2,000-strong contingent of farmers from different parts of Maharashtra, who then set out on a vehicle jatha (march) towards Delhi the next day. Narayan went up to the Madhya Pradesh border and turned back with some farmers who couldn't bear the cold or had to return to their farm. “The farmers in Delhi are so inspiring. They have united the whole country. I wanted to go to Delhi but couldn’t because of the winter and a bad backache,” he said.

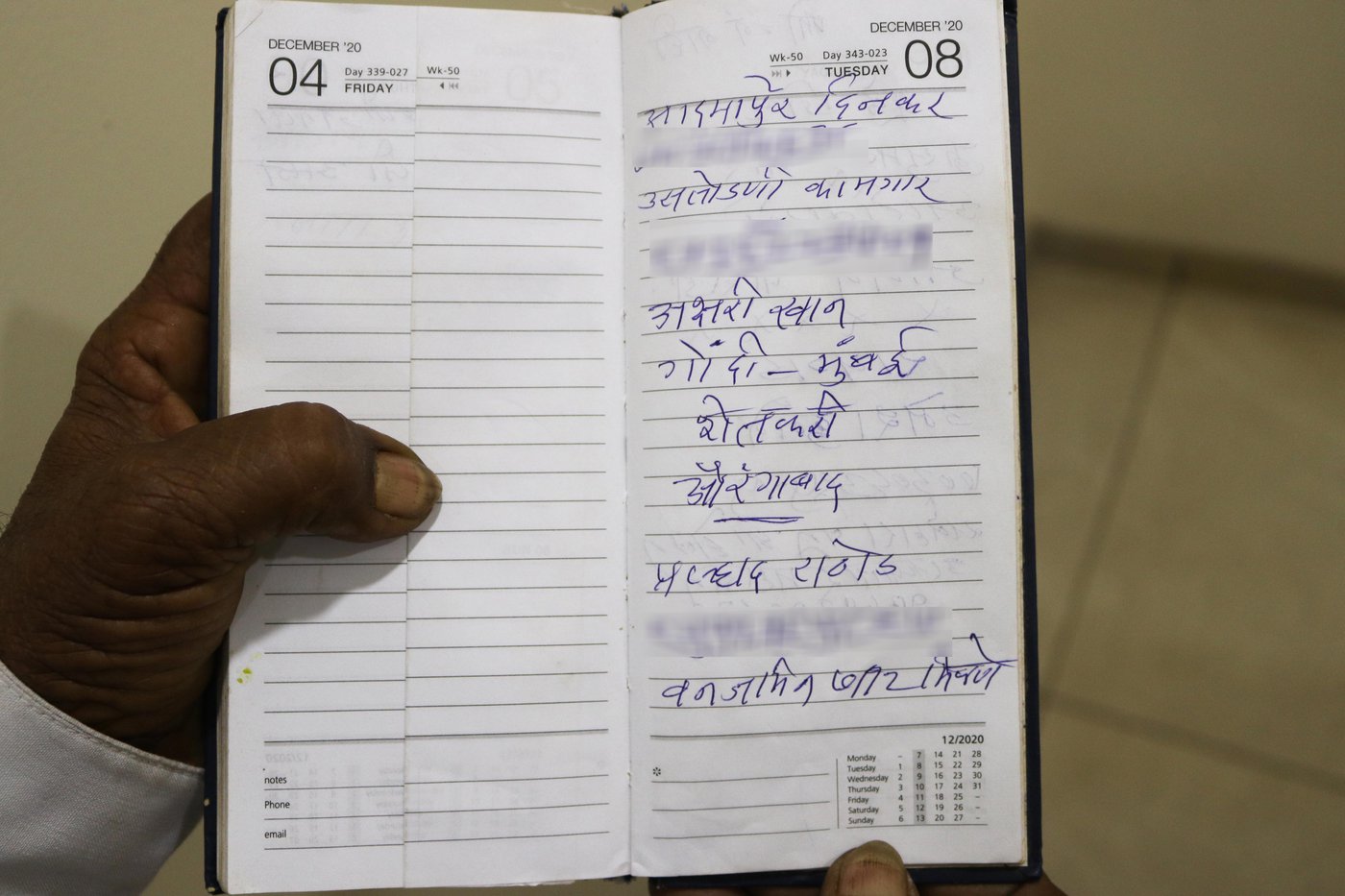

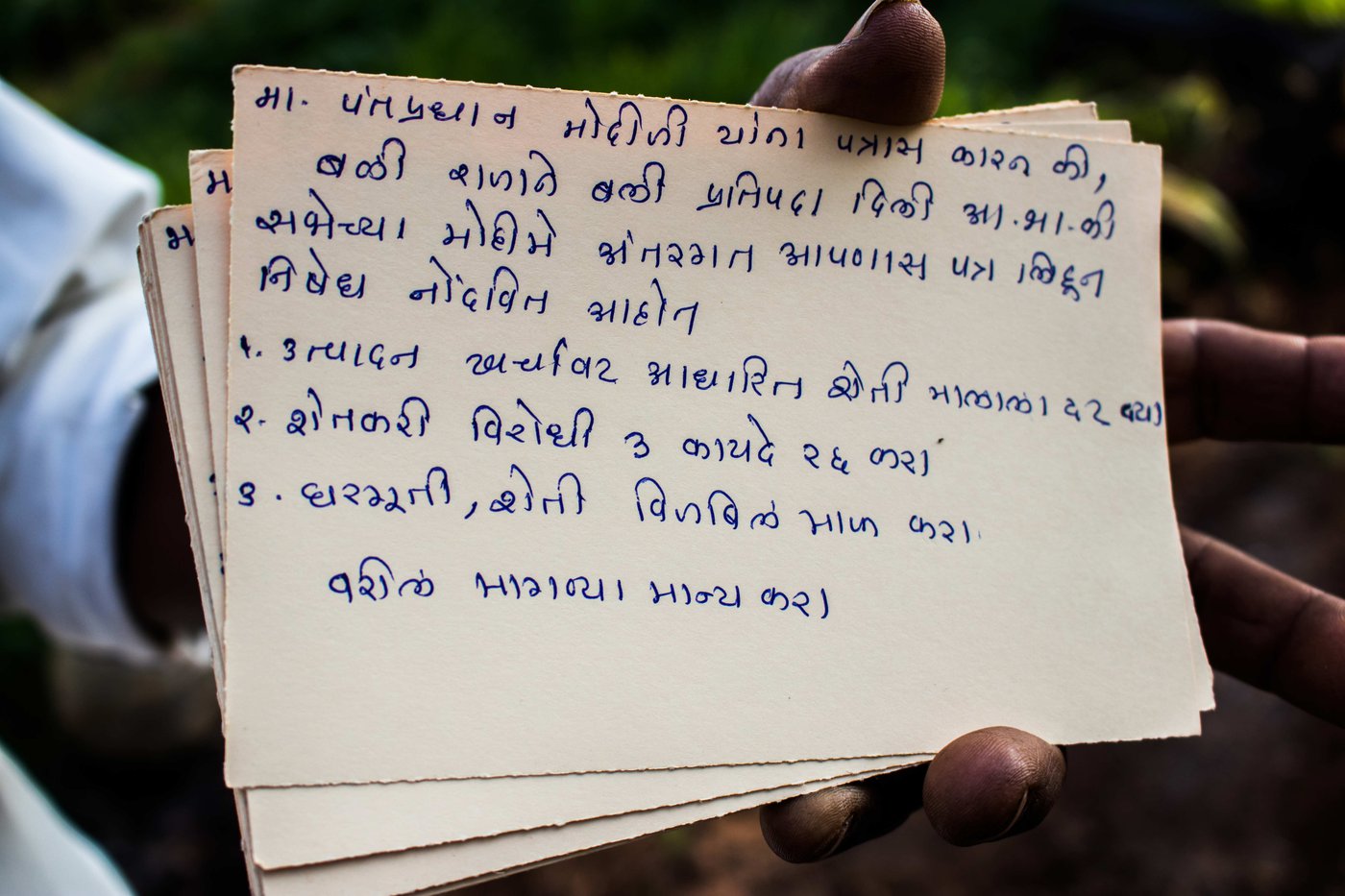

Narayan's diary (left) with his notes. He sent 250 postcards to the prime minister (right) asking him to repeal the new farm laws

Narayan has been protesting in other ways, too. Between September and October 2020, he wrote 250 postcards to Prime Minister Narendra Modi highlighting farmers’ concerns. He demanded a repeal of the three “black laws”, the implementation of the MSP as recommended by the Swaminathan Commission’s reports , and withdrawal of the Electricity Amendment Bill, 2020. He is wary after the central government’s failure to implement the Commission’s recommendations for MSP. “In 2015, the BJP government said in the Supreme Court that it wasn’t possible to implement MSP as per the Swaminathan Commission’s report. Now they say MSP won’t go away with these laws. How can we trust them?”

After him, many farmers from villages in his

taluka

started writing postcards to the prime minister, he told me. “People say farmers don’t understand these laws. We work in the field every day, how will we not understand?” he wondered.

Narayan has also been having discussions with activists and legal experts to develop a full understanding of the new laws and their effects. “These laws are dangerous for everyone. In case of a dispute, we can’t even go to the courts now,” he said.

He believes that non-farmers should also be made aware of the laws. “ Vichar prabhodan kela pahije purn deshat [The whole country must be awakened].”

On January 25, when farmers from Azad Maidan started marching towards the Governor of Maharashtra’s residence in south Mumbai, Narayan had stayed back to watch over the belongings of farmers from Kolhapur district.

In his notebook, he had compiled the list of the farmers’ concerns: ‘land titles, crop insurance, minimum support rice and APMC yards’. “The farm laws will first destroy the APMCs and then kill the Indian farmers,” he told me, adding, “These three laws will make us all labourers working for the corporates.”