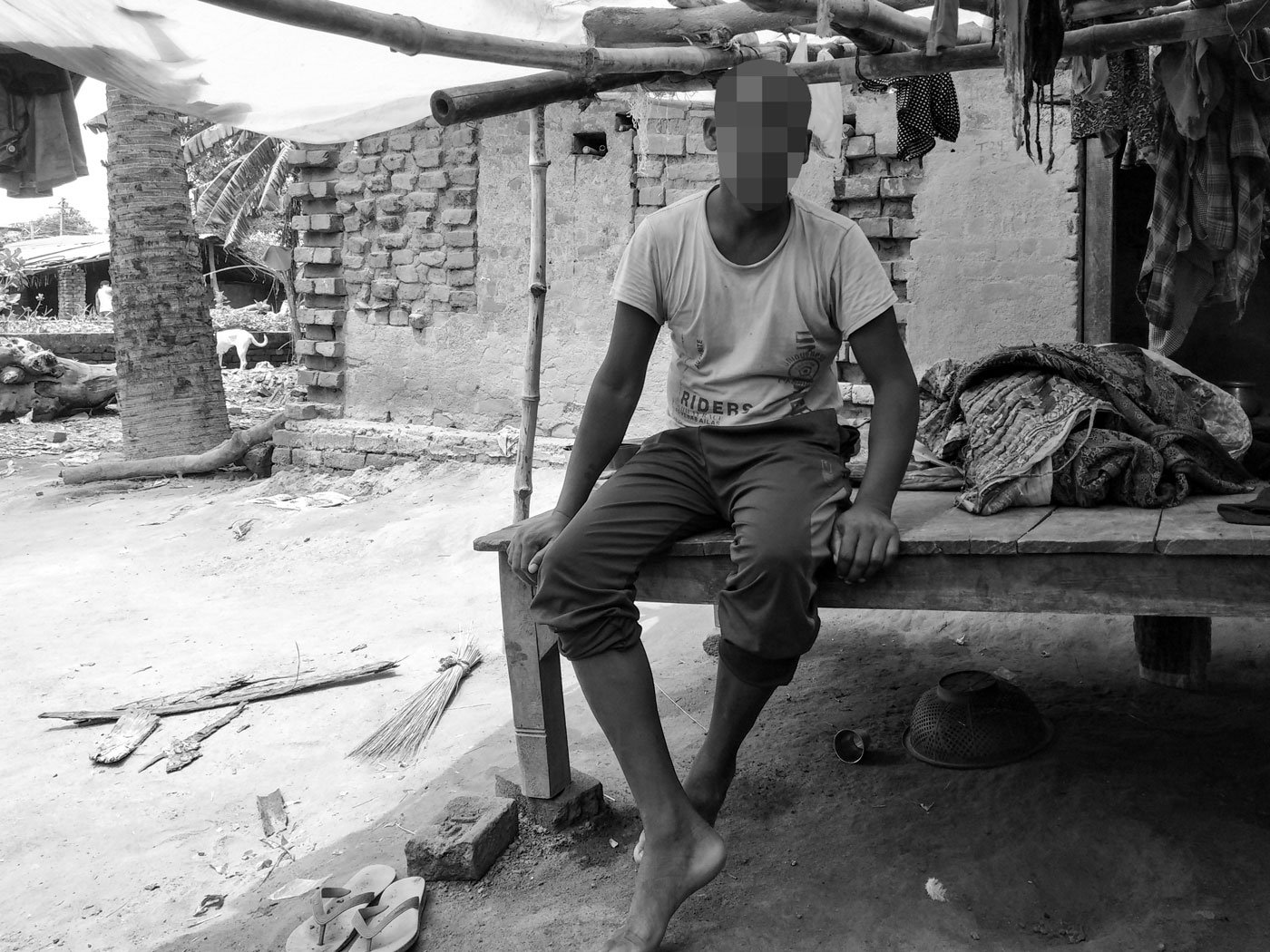

At 11 a.m. on a Monday morning, Muneshwar Manjhi, 41, is resting in the chowki outside his unplastered, dilapidated house. In that open space in front of the residence, a blue polythene sheet held up by bamboo poles shelters him from the sun. But it hardly provides any relief from the humidity. “I have had no work for the last 15 days,” says Muneshwar, who lives in a Musahari tola near Kako town, about 50 kilometres from Patna city.

The Musahari tola – a term used to mark the area where persons who belong to Musahar, a Dalit community, reside – is home to 60 families. Muneshwar and others in his tola depend on the daily wages they earn from working in the agricultural fields nearby. But the work is not regular, says Muneshwar. It is available only for 3-4 months of the year, during sowing and harvesting of the kharif and rabi crops.

