“My abbu [father] was a wage worker, but fishing was the love of his life. He would somehow manage the money for a kilogram of rice and then… he was gone for the day! My ammi [mother] had to deal with everything else,” says Kohinoor Begum, speaking on the terrace of her home in Beldanga’s Uttarpara locality.

“And imagine, out of that one kilo of rice, my ammi had to feed four children, our dadi [paternal grandmother], my father, an aunt and herself.” She pauses briefly and then says, “On top of that, abbu had the courage to ask her for some rice to bait fish. We were at our wit’s end with this man!”

Kohinoor aapa [sister], 55, is a mid-day meal cook at Janaki Nagar Prathamik Vidyalaya Primary School here in Bengal’s Murshidabad district. In her spare time, she rolls beedis and also campaigns for the rights of other women engaged in this work. In Murshidabad, it is the poorest of women who roll beedis — a physically punishing job. The constant exposure to tobacco from a young age puts their health at great risk too. Read: Women beedi workers’ health: up in smoke

On a December morning in 2021, Kohinoor aapa met this reporter after attending a campaign for beedi workers. Later, a more relaxed Kohinoor spoke about her childhood and even sang her own composition – a song on the arduous work and exploitative working conditions of beedi workers.

When she was a child, Kohinoor aapa said her family’s dire financial situation caused a lot of unpleasantness at home. The young girl found it unbearable. “I was only nine,” she says when, “one morning, amidst the usual chaos at home, I found my ammi sobbing while preparing the earthen chulha with coal, cow dung cakes and wood. She had no grains left to cook.”

Left: Kohinoor Begum with her mother whose struggle inspired her to fight for one’s own place in society. Right: Kohinoor leading a rally in Berhampore, Murshidabad, December 2022. Photo courtesy: Nashima Khatun

An idea struck the nine-year-old. “I ran to meet the wife of a big coal depot owner and asked the lady, ‘কাকিমা, আমাকে এক মণ করে কয়লা দেবে রোজ? [ kakima amake ek mon kore koyla debe roj? ‘Aunt, will you give me a mound of coal every day?’],” she recollects with pride. “After some persuasion, the lady agreed and I started bringing coal from their depot to our home on a rickshaw. I spent 20 paisa on the fare.”

Life continued in this way and by the time she was 14, Kohinoor was selling scrap coal in her village of Uttarpara and other close by localities; she would carry up to 20 kgs at a time on her young shoulders. “Even though I could earn very little, it helped my family with our meals,” she says.

Although happy and relieved that she could help out, Kohinoor felt she was losing out on life. “While selling coal on the road, I would notice girls going to school and women to colleges and offices with bags on their shoulders. I felt sorry for myself,” she says. Her voice starts to get heavy but she pushes back the tears and adds, “I too was meant to go somewhere with a bag on my shoulder…”

At around that time, a cousin introduced Kohinoor to local self-help groups for women, organised by the municipality. “While selling coal to various houses, I met so many women. I knew their hardships. I insisted that the municipality take me as one of the organisers.”

The problem however, as raised by her cousin, was that Kohinoor lacked formal schooling and was therefore considered unsuitable for the job that involved managing the accounting books.

“This was hardly an issue for me,” she says, “‘I am very good with counting and calculations. I learnt it while selling scrap coal.” Assuring them that she wouldn’t make mistakes, Kohinoor said her only request was that she get help from her cousin to put everything down in the diary. “I will manage the rest.”

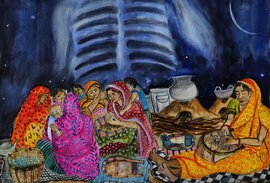

Left: Kohinoor aapa interacting with beedi workers in her home. Right: With beedi workers on the terrace of her home in Uttarpara village

And so she did. Working for local self-help groups gave Kohinoor the chance to get to know most of these women better — many of whom were beedi rollers. She learnt about saving, creating a corpus, borrowing from it and repaying as well.

Although money continued to be a struggle for Kohinoor, she says the work on the ground became “valuable experience” because “I was becoming politically aware. I was always arguing with people if I saw something was wrong. I forged close ties with trade union activists.”

This however did not sit well with her family and relatives. “So, they got me married.” At 16, she was married to Jamaluddin Sheikh. The couple have three children.

Fortunately marriage did not stop Kohinoor aapa from doing the work she liked: “I kept observing everything around me. I admired grassroot organisations that worked for the rights of women like me and my association with them kept growing.” While Jamaluddin works as a plastic and waste collector, Kohinoor keeps busy with work at school and with the Murshidabad District Beedi Mazdur and Packers Union, where she advocates for rights of beedi -rollers.

“Only on Sunday mornings, I manage to get some time,” she says as she pours some coconut oil from a bottle next to her onto her palm. She applies the oil on her thick hair and then combs it carefully.