The last time he had found work, it was on the farm of a ‘ babu sahib ’, a landowner, who belongs to the Rajput community. “For eight hours of work, we are paid 150 rupees in cash or 5 kilos of rice. That is all,” says Muneshwar about the daily wage that agricultural workers get. The rice in lieu of cash is paired with lunch – 4-5 rotis , or rice and dal , with a veg sabzi .

Though his grandfather had received three bigha (nearly two acres) of agricultural land in 1955 during the Bhoodan movement – when landlords gave up a part of their land for redistribution to landless persons – it is not of much use. “The land is three kilometres away from where we live. Whenever we sow crops, animals eat them and we incur loss,” explains Muneshwar.

Most days, Muneshwar’s family and others in the tola survive by brewing and selling m ahua daaru – liquor made from flowers of the mahua tree ( Madhuca longifolia var. latifolia ) .

This, though, is dangerous business. A stringent state law – Bihar Prohibition and Excise Act, 2016 – bans the manufacture, possession, sale or consumption of liquor or intoxicants. And even mahua daaru , defined as ‘country or traditional liquor’, falls within the law’s ambit.

Left: The unplastered, dipalidated house of Muneshwar Manjhi in the Musahari tola near Patna city. Right: Muneshwar in front of his house. He earns Rs 4,500 a month from selling mahua daaru , which is not enough for his basic needs. He says, ‘The sarkar has abandoned us ’

But a lack of alternative job opportunities forces Muneshwar to continue making the alcoholic spirit despite fear of raids, arrest and prosecution. “Who is not afraid? We do feel fear. But, when the police raids, we hide the liquor and flee,” he says. The police have raided the tola more than 10 times since the ban was enforced in October 2016. “I never got arrested. They have destroyed the utensils and chulha [earthen stove] many times, but we continue our work.”

Most of the Musahars are landless, and they are one of the most marginalised and stigmatised people in the country. Originally an indigenous forest tribe, the community's name is derived from two words – musa (rat) and ahar (food) – and means ‘those who eat rats’. In Bihar, the Musahars are categorised as a Scheduled Caste and listed as Mahadalit, among the most economically and socially disadvantaged Dalits. With low literacy rate – 29 per cent – and lack of skills, the population of more than 27 lakhs in the state is hardly engaged in any skilled labour. And though mahua daaru is a traditional beverage of the community, it is produced more for livelihood now.

Muneshwar has been making mahua daaru since he was 15 years old. “My father was poor. He pulled a thela [wooden hand cart used for ferrying goods]. The earnings were insufficient. I had to go to school on an empty stomach sometimes,” he says. “So I stopped going after a few months. Some of the families around were brewing liquor, so I started too. I have been doing this for 25 years.”

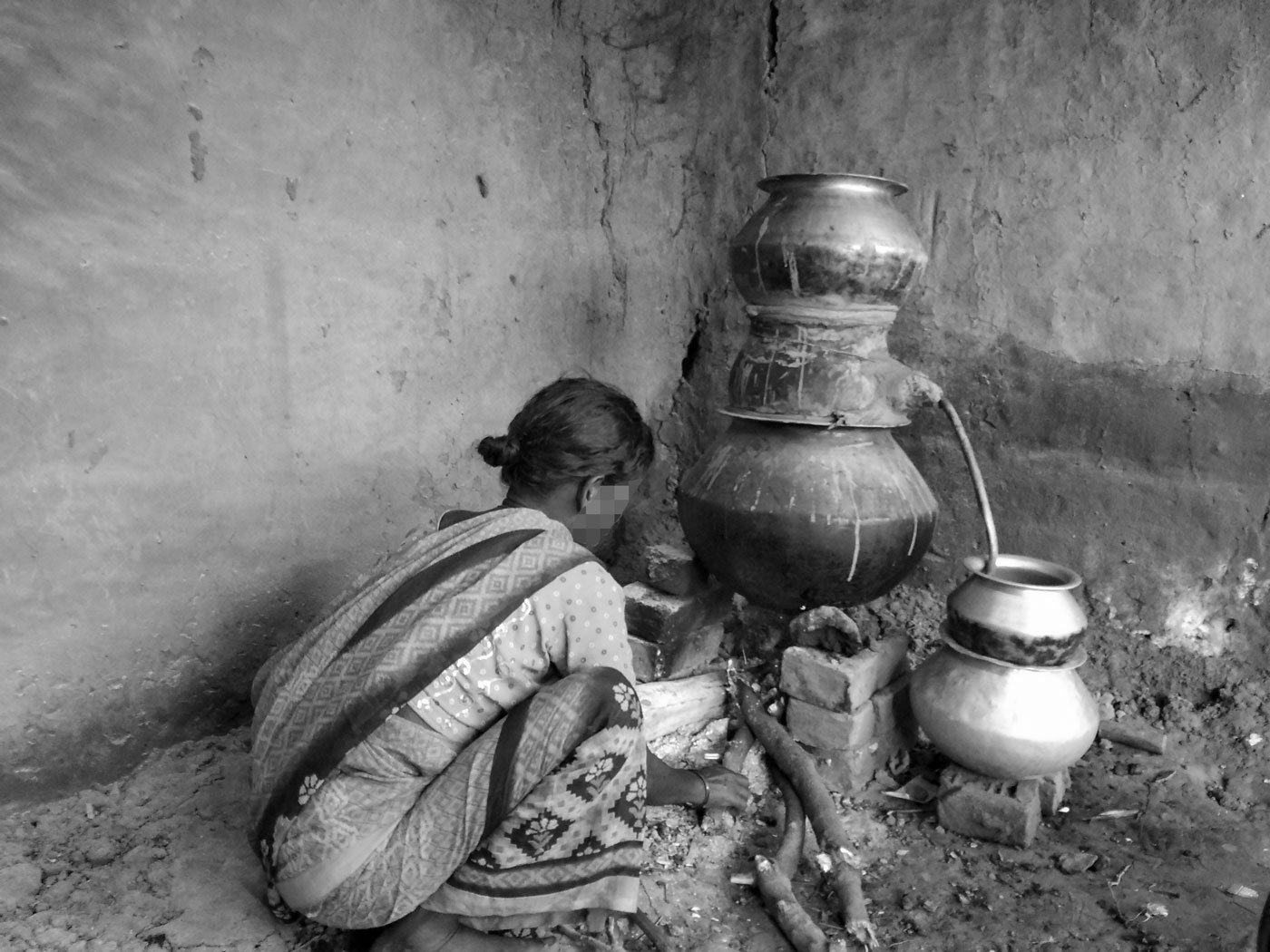

Alcohol distillation is a time-consuming process. First, the

mahua

flowers

are mixed with

gud

(jaggery)

and water,

and left soaking for eight days to ferment. The mixture is then moved to a metal

handi

(pot) that’s set on a

chulha

to boil. Another

handi

, which is smaller and made of clay, with an open bottom, is placed over the metal one. This clay

handi

has a hole where a pipe is fitted and another metal

handi

containing water is placed above it. The gaps between the three

handis

are filled in with mud and clothes to trap the vapour.

Left: A fermented mixture of

mahua

flowers, jaggery and water is boiled to produce vapour, which gets accumulated in the earthen pot in the middle. Right: The metal utensil connected to the pipe collects the dripping condensation. The distillation process is time-consuming

Muneshwar extracts 40 litres of mahua daaru in a month, for which he needs 7 kilos of flowers, 30 kilos of jaggery and 10 litres of water. He buys the flowers for Rs. 700 and jaggery for Rs. 1,200. He pays Rs. 80 for 10 kilos of wood to fire the stove. His monthly expense on the raw materials stands at Rs. 2,000.

“We earn Rs. 4,500 per month selling the liquor,” Muneshwar says. “After spending on food, we hardly manage to save 400-500 rupees. This money is spent on the children, who often ask for biscuits and toffees.” He and his wife, 36-year-old Chameli Devi, have three daughters between the ages of 5 and 16. Their youngest, a son, is 4 years old. Chameli also works as an agricultural labourer and makes alcohol with her husband .

Their customers are mainly labourers from nearby villages. “We charge Rs. 35 for 250 ml [of liquor],” says Muneshwar. “The customers have to pay in cash. We don’t entertain anyone who wants to have it on udhaar [credit].”

The demand for liquor is huge – eight litres sell in just three days. But making liquor in larger quantities is riskier. “When the police raids, they destroy all the liquor and we face loss,” Muneshwar adds. The ‘crime’ is punishable with imprisonment, which could be rigorous or extend to life, and hefty fines of one lakh to ten lakh rupees.

For Muneshwar, liquor is a means of survival and not a profit-making enterprise. “See my house, we have no money even to repair it,” he says, pointing to the one-room structure. He needs at least Rs. 40,000-50,000 to fix it up. The room has an earthen floor; the interior walls are layered with clay, and there is no window for ventilation. The chulha is at one end of the room, where the metal pot for rice and a kadai (pan) for pork meat are also kept. “We eat pork meat a lot. It is healthy for us,” says Muneshwar. Pigs are reared for meat in the tola , and the pork, sold at 3-4 shops in the tola , is priced at Rs. 150-200 a kilo, says Muneshwar. The vegetable market is 10 kilometres away. “We consume mahua daaru too sometimes,” he says.