When she is done, Kohinoor covers her head with a dupatta and looks at the tiny mirror in front of her, “[I feel like singing songs today] একটা বিড়ি বাঁধাইয়ের গান শোনাই… Ekta beedi-bandhai-er gaan shonai [Let me sing a song on beedi rolling…].”

বাংলা

একি ভাই রে ভাই

আমরা বিড়ির গান গাই

একি ভাই রে ভাই

আমরা বিড়ির গান গাই

শ্রমিকরা দল গুছিয়ে

শ্রমিকরা দল গুছিয়ে

মিনশির কাছে বিড়ির পাতা আনতে যাই

একি ভাই রে ভাই

আমরা বিড়ির গান গাই

একি ভাই রে ভাই

আমরা বিড়ির গান গাই

পাতাটা আনার পরে

পাতাটা আনার পরে

কাটার পর্বে যাই রে যাই

একি ভাই রে ভাই

আমরা বিড়ির গান গাই

একি ভাই রে ভাই

আমরা বিড়ির গান গাই

বিড়িটা কাটার পরে

পাতাটা কাটার পরে

বাঁধার পর্বে যাই রে যাই

একি ভাই রে ভাই

আমরা বিড়ির গান গাই

ওকি ভাই রে ভাই

আমরা বিড়ির গান গাই

বিড়িটা বাঁধার পরে

বিড়িটা বাঁধার পরে

গাড্ডির পর্বে যাই রে যাই

একি ভাই রে ভাই

আমরা বিড়ির গান গাই

একি ভাই রে ভাই

আমরা বিড়ির গান গাই

গাড্ডিটা করার পরে

গাড্ডিটা করার পরে

ঝুড়ি সাজাই রে সাজাই

একি ভাই রে ভাই

আমরা বিড়ির গান গাই

একি ভাই রে ভাই

আমরা বিড়ির গান গাই

ঝুড়িটা সাজার পরে

ঝুড়িটা সাজার পরে

মিনশির কাছে দিতে যাই

একি ভাই রে ভাই

আমরা বিড়ির গান গাই

একি ভাই রে ভাই

আমরা বিড়ির গান গাই

মিনশির কাছে লিয়ে যেয়ে

মিনশির কাছে লিয়ে যেয়ে

গুনতি লাগাই রে লাগাই

একি ভাই রে ভাই

আমরা বিড়ির গান গাই

একি ভাই রে ভাই

আমরা বিড়ির গান গাই

বিড়িটা গোনার পরে

বিড়িটা গোনার পরে

ডাইরি সারাই রে সারাই

একি ভাই রে ভাই

আমরা বিড়ির গান গাই

একি ভাই রে ভাই

আমরা বিড়ির গান গাই

ডাইরিটা সারার পরে

ডাইরিটা সারার পরে

দুশো চুয়ান্ন টাকা মজুরি চাই

একি ভাই রে ভাই

দুশো চুয়ান্ন টাকা চাই

একি ভাই রে ভাই

দুশো চুয়ান্ন টাকা চাই

একি মিনশি ভাই

দুশো চুয়ান্ন টাকা চাই।

English

Listen o brother

Here we chime

This song of the beedi

Listen to us rhyme.

The labourers gather

The labourers gather

We go to the munshi [middleman], beedi-leaves to bring.

Listen o brother

Here we sing,

This song of the beedi

Listen to us sing.

The leaves we bring back

The leaves we bring back

And set about for a round o' cutting.

Listen o brother

Here we sing,

This song of the beedi

Listen to us sing.

Once the beedis are cut

Once the leaves are cut

We prepare for the final rolling.

Listen o brother

Here we sing,

This song of the beedi

Listen to us sing.

After the beedis are rolled

After the beedis are rolled

We begin the stage of bundling.

Listen o brother

Here we sing,

This song of the beedi

Listen to us sing.

Once the gaddis [bundles] are done

Once the bundles are done

Our baskets we start packing.

Listen o brother

Here we sing,

This song of the beedi

Listen to us sing.

Now the jhuris [baskets] are packed

Now the baskets are stacked

To the munshi we start carrying.

Listen o brother

Here we sing,

This song of the beedi

Listen to us sing.

Once at the munshi's place

Once at the munshi's place

We set upon the final tallying.

Listen o brother

Here we sing,

This song of the beedi

Listen to us sing.

Now the tallies are over

Now the tallies are over

Out comes the diary, we start scribbling.

Listen o brother

Here we sing,

This song of the beedi

Listen to us sing.

The diary has been filled

Pay our wages and listen to us chant.

Listen o brother

For our wages, we chant.

Twice a hundred and fifty-four in change,

Hear o munshi, please do arrange.

Two fifty-four bucks, that's all we need,

Listen o munshi, listen indeed.

Song credits:

Bengali song: Kohinoor Begum

English translation: Joshua Bodhinetra