The Covid-19 lockdowns in 2020 had little impact on liquor sales, and Muneshwar had managed to earn Rs. 3,500-4,000 a month in that period. “We arranged mahua , gud and prepared it,” he says. “There were not many restrictions in remote areas, so it helped us. We got customers too. Consumption of liquor is so common that people will have it at any cost.”

Left: Muneshwar Manjhi got his MGNREGA job card seven years ago, but he was never offered any work. Right: All the six members of his family sleep in the one-room home, which doesn't have any windows

Yet, he was pushed into debt when his father died in March 2021. To perform the last rites and arrange a community meal, as is the custom, Muneshwar had to borrow Rs. 20,000 on five per cent interest per month from a private moneylender of the Rajput caste. “If there was no liquor ban, I would have saved enough money [by making more] and repaid the loan,” he says. “I have to take out a loan if anyone falls ill. How can we survive this way?”

In the past, Muneshwar had migrated to other states for better job opportunities only to return disappointed. He first went to Pune in Maharashtra in 2016, to work on construction projects, but came back home in three months. “The contractor who had taken me there was not giving me work. So I got frustrated and left,” he says. In 2018, he went to Uttar Pradesh, and returned in a month this time. “I was getting only Rs. 6,000 a month to dig up roads, so I came back,” he says. “I haven’t gone anywhere since then.”

State welfare policies haven’t made inroads in the Musahari tola . No measures have been taken for job creation, but the mukhiya (chief) of the gram panchayat that administers the tola has been urging the locality’s residents to stop making liquor. “The sarkar [government] has abandoned us,” says Muneshwar. “We are helpless. Please go to the sarkar and tell them that you didn’t see a single toilet in the tola . The government is not helping us, so we have to make alcohol. If the government gave us alternative jobs or money to start a small shop or to sell meat- machhli [fish], then we would not have continued the liquor business.”

For Motilal Kumar, a 21-year-old resident of the Musahari tola , mahua daaru is the main source of income now. He had started distilling the alcoholic spirit 2-3 months before the ban in 2016 because of irregular agricultural work and low wages. “We were given just five kilos of rice as our daily wage.” In 2020, he says, he got only two months of farm work.

Left: Motilal Kumar’s mother Koeli Devi checking the stove to ensure the flames reach the

handi

properly.

The entire family works to distil the

mahua daaru

.

Right: Motilal and Koeli Devi in front of their house in the Musahari

tola

Motilal, his mother Koeli Devi, 51, and his wife Bulaki Devi, 20, are all involved in making mahua daaru . They distil about 24 litres every month. “Whatever money I earn by brewing the spirit is spent on food, clothes and medicines,” he says. “We are very poor. Even after making the alcohol we are unable to save money. I am somehow taking care of my daughter Anu. If I make more [liquor], my income will increase. For that, I need money [capital], which I don’t have.”

The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee (MGNREGA) programme has not been of much help to the Musahars here. Though Muneshwar had got an MGNREGA card made seven years ago, he was never offered any work. Motilal has neither an MGNREGA nor Aadhaar card. Many residents in the tola find obtaining an Aadhaar card to be a taxing bureaucratic procedure. “When we visit the block office [three kilometres away], they ask for a letter from the mukhiya with his signature. When we give them the mukhiya ’s letter, they ask for a letter from the school. When I produce a school letter, they ask for money,” Motilal says. “I know that the block officials give Aadhaar cards after taking bribes of 2,000 to 3,000 rupees. But I have no money.”

Living conditions in the Musahari tola are clearly inadequate. There are no toilets, not even a community toilet. No household has an LPG connection – people still use wood to cook and make alcohol. And though the closest primary health centre is three kilometres away, it serves more than a dozen panchayats . “Treatment facilities are poor, so people depend on private clinics,” the mukhiya says. According to the residents, not even one Covid-19 vaccination camp was organised in the tola during the pandemic. No government healthcare official visited the area to create awareness.

In the absence of even the basic amenities, it was liquor sales that kept families in the tola afloat. “We don’t get jobs anywhere, so we do it [make liquor] out of majboori [compulsion],” says Motilal. “We are surviving on the liquor only. If we stop making it, we will die.”

Names of the people and their exact location have been changed in the story to protect the identity of individuals